Blinken Draws Fire Over Afghanistan Blame Game, “Stonewalling”

Former Ambassador Thomas Boyatt, a highly decorated foreign service officer who served in multiple senior U.S. foreign service roles in the 1970s and 80s, has a bone to pick with Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Since the chaotic and deadly U.S. exit from Afghanistan, Blinken has refused to turn over to Congress a key internal State Department dissent document signed by 23 U.S. diplomats at the embassy in Kabul. The classified cable was sent to Blinken and top leadership at State in July 2021, one month before the evacuation descended into chaos. The classified memo reportedly urged the administration to accelerate evacuation plans because the Afghan government was on the brink of collapse as the Taliban swept the country. Its existence was leaked to the Wall Street Journal after the Taliban took control of the country and the U.S. withdrawal quickly went sideways.

What’s worse, in Boyatt’s view, is that the State Department is now using a misleading precedent surrounding a dissent cable he sent nearly 50 years ago as its rationale for withholding the Afghanistan dissent document from Congress.

When Boyatt learned about Blinken’s refusal and his reasons – that he was trying to protect future dissent cables from a chilling effect – “It was like tearing off the scab of an old wound of mine,” Boyatt, now 90, told RealClearPolitics Tuesday.

Blinken had cited the 1975 precedent of the department’s refusal to provide Congress the dissent cable written by Boyatt before Turkey invaded Cyprus just a year before. Boyatt recently provided a statement to Rep. Mike McCaul, slamming Blinken’s stated concerns about protecting the integrity of the dissent cable system as “bullshit.”

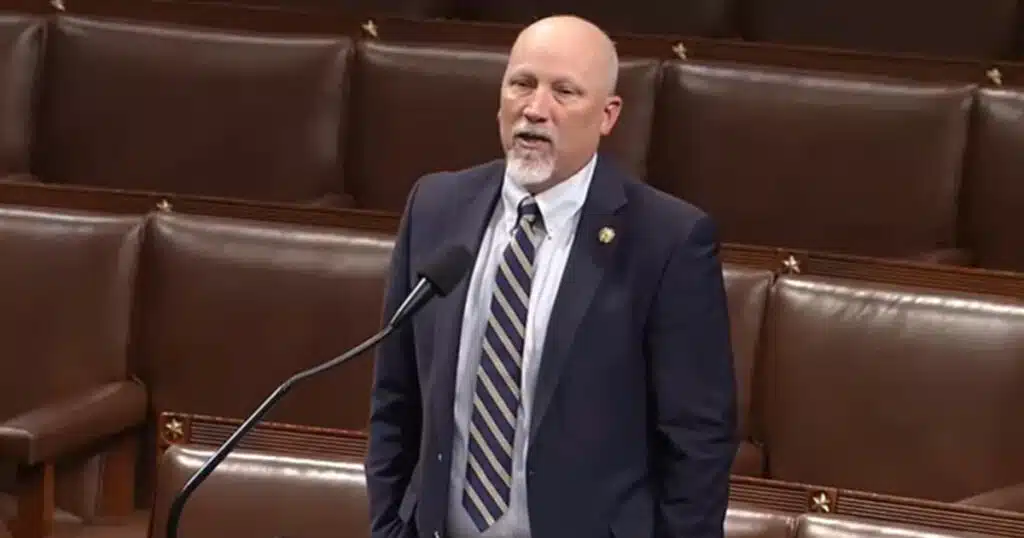

McCaul, a Texas Republican who now chairs the House Foreign Affairs Committee, has been requesting the cable since first learning about it in late August of 2021 while events were unraveling in Kabul. Last week, a deadline passed for McCaul’s subpoena for the cable, with Blinken still resisting.

While serving as the State Department’s director for Cyprus affairs, Boyatt used the official dissent channel to warn then-Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and the Nixon administration that the Greek army was planning to overthrow the Cypriot president and install a puppet Cypriot government. If this were to occur, his cable warned, Turkey’s armed forces would invade Cyprus and establish a Turk-Cypriot mini-state on Cyprus, leading to the displacement of Cyprus’s ethnic communities and fueling Turkey’s expansionist objectives. Boyatt says he decided to utilize the dissent cable process to alert the Nixon administration about the impending invasion after exhausting normal State Department channels.

Instead of attempting to stop the invasion, however, Kissinger removed Boyatt from his position in Cyprus five days after he sent the cable. Boyatt went on to serve as counselor in the U.S. embassy in Chile while events in Cyprus unfolded just as he had warned.

