When a Judge Says a ‘2 Genders’ T-Shirt Makes Others Feel ‘Unsafe’

Score one for the woke scolds, who now get to dictate what kinds of messages nonwoke students are permitted to express in school.

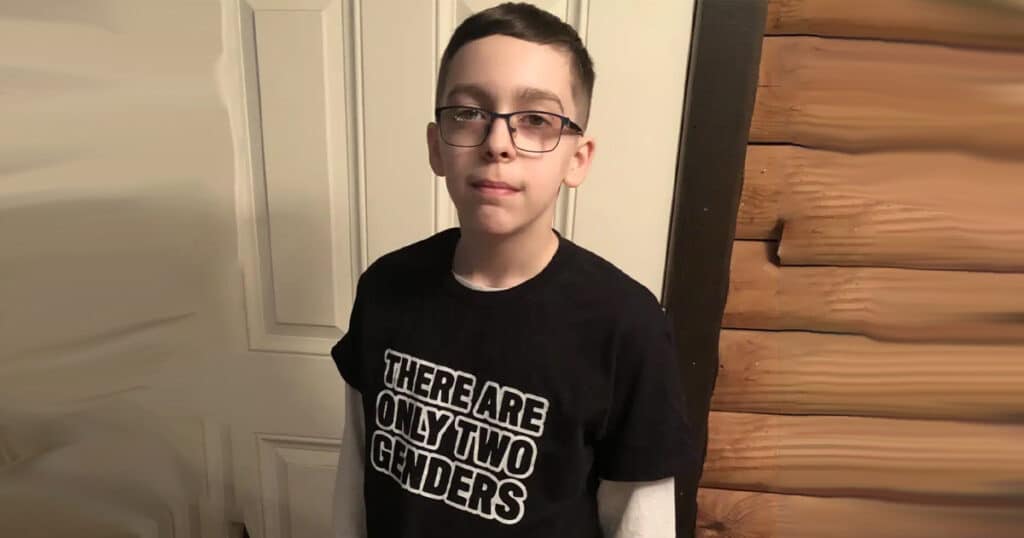

Liam Morrison, a 12-year-old from Massachusetts, was sent home from school for wearing a T-shirt declaring in all capital letters: “THERE ARE ONLY TWO GENDERS.”

The reason? Liam was told that his shirt made other students feel “unsafe.”

Several months later, federal trial judge ruled that the school likely was within its rights to do so.

Liam’s attorneys at the public interest law firm Alliance Defending Freedom requested that the court prevent Nichols Middle School from prohibiting him from wearing such shirts to school while the case proceeds.

Liam’s lawyers claim that school officials’ censorship of his message and the school speech policy on which that censorship was based violate the First and 14th amendments to the U.S. Constitution as a form of viewpoint discrimination.

“This isn’t about a T-shirt; this is about a public school telling a seventh grader that he isn’t allowed to hold a view that differs from the school’s preferred orthodoxy,” ADF Senior Counsel Tyson Langhofer said. “Public school officials can’t censor Liam’s speech by forcing him to remove a shirt that states a scientific fact. Doing so is a gross violation of the First Amendment.”

Judge Indira Talwani, however, concluded June 16 in L.M. v. Town of Middleborough that wearing such a shirt would infringe upon other “students’ rights to be ‘secure and to be let alone’ during the school day.”

In doing so, Talwani, appointed by President Barack Obama, may have engaged in some acrobatic judicial interpretation.

Two cases help provide an understanding of how student speech is regulated in public schools.

In West Virginia v. Barnette (1943), the Supreme Court ruled that symbolic speech is protected within the free speech clause of the First Amendment, and that requiring all public school students to salute the American flag regardless of their individual moral or religious objections violated the First Amendment.

Some years later, in Tinker v. Des Moines School District (1969), the Supreme Court extended and further clarified speech protections for students. In that case, the high court famously wrote that neither students nor teachers “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

In Tinker, the Supreme Court found that the school administration unconstitutionally restricted the speech rights of students who wanted to wear black arm bands in protest of the Vietnam War.

The court also held that school officials could prohibit student speech only if the speech was likely to disrupt the learning environment, stating that speech that “materially disrupts classwork or involves substantial disorder or invasion of the rights of others is, of course, not immunized by the constitutional guarantee of freedom of speech.”

In the case at hand, Talwani acknowledged the Tinker case, but in her opinion and order denying Liam’s request to prevent his school from censoring his symbolic speech, she wrote:

Plaintiff … is unable to counter Defendants’ showing that enforcement of the Dress Code was undertaken to protect the invasion of the rights of other students to a safe and secure educational environment. School administrators were well within their discretion to conclude that the statement ‘THERE ARE ONLY TWO GENDERS’ may communicate that only two gender identities—male and female—are valid, and any others are invalid or nonexistent, and to conclude that students who identify differently, whether they do so openly or not, have a right to attend school without being confronted by messages attacking their identities. As Tinker explained, schools can prohibit speech that is in ‘collision with the rights of others to be secure and be let alone.’

Importantly, the portion of the Tinker opinion from which Talwani pulls that last sentence reads in full:

The school officials banned and sought to punish petitioners for a silent, passive expression of opinion, unaccompanied by any disorder or disturbance on the part of petitioners. There is here no evidence whatever of petitioners’ interference, actual or nascent, with the schools’ work or of collision with the rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone. Accordingly, this case does not concern speech or action that intrudes upon the work of the schools or the rights of other students.

Liam—in protest of the nation’s growing obsession with gender identity—also silently and passively expressed his opinion, “unaccompanied by any disorder or disturbance.”

It’s hard to see exactly how his simple wearing of a T-shirt would not fit within the framework of the Supreme Court’s Tinker decision.

Talwani also seems to have missed this distinction from the Tinker court: “[F]or … school officials to justify prohibition of a particular expression of opinion, it must be able to show that its action was caused by something more than a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint.”

The “discomfort and unpleasantness” experienced by any LGBTQ+ students at Liam’s middle school seems to be the real issue in his case.

More than just an exercise in judicial activism on the part of the judge, Liam’s case illustrates vividly how even noncontroversial, mainstream positions have become increasingly restricted in the space of gender identity and transgender “rights.” (Other attorneys have joined with this one in criticizing Talwani’s ruling, including here and here.)

Real debate—not government mandate—is required when it comes to gender identity.

This entire episode is a reminder of how easily “hate speech” arguments and “safe space” demands can mute the bravery and common sense of students such as Liam Morrison—who did not, as the Supreme Court remarked in Tinker, shed his constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gate.