Beijing’s House of the Dragon

Why Xi’s Actions Show This is Unlike Moscow’s Game of Thrones

The authoritarian regimes of China and Russia read like the fantastical universe of George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Fire and Ice-made famous by HBO’s Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon. One is trapped in the musings of attempting to cobble together its former greatness in Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine, assassinations at 30,000 feet, and jockeying competing alliances in a Game of Thrones style fashion. While the other, China, is mired in internal political strife, corruption, extramarital affairs, and seeming concern that their desired greatness is fading from reach-like the setting of House of the Dragon. While Russia’s Game of Thrones involves warring factions jockeying for loyalty to the throne, China’s House of the Dragon is about maintaining dominance, legitimacy, and power through violence, scheming, and control of power. But what does it all mean?

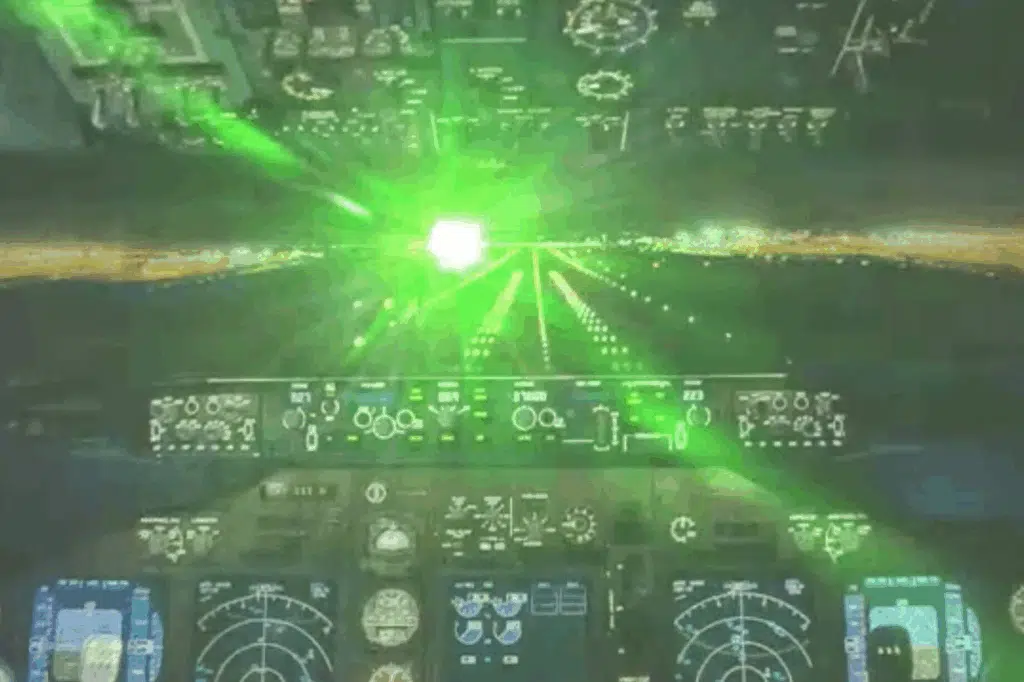

The latest episode of Moscow’s Game of Thrones ended spectacularly with the plane “crash” of former Putin confidant turned rebel, Yevgeny Prigozhin. Less spectacular publicly, yet still dangerously fascinating to watch, is the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) House of the Dragon’s removal of senior Chinese military and civilian officials by General Secretary Xi Jinping. While Vice News asked the question earlier this year who would win Moscow’s Game of Thrones, how do we account for the same questions for Beijing’s House of the Dragon?

Xi’s actions are not new. They go back well over a decade when his anti-corruption drive purged CCP ranks of corrupt officials- who also just happened to be Xi’s political enemies. This summer, those purges have continued with Xi implementing sweeping changes at the highest across all elements of China’s leadership structure. Xi removed first the leaders of the PLA Rocket Force for alleged corruption, he then removed China’s Foreign Minister Qin Gang, who according to the Wall Street Journal was removed due to an extramarital affair. Finally, Xi removed China’s Minister of National Defense and standing member of the PLA’s powerful Central Military Commission, General Li Shangfu. While the latter’s position is not equivalent and lacks the same power and authority as the U.S. Secretary of Defense, these removals and arrests should not be underplayed. Remember, this is not a nation-state army like the U.S. or even Russia. China’s military and security apparatus operate at the behest of the CCP, and specifically Xi. This is unlike the dynamic and less controlled Russian Game of Thrones.