Boyatt notes that his friend, Rodger Davies, who was serving as ambassador to Cyprus at the time, was shot dead during a Greek Cypriot protest outside the U.S. embassy. It was just a week after Turkey’s invasion, and roughly 300 people were protesting against the United States’ failure to prevent the Turkish invasion.

After the Nixon administration, Boyatt served as ambassador to Upper Volta in 1978 and ambassador to Colombia in 1980. Even before Kissinger punished him for airing opposition through the classified dissent cable process, Boyatt was already a hero within the agency – lauded for his bravery demonstrated during a 1969 TWA flight he was on that was hijacked by Palestinian terrorists. That year, the State Department honored him with its Meritorious Honor Award for helping injured passengers to safety and negotiating the passengers’ release with the Syrian government.

Roughly a year after Turkey invaded Cyprus, a Democratic-controlled House committee decided to scrutinize the Nixon administration’s foreign policies in Cambodia, Chile, and Cyprus. It demanded that Kissinger hand over Boyatt’s dissent cable on Cyprus. Kissinger refused, arguing that he wanted to protect Boyatt from retaliation.

“That was a joke at the time,” Boyatt recalled, explaining that back then, “everybody in my world” was well aware of Kissinger’s penchant for punishing those who challenged his judgment and the administration’s prevailing foreign policies.

State Department officials across the agency were on edge because Kissinger had recently retaliated against another U.S. diplomat, Archer Blood, for sending what was considered one of the most strongly worded cables in the history of the U.S. foreign service while serving as U.S. consul general to Dhaka, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Signed by 20 members of the diplomatic staff. the “Blood Telegram” protested the atrocities being committed in the Bangladesh Liberation War.

The dissent memo angered Kissinger, who recalled Blood from the position and assigned him to the State Department personnel office, retribution for airing his views contradicting Kissinger’s and Nixon’s hopes of using the support of West Pakistan for diplomatic openings with China.

Even though the demotion severely harmed Blood’s career, his telegram became the precursor to the creation of the official State Department “dissent channel” that formed in the following years, the same system Boyatt used to air his warnings. The State Department agreed to establish the channel partly in response to concerns that contrary opinions were suppressed or ignored during the Vietnam War. In 1971, Blood received a prestigious Christian Herter Award for “extraordinary accomplishment involving initiative, integrity, intellectual courage, and creative dissent.” The Herter Award was established by the American Foreign Service Association, AFSA, the U.S. foreign service labor union, to honor senior diplomats who challenge the status quo.

“The point is that nobody in Washington or the State Department or anyone else believed that Kissinger’s concern was for the well-being of the dissenters,” Boyatt recalled. “His concern was that he did not want a series of mistakes in the public record with respect to the Cyprus crisis. I strongly suspect that that is the same motive with Blinken.”

The State Department has vigorously defended its decision to fight McCaul’s subpoena. The agency also denied a request for the cable by Rep. Gregory Meeks, a New York Democrat who chaired the panel before Republicans won the majority last year.

Instead, State has offered to provide a closed-door briefing, proposed for later this week, for McCaul and other members of Congress about the “concerns raised and the challenges identified” by U.S. embassy staff in Kabul before and during the withdrawal, State Department spokesperson Vedant Patel told RCP.

“Secretary Blinken has continued to make clear his and the State Department’s commitment to working with the House Foreign Affairs committee to provide relevant information while also upholding his responsibility to protect the integrity of the Department’s dissent channel,” Patel said in an emailed statement. “We continue to believe that our offers can satisfactorily provide the committee with the information it needs to conduct its oversight function while still protecting the dissent channel.”

McCaul has repeatedly dismissed Blinken’s justification for withholding the Afghanistan dissent cable and has pledged to pursue legal recourse if Blinken continues to ignore his subpoena. While McCaul has accepted State’s offer for a briefing, he has told the agency that it in no way satisfies the subpoena.

“I am currently discussing next steps with my staff and House legal counsels to decide on what action to take if the State Department continues to refuse to comply with the subpoena despite their legal obligation to do so,” McCaul said in a statement last week.

Boyatt also rejects the State Department’s rationale that it’s simply protecting dissenters from retaliation and trying to prevent a chilling effect on future dissent.

“The reality is that if a dissent cable or dissent memorandum for one reason or another reaches public purview, it’s good for a variety of national security reasons because it forces the bureaucracy to confront its mistakes and to concentrate on not repeating them,” Boyatt said.

