Columbia Lawlessness Springs From Free-Speech Hypocrisy

In the early hours of Tuesday, April 30, protesters, including some calling for Israel’s elimination, stormed Columbia University’s Hamilton Hall. After smashing glass and blockading doors, as reported by CBS New York and other news outlets, the protesters hung an “intifada” banner from the building. At the request of the university – and less than 24 hours after students first occupied one of the buildings that their counterparts had taken control of 56 years before at the height of the 1960s campus upheavals – the NYPD removed the protesters late Tuesday evening and arrested dozens of them.

The protesters’ seizure of the historic site, which followed the university’s failure to enforce several deadlines for students to dismantle their tent encampments on Columbia’s main quad, was not inevitable. Nor was it unavoidable that, as the Columbia Spectator reported, “faculty in orange vests,” which press images show had the word “FACULTY” on the front and back, “formed a line in front of the entrance” of the prohibited encampment. A responsible university administration and professoriate, however, would have forestalled these heedless acts. Instead, Columbia’s conduct – over the last few weeks and over the last few decades – fostered them.

On April 22, Columbia University Provost Angelina V. Olinto and Chief Operating Officer Cas Holloway distributed a letter informing the university community that all classes on the university’s main campus would be “hybrid” – allowing for remote or virtual learning – through the semester’s end. The university administrators explained that “safety is our highest priority as we strive to support our students’ learning and all the required academic operations.”

Provost Olinto and COO Holloway omitted that the safety in question was primarily that of Columbia’s Jewish students, who faced antisemitic slurs and calls for violence. Nor did Olinto and Holloway acknowledge that a principal threat to Jewish students’ safety came from fellow Columbia students.

Columbia President Minouche Shafik also issued a statement to the university community on April 22. Writing that she was “deeply saddened by what is happening on our campus,” Shafik stressed the need for “better adherence to our rules and effective enforcement mechanisms.” She deplored “many examples of intimidating and harassing behavior on our campus” while asserting that “antisemitic language, like any other language that is used to hurt and frighten people, is unacceptable and appropriate action will be taken.”

So grim was the situation that, according to the Columbia Spectator, on Sunday, April 21, Rabbi Elie Buechler, who works with orthodox Jewish students at Columbia, wrote in a group chat that “the events of the past few days, especially last night, have made it clear that Columbia University’s Public Safety and the NYPD cannot guarantee Jewish students’ safety in the face of extreme antisemitism and anarchy.”

A university that fails to prevent intimidation and harassment betrays its mission, which is to create a community of learning in which students and professors can acquire knowledge and refine their ability to think carefully, creatively, and incisively. Columbia’s failure stems from decades of dereliction of duty by elite universities. Not least of the derelictions has involved encouraging students to believe that a university’s principal purpose is to promote progressive opinions about social justice.

The dereliction of duty continued apace at Columbia following the university’s April 22 decision to offer courses on a hybrid basis (on May 1 Columbia informed students that all remaining “academic activities” and final exams on its main campus this semester would be conducted online). A few days earlier President Shafik ordered students to dismantle the encampment they built on the university’s main quad. When they delayed, she sought the assistance of the police, who arrested more than 100 demonstrators. She then wavered, allowing protesters to construct a new encampment elsewhere on the quad in which, Michael Powell observed in The Atlantic, “hundreds of students and their supporters at what they fancy as the People’s University for Palestine sit around tents and conduct workshops about demilitarizing education and fighting settler colonialism and genocide.”

Shafik’s original directive to remove the encampment and her decision to call the police were entirely justified. As New York Times columnist David French explained, peaceful protests and, in extreme situations, civil disobedience – in which those who break the law to challenge what they regard as injustice peacefully accept the lawful consequences of their disobedience – are proud features of the American political tradition. But as my Hoover colleague Eugene Volokh observed, “disruptive protests” are neither protected by the First Amendment nor part of the liberty of thought and discussion essential to liberal education. Columbia has an overriding obligation to prevent the indefinite occupation of university property because such lawlessness impedes the university’s educational mission by harming health and safety, inciting physical clashes, and allocating a portion of neutral campus space to one side in a charged political dispute.

Shafik, however, handled the protesters’ subsequent rebuilding of their prohibited encampment in exactly the wrong way: She opened negotiations with students who were acting in flagrant defiance of the university’s clear instructions.

It is proper, even laudable, for university presidents to welcome to their offices students concerned about university governance. But presidents and other administration officials should not negotiate with students flouting the university’s rules and regulations, particularly when the students demand changes to university policy in exchange for compliance with the university’s code of conduct. Rather, universities should inform disruptive protesters that compliance with school rules is a non-negotiable precondition for discussions. Administrators should also discipline students who persist in prohibited activities. No less than other organizations, universities that indulge lawbreaking teach lawlessness and beget more of it.

What explains university administrators’ cooperation – hardly restricted to Columbia – with students’ lawbreaking? It is not just a matter of faulty leadership. And CNN journalist Fareed Zakaria diverts attention from the heart of the matter with his vague suggestion that the reason for “the protests, polarization, intimidation and general bitterness” on campuses today is that colleges and universities “have weakened as actual communities, where people mingle, interact and get to know and trust each other.” Rather, universities’ accommodation of rule-breaking by those who loudly demand the destruction of the nation-state of the Jewish people stems in significant measure from administrators’ and professors’ free-speech hypocrisy.

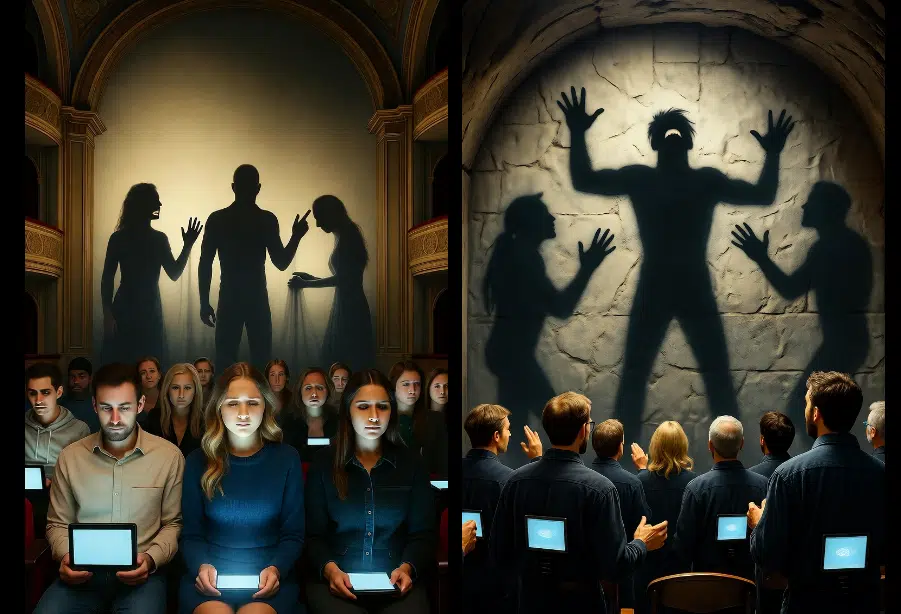

In the decades preceding the Hamas jihadists’ Oct. 7 orgy of murder, rape, and kidnapping in southern Israel, elite universities endeavored to shelter progressives on campus from the slightest offense to their sensibilities. Confusing free inquiry and robust debate with intimidation and harassment, administrators endorsed – and most faculty members either embraced or acquiesced in