Inside The Market-Driven Plan That Could Actually Lower Prescription Costs

Health insurance middlemen originally tasked with finding better deals for consumers have come under increased scrutiny by prominent U.S. Senators and members of Congress as prescription costs are soaring at a rate faster than Bidenflation.

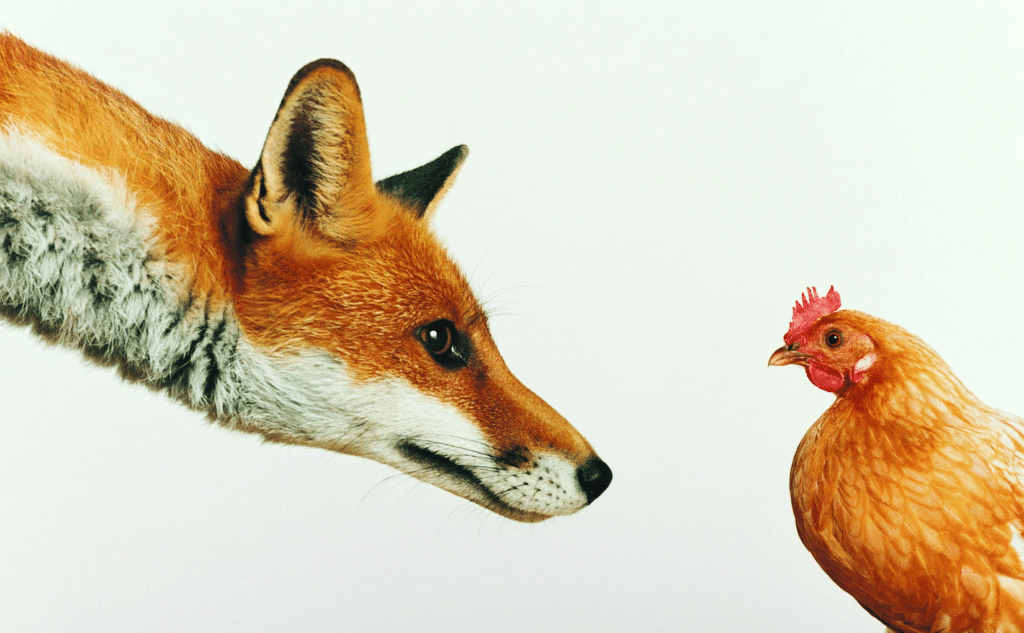

While having such advocates in the U.S. healthcare system has (arguably) worked well in the past, there’s now a clear conflict of interest at play. Is this a case of the fox guarding the hen house?

The industry contends rising and rapidly fluctuating prescription costs is partially due to increased demand and availability of new cures. Technology will “evolve” to give consumers more power and choices over their pharmaceutical purchases, advocates say.

But critics claim there’s a systemic failure: that Pharmacy Benefit Managers (or PBMs, who have since the late ’60s negotiated on behalf of health insurance companies, self-insured employers, and government programs, with drug manufacturers), have almost unchecked authority. According to pharmacist Will Douglas in a recent op-ed, PBMs have “the power to decide which drugs allowed in [plans] and at what price.” (ed note: Douglas is a Republican Texas House candidate attempting to unseat Democratic Rep. Rhetta Andrews Bowers in an east Dallas-area swing district in the 2024 election).

“Because PBMs get paid a percentage of the price of the drugs they allow in the plan, they make more money when drug prices are high,” Douglas wrote. “Rather than seeking equally effective drugs at lower prices, PBM’s incentive is to choose more expensive drugs because the PBM then makes more money.”

‘Profit-driven monsters’

Nowhere is this more evident recently than sticker shock over Semaglutide products such as Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus and similar drugs. At first hailed as a major advancement for diabetics to help regulate the body’s insulin production, a side effect was quickly noted: that of rapid and dramatic weight loss. Online videos featuring “the TikTok diet” soon spread, leading to wait lists for the wonder-drug whether they needed it or not (See previous coverage in our sister publication The Hayride on the hypocrisy between advertising revenue and short supply of the new drug).

Coupons were offered to the first wave of Ozempic consumers, driving the price down from $1,000 or more per month to practically free in many cases. But like most coupons, they expired, and those who had become accostomed to the medication — diabetics and those simply wanting to lose weight alike — soon found themselves unable to afford to continue.