The dissenters themselves are applauded by their peers, Boyatt said, and rightly so because all foreign service officers take an oath to support and defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic, and to do their best to support U.S. foreign policy interests.

“They instantly become heroes to some 15,000 foreign service officers serving all over the world,” he added. “They become eligible for, and many do receive, awards from the American Foreign Service Association for creative dissent.”

Underscoring his point, two diplomats stationed in Kabul who signed the July 2021 dissent cable recently received AFSA’s William R. Rivkin Award for Constructive Dissent by a Mid-Level Foreign Service Officer. The union publicly recognized the pair for their “courage” in using the classified dissent channel to “speak an unpopular truth to power.”

Elisabeth Zenos and Anton Cooper, foreign service officers who served in Kabul in 2020 and 2021, embody “the best traditions of the Foreign Service and constructive dissent in a uniquely difficult moment, bringing their intellectual courage, astute analysis and willingness to speak an unpopular truth to power,” AFSA wrote about the pair on its website.

“Using the appropriate internal embassy channels, Ms. Zentos and Mr. Cooper presented their concerns and a proposed course of action,” the organization said, adding that Zentos and Cooper turned to the dissent channel when their positions differed from the “established views of decision-makers.”

AFSA also noted that the cable received the “required response from the secretary of state’s policy planning staff, and preparations reportedly sped up – but unfortunately, not quickly enough to avoid the events that transpired in Kabul.”

Despite choosing Zentos and Cooper for the award, one of several the union handed out in 2022, AFSA has defended Blinken’s decision to withhold the dissent cable from Congress. In March, Eric Rubin, the union’s president, said the dissent channel must be protected under the executive branch or risk undermining the privileged purposes the secure communication line provides.

“AFSA maintains that constructive dissent can only thrive and be successful if it remains confidential and confined to internal discussion within the executive branch,” Rubin said in the statement.

Boyatt strongly disagrees and says he’s hardly alone among his State Department colleagues, current and retired. “I think they’re wrong, and the next time I see [Rubin], the current president, I’m going to tell him that,” Boyatt told RCP.

Republicans over the last week have hammered the Biden administration for what they characterized as more than a year of stonewalling their oversight requests for key Afghanistan documents. McCaul on Tuesday sent a separate letter to Blinken asking for the public release of key parts of its after-action review of the Afghanistan withdrawal. The Texas Republican stressed that some of the information in the report that he’s reviewed “stands directly at odds with the administration’s public narratives.”

The 87-page report was completed more than a year ago and was only provided to Congress recently after a subpoena threat from Republicans. McCaul also took issue with State’s decision to withhold parts of the after-action review from the public even though the vast majority of its contents are marked as either “sensitive but unclassified” or “unclassified.” The unclassified sections of the review, including the executive summary, findings, and recommendations, should be released “immediately,” and an unclassified version of the complete document within 60 days, McCaul argued.

State Department spokesman Vedant Patel on Tuesday said there are “no plans” at the moment to declassify the after-action review and release it publicly.

On April 6, while Congress was out of town and two days before Easter weekend, the Biden administration released a 12-page unclassified document claiming to summarize the findings of the after-action review. John Kirby, the National Security Council spokesman, released the summary 10 minutes before appearing at a White House press conference. The move drew criticism from several reporters who publicly complained of being blind-sided by the report.

While the summary acknowledged mistakes in evaluating the risks of a Taliban takeover of the Afghan government, the Biden administration defended its decision to end the war and blamed the Trump administration for leaving them with few options and even less planning capability.

When RealClearPolitics’ Phil Wegmann asked if the after-action review summary included information about the dissent cable, Kirby referred him to the State Department. During the briefing, reporters also repeatedly questioned Kirby for denying that the Afghanistan evacuation was chaotic despite disturbing photos and videos that emerged amid the final days of the withdrawal.

“For all this talk of chaos, I just didn’t see it,” Kirby told reporters during the White House briefing, adding, “I just don’t buy the whole argument of chaos.”

The shocking images from the final days of the Afghanistan withdrawal showed desperate Afghans clinging to the wings and wheels of U.S. military planes taking off from Kabul, including images of several Afghans falling to their deaths. On August 26, a suicide bomber killed 13 U.S. servicemen and women, injured 45 others, and killed 170 Afghans after the Taliban took control of the country and panicked Afghans, along with U.S. citizens, jammed into the Kabul airport in a desperate attempt to flee.