In hindsight, Prigozhin’s actions were not a surprise because he had long telegraphed his displeasure publicly with Russia’s war effort, but his death was done in cold Russian fashion. Let’s call it Putin’s own “Red Wedding Revenge.” However, Western analysts and the press seemed caught off guard by Xi’s firings and removals. Like the first season of House of the Dragon with considerable time gaps between episodes, the CCP’s internal affairs and Xi’s firings play out over the years. They are anything but abrupt. Like Martin’s universe, these volatile events are inherently linked—if only, by the close chronology of their occurrence—and deserve a closer look at their underlying issues. Specifically, how does CCP ensure China does not become its own Game of Thrones. There is historical precedence after all from the Warring States period. CCP thinking and historical interpretation have evolved from historically blaming complexity, personality, and economic stagnation, to now implicating ideological decay as the decisive factor of the Soviet Union’s collapse.

There once was a saying in Mao’s 1950s China: “Russia-China’s Tomorrow.” For decades, both Beijing and Moscow have pursued regime security strategies that radically differ and no longer prove this aphorism to be true. Take Putin’s Russia for example. The atmosphere that enabled Putin’s rise and power structure over the past 20-plus years has been one of corruption, patronage, fear, and politically motivated killings. As recently written in the New Yorker, “more than anyone else in Russia, Prigozhin had used the war in Ukraine to raise his profile.” While Prigozhin’s rise is exceptional even in the Russian system, he exploited and benefitted from intricacies in the crony Russian system that confers patronage to those who are complicit in Putin’s criminal exercises of power. Prigozhin was a singular figure in Russia’s international atrocities in Syria, Africa, and now, Ukraine – and in Ukraine, he served another unique purpose for a time: one of an escape valve, where he could air grievances about Russia’s performance in the Russia-Ukraine war while insulating Putin from wider public backlash. The Game of Thrones is indeed complicated and messy to watch in Russia, but the show illuminates fissures in the Russian system and gives context to contrast China’s own House of the Dragon. Put simply, the CCP (and Xi) have spent decades understanding Russia’s circumstances and insulating itself from Russia’s ills.

The CCP are astute observers of Russia’s contemporary struggles and the lessons of the Soviet Union’s collapse, and their thinking continues to evolve and inform its own strategy to avoid repeating the same mistakes. Several recent papers have reflected this dynamic in CCP thought, including extensive translations of the newly revised 2021 history translated earlier this year is completely absent any diagnosis of the structural issues that are well documented in the USSR’s collapse. Xi puts corruption, ideological decay, and failure to adhere to Party standards as reasons for the USSR’s collapse. Understanding how CCP political thought is evolving, and how the CCP is recasting key historical events, are critical for clearer insights that put into context two key purges Xi has undertaken: the first purge of his political opponents a decade ago upon taking power, where he jailed for life his primary political opponent, Bo Xilai, former a Vice-Chairman of the PLA’s Central Military Commission (CMC), only surpassed by removing a current member of the CMC.

The inference from Xi’s contemporary speeches is that Beijing increasingly saw corruption and ideological impurity as accelerants for a regime’s demise. Xi’s comments in 2012 elucidate this fact. At the time, he remarked: “Why was the Soviet Union dissolved? Why did the CPSU [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] collapse?” One important reason was the struggle in the ideological field. Historical nihilism rejected Soviet Union history, CPSU history, Lenin, and Stalin; it messed up the thinking. As a result, party branches perished; the party could not even control the military. Therefore, a big party like the CPSU dissipated; a big socialist power like the Soviet Union collapsed. This is a vital historical lesson.” Xi’s purges and litany of policies requiring greater adherence to party ideology show his determination to prevent the past from repeating and becoming a Russian Game of Thrones.

So, what do we need to understand? Expertise and insight into today’s increasingly ideological and nationalistic CCP are critical for forecasting conditions that could result in similar leadership volatility. As previously discussed, history, Xi’s words, and actions are key indicators to look at. However, be wary of anyone who predicts exactly what comes next.

While understanding Xi Jinping’s decision-making is inarguably important, trying to discern the place and timing of every decision is an extremely arduous task. No one’s crystal ball will be able to predict exactly where and when future firings might happen. As the CIA wrote for the freshly minted President Ford in August 1974 in the waning years of Mao’s disastrous Cultural Revolution, “Chinese Communist ideology seems certain to continue to play a critical role in shaping China’s programs of political, economic, and social development.”

Policymakers, analysts, military commanders, and the private sector now, more than ever, should look to understand the CCP’s driving ideology and how it interprets its own, and others, history. Failure to do this will leave us continually surprised about what comes next in the CCP’s House of the Dragon.

William O’Hara is a career Department of Defense and Intelligence Community employee. He is currently the senior China planner and strategist at U.S. Special Operations Command. The views expressed here do not represent those of U.S. Special Operations Command, U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

This article was originally published by RealClearDefense and made available via RealClearWire.