Prescription costs have become “anything but transparent” as a result of this double-standard, a health consumer blog noted. “We cannot easily determine, for example, if the higher list price of Wegovy for obesity (compared to Ozempic for diabetes) results in a higher net price or not. It’s common for PBMs to demand big discounts for innovative new therapies where coverage is a challenge. That incents a pharmaceutical company to charge a higher list price so it can gain coverage and recover its huge investment in R&D.”

While FDA clearance for Semaglutide as a weight-loss drug recently (and finally) opened the door for some cheaper alternatives, the teeter-totter of drug pricing continues to confound pharmacists, especially smaller counters, Douglas continued in his op-ed.

“As someone who spends day in and day out behind the pharmacy counter, I’ve had a front-row seat to the theater of absurdities that is the American prescription drug market,” he wrote. “[PBMs] were conceived as cost-saving middlemen but have morphed into profit-driven monsters that bully the patient and the neighborhood pharmacy.”

A legislative solution

Douglas said he is supporting H.R. 2880 in hopes that it would tie PBM income to actual market prices that are clearly advertised, rather than “the Gordian knot that has kept us entangled in high prices and questionable practices.”

H.R. 2880, dubbed the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act, is languishing in the House, but a companion in the Senate may have a stronger chance of moving soon after committee passage in the spring. A cursory reading of the bill’s text indicates it would attempt to keep PBMs from charging inconsistent, ever-changing amounts for the same drug’s ingredient-cost or dispensing fee.

The bill, Douglas explained, demands that for every drug included in what’s known as a formulary, PBMs must report how its national average cost compares to therepeutic alternatives. “Think of it as requiring a car dealer to tell you how the mileage of the car you’re looking at compares to other cars in the same category,” he said.

Rebates and administrative fees would also be clearly reported under the bill, if passed.

While this may seem like more loops in the aforementioned Gordian knot, a policy analyst for the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF) says it is as close to a market-based solution as can be found given the system’s complexity.

“This shouldn’t be a tough sell,” David Balat of TPPF’s Right on Healthcare initiative opined. “The PBMs and insurers already claim they do this. The problem is there is no evidence it’s true.”

In Texas, for example, the PBMs “spread out” (see more on that phrase below) just $10 million to enrollees from the rebates in 2020, while they and the insurers “pocketed” over $2.2 billion, Balat noted. Yet premium prices continue to rise.

“I’m no friend to expanding government power — and this bill doesn’t do that. Instead, it empowers consumers with more information,” Balat said, adding that PBMs are soon to become a $619 billion industry in the U.S.

The Senate bill’s author, Republican U.S. Sen. Chuck Grassley, claims that three PBM companies currently control 80% of the market. Making matters worse, Grassley’s office noted some PBMs have been known to engage in “spread pricing” where a PBM charges a health insurance plan more to process a prescription than it reimburses the pharmacy, keeping the difference. For example, a PBM will keep $10 while charging insurance $100 and reimbursing a pharmacy only $90. This complicated system has led to the U.S. having the highest prescription drug prices in the world, despite it being a clear leader in production, the senator concluded.

Having PBMs actually work to reduce costs for the consumer, Grassley’s press release suggested, could bring prices down in a way not seen in decades — and reduce the deficit by $740 million over the next decade.

Bipartisan support

Grassley pointed out the effort to bring transparency to PBMs is a bipartisan push. President Joe Biden, former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra have been receptive to the members of the Problem Solvers Caucus’s Health Care Working Group in the Senate. His bill is co-authored by U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell, a Washington Democrat. Even retired Sen. Ron Wyden, a Democrat who is about as far-Left as it gets, called the presence of PBMs in the health care system “clear a middleman rip-off as you are going to find.”

In short: the bill has the suppport to pass, but has yet to become a priority.

In March, the Senate Commerce committee passed Grassley’s bill, S. 127. The bill now awaits introduction to the Senate floor, which is currently controlled by a narrow Democratic majority.

‘Reimagining’ as an alternative

Meanwhile, back at the hen house, the industry continues to claim it is “evolving” and is “reimagining” the way prices are advertised, and without any new legislation. The stated goal is to arrive at a “value-based model” (ed note: which may differ from a market-based model — another story for another time).

A press release from Blue Shield of California underscored that in 2021, the American healthcare system spent more than $600 billion on prescription drugs – about $1,500 per person, per year. The company signaled hope that by strengthening partnerships with major consumer outlets such as Amazon and CVS they can save consumers hundreds of millions of dollars, while agreeing that the U.S. drug supply chain is “convoluted and inefficient.”