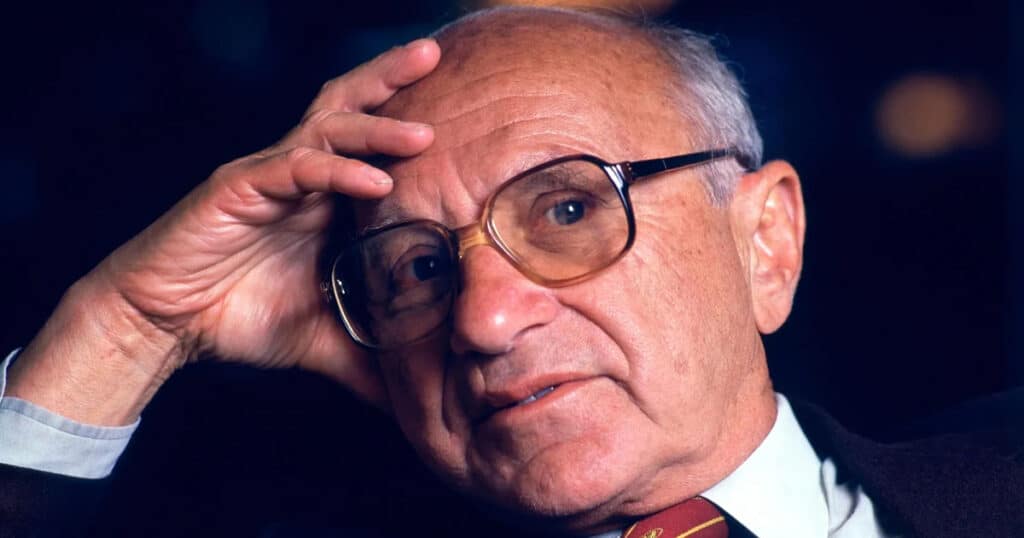

Milton Friedman’s Vision in Education Becomes Reality

On the occasion of his “eleventy-first” birthday, the hobbit Bilbo Baggins famously disappeared. On July 31, we celebrate what would have been the 111th birthday of another man who was diminutive in size but larger than life in spirit: Milton Friedman. Were he to reappear today, he would likely marvel at how much progress has been made on issues about which he cared so deeply.

In particular, Friedman would likely be amazed at the expansion of education freedom over the last year as well as the landmark Supreme Court decision to eliminate racial preferences in education.

In the past three years alone, more than 20 states have enacted new education choice policies or expanded existing ones, including eight states that are in the process of implementing Friedman’s vision of universal school choice.

And last month, the Supreme Court decided jointly in two cases brought by Students for Fair Admissions against Harvard and the University of North Carolina that the equal protection clause prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, including in college admissions.

For Friedman, these two issues were closely connected. He was convinced that black Americans could not obtain equality of opportunity unless they had access to school choice. But he also understood that if those educational opportunities were allocated with racial preferences, that system might help a few but would inevitably undermine access to quality options for most black Americans.

Friedman once remarked, “If you think that there is a way out of this by getting government to pass laws especially to benefit [black Americans] you are kidding yourself. That isn’t going to happen.”

The problem, he astutely observed, is that majorities pass laws and black Americans are a relatively small minority. It is unreasonable, he argued, to expect majorities to pass laws that would undermine their own interests while advancing the interests of a minority. As he put it:

Temporarily … affirmative action may benefit some blacks, some low-income people, but if you believe that Supreme Court decisions are going to be able to stop a majority of the population, which is prejudiced, from using this power to benefit themselves rather than the people who are disadvantaged, you’re kidding yourself. That’s not the way out.

Affirmative action may have elevated select members of minority groups, but it did so at the expense of others, particularly Asian Americans. According to author Kenny Xu:

In the case of Harvard, race is not simply used as a tiebreaker in admissions. A 2013 internal Harvard study revealed by the [Students for Fair Admissions] lawsuit showed that had Harvard only considered academics, Asians would make up 43% of Harvard’s student body. Adding legacy, athlete recruitment, “extracurriculars,” and a “personal” score lowered Asians to 26%. Finally, in the years the internal Harvard study looked at, Asians actually made up only 19% of the student body.

Even the supposed beneficiaries of racial preferences in college admissions are harmed by them in at least three ways. First, artificially advancing some applicants undermines incentives for achievement within their racial communities, as it detaches accomplishments from rewards.

Second, as the great economist Thomas Sowell (a former student of Friedman) observed, racial preferences lead to a “mismatch effect” that leaves “many blacks and Hispanics who likely would have excelled at less elite schools … in a position where underperformance is all but inevitable because they are less academically prepared than the white and Asian students with whom they must compete.”

And third, as Justice Clarence Thomas has argued, racial preferences “stamp [their beneficiaries] with a badge of inferiority” that “taints the accomplishments of all those who are admitted as a result of racial discrimination” as well as “all those who are the same race as those admitted as a result of racial discrimination” because “no one can distinguish those students from the ones whose race played a role in their admission.”

Friedman was very clear that meaningful progress depended on abolishing both racial discrimination and racial preferences:

We want a society in which people can celebrate their own special ethnic background. But that’s a very different thing from a society which somehow takes ethnic characteristics as a criterion for preference or lack of preference, from a society which moves away from the doctrine of color-blindedness to the doctrine of so-called affirmative action. That’s the problem.

There are many advocates within the school choice movement who agree with Friedman on the benefits of expanding educational freedom but somehow ignore his message about the harms of racial preferences. They favor private school choice, but only for urban school districts with large minority populations or only when programs are targeted toward low-income families. They favor charter schools, but only those that focus on minority students with “culturally responsive” models. They believe that students learn the most from teachers who share the same skin pigmentation and they seek preferential funding, training, and hiring of black teachers to accomplish this.

Friedman would be thrilled to see that all students, regardless of class, color, or creed, are now eligible for private school choice in eight states. But he would be aghast that some claiming to favor school choice would prefer that these opportunities be allocated with racial preferences.

Friedman had no objection to people maintaining strong racial and ethnic identities: “I believe it’s highly desirable for people to be able to pursue their own values, to have whatever ethnic values they want, provided they do it voluntarily and do not interfere with the freedom of others to do it also. We want a society of variety and diversity.”

But he would have objected vigorously to the idea that government policies, such as critical race theory in public school curriculum, matching the race of students to teachers, or racial targeting of education opportunities, were necessary to cultivate those group identities and achieve progress for members of those communities.

Friedman was once asked directly about this issue: “Don’t you think it’s through ethnic solidarity that many minority groups were able to make advances in the American society?”

To which Friedman replied, “Not in the slightest. If you look at the way in which ethnic minorities made advances, it was not through ethnic solidarity. It was through the free market.”

On Milton Friedman’s 111th birthday, we should celebrate the remarkable growth toward a free market in education that we have seen in recent years. But we should also heed Friedman’s warning that those benefits of freedom can only be enjoyed if we avoid the coercion of racial preferences.