Last month, Sgt. Tyler Vargas-Andrews, a Marine sniper, told a House hearing convened by McCaul that his military leaders ignored his warnings about the suicide bomber’s movements. Several minutes later, the bomber detonated his vest in a blast that cost Vargas-Andrews a leg, an arm, and a kidney. Vargas-Andrews has undergone 44 surgeries over the last year and a half.

After the Biden administration released the 12-page summary report, a former U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan called the document “shameful” and “a White House whitewash.”

Retired Ambassador Ryan Crocker, who capped a four-decade foreign service career as the top U.S. diplomat in Kabul in 2011 and 2012, said the Trump administration bears blame for adhering to a pre-determined end date for the exit of U.S. and NATO forces, but that doesn’t absolve Biden for carrying out the Trump policy without setting conditions or considering shifting dynamics on the ground.

“Frankly, it’s dishonest,” Crocker said of the Biden administration’s repeated blaming of Trump and his senior foreign policy leaders. “This administration – ably and amply assisted by the previous administration, of course – were the ones who set the stage for that incredibly swift Taliban takeover.”

Crocker also blasted the summary for touting the Biden administration’s work to ramp up the processing of special immigrant visas for Afghans who aided Americans as interpreters and in other roles that makes them Taliban targets while failing to mention that hundreds of thousands of Afghan allies are still trying to flee the country.

The absence of any mention of our broken promises to Afghan allies is “as shameful and as egregious to me as anything in that document,” Crocker said. More than 150,000 special immigrant visa applicants are still trying to escape Afghanistan, according to internal Biden administration estimates, Foreign Policy reported in March. Other advocates say the numbers could be twice as high.

Crocker says he believes Blinken should provide the dissent cable to Congress without the names of those who signed it to protect their identities and prevent any possible harm to their careers “down the line,” especially when it comes to younger foreign service officers.

“I certainly believe that with an issue of this magnitude, Congress has an obligation to seek, and the executive has an obligation to provide, access to reports that have a direct bearing on a huge foreign-policy issue,” he told RCP.

It was appropriate to keep the document classified in the weeks after it was first generated amid a quickly deteriorating situation in Afghanistan, Crocker said, but those reasons no longer apply.

“That’s not what you would want to have out on the street available to our adversaries in the middle of this whole thing, but my guess is now that we are way, way past that … the classification has to be re-looked in light of the current situation,” he said.

Crocker also has a personal experience of voicing dissent, although there was no time to put his views into writing or to get a cable out. In the fall of 1983, several months after the deadly bombing of the U.S. embassy in Beirut, Crocker said the Reagan White House envoy for Lebanon, Robert “Bud” McFarlane, “got himself panicked by a Lebanese brigade commander that the forces of darkness were sweeping all the forests and unless we did something, they would have seized the presidential palace complex within a matter of hours.”

Crocker said he received a call from David Mack, a former ambassador to the United Arab Emirates who was serving as the director of Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan back at the State Department at the time. Mack told him what the recommendation was and asked for his thoughts.

“I thought it was a catastrophic mistake, and then dictated to him over a secure phone my opposition to it and why – [That it was] essentially dragging us as a participant into the Lebanese civil war,” Crocker recalled. “Like most messages, it was basically ignored.”

McFarlane has been criticized for his decision to order the USS New Jersey to bombard Lebanese opposition forces, which may have led to the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing where 241 U.S. servicemen, 58 French military personnel, and six civilians were killed. After that assignment, McFarlane returned to Washington and became President Reagan’s national security adviser and a central figure in the Iran-Contra affair.

A year or so later after formally objecting, Crocker received an award by AFSA for creative dissent for choosing to voice his opposition to the prevailing foreign policy opinion.

“Again, it had no impact whatsoever, but I would have been perfectly fine if that message was released or the transcription was released and my name was attached to it,” he said. “It would not have bothered me in the slightest. I would have been happy.”

The White House also has tried to defend itself against searing criticism from Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction John Sopko, who accused the administration last week of unprecedented obstruction of his oversight of the chaotic withdrawal from Kabul.

The morning before Sopko testified to the House Oversight Committee, the administration, in a memo to reporters, argued that it had provided “thousands of pages of documents, analyses, spreadsheets, and written responses to questions, as well as hundreds of briefings to bipartisan members and staff and public congressional testimony by senior officials, all while consistently providing updates and information to numerous inspectors general.”

White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre repeated the claim in tense exchanges with reporters during her daily briefing. There was no mention, however, of Blinken’s refusal to provide a copy of the dissent cable.

This article was originally published by RealClearPolitics and made available via RealClearWire.