What If 1 Day the Federal Workforce Just Disappeared? Turns Out, It Has

As of Wednesday, it’s been 1,143 days since workers across the country were sent home in an effort to slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus. It’s been 692 days since the Biden administration issued a plan for “an effective, orderly, and safe increased return of Federal employees and contractors to the physical workplace” and 227days since President Joe Biden declared that “the pandemic is over.”

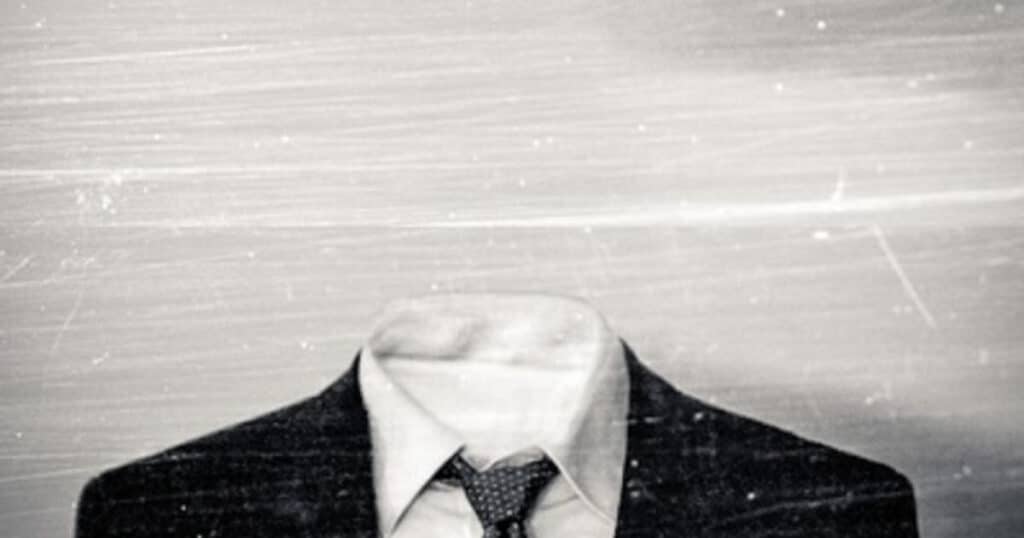

But enter any federal agency’s office building in downtown Washington, and you’re likely to find a skeleton workforce, reminiscent of the early months of the pandemic.

Remote work and flexibility can be a win-win for certain businesses and workers, but only under certain conditions.

Not all jobs can be done remotely. Some require a combination of remote and in-person work, and most remote work necessitates flexibility to respond to changing needs.

That’s why the attempts by unions for federal employees to impose one-size-fits-all remote work policies across entire agencies are so problematic.

Take the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, for example. While the American Federation of Government Employees is trying to finalize a permanent telework program, employees are required to come in to work only four times during each two-week pay period.

If that policy becomes permanent, will the aggrieved workers whom the EEOC serves have access to in-person representation only two days a week? The federal government can’t operate effectively if federal employees have the right to refuse to show up in person when needed.

That seems to be a problem currently, as the government’s effectiveness reached an all-time low for serving veterans, processing tax returns, approving passport applications, and other services.

The other key component of productive remote work policies is accountability. But accountability is anathema in the federal workforce.

According to a study by the Office of Personnel Management, almost 80% of all federal managers say they have managed a poorly performing employee, but fewer than 15% issued less than fully successful ratings for problematic employees and only 8% attempted to reassign, demote, or remove problematic employees. Of the mere 8% who attempted to impose accountability, fully 78% said their efforts had no effect.

Some lawmakers who are paying attention have tried either to restrict or end this practice. In 2021, for example, Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., urged “immediate action to transition federal workers to resume in-person operations.”

The latest effort, a bill introduced in January by Rep. James Comer, R-Ky., has passed the House and been sent to the Senate, where it awaits a likely early death at the hands of Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y.

Comer’s “SHOW UP Act” (using an acronym for Stopping Home Office Work’s Unproductive Problems) would prevent the Biden administration from cementing outdated telework policies until Congress is supplied with a reasonable plan to avoid the negative effects of telework and require federal agencies to study those effects on each agency’s mission.

And it’s not just senators and congressmen who have flagged this need to return to normality. Even Biden has agreed that federal workers should return to the office to restore downtown traffic and commerce in the nation’s capital. The problem is that the president’s plan is just that—a plan to require agencies to produce plans, with zero consequence for not following through with those plans.

Note that many in the private sector have moved past mass telework policies. Among those, Elon Musk has led the charge by requiring Tesla employees to spend 40 hours a week in the office or resign. Other large companies insisting on in-person office work include Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, and Netflix.

It seems as if the COVID-19 pandemic is over for everyone but for federal workers in Washington, D.C.

Officials have wasted taxpayers’ money on paying for inefficient telework and mostly empty office buildings in the nation’s capital, about a third of which are leased by the federal government.

The most intense defense of telework comes from labor unions, which have succeeded in introducing remote work policies in federal employee union agreements, making it increasingly difficult for agencies to require employees to return to the office.

There is no denying that federal agencies are falling short of their missions. It is the duty of government employees to serve the taxpayers, not themselves.

Until federal government ends its mass telework policies, the government will continue to let the American people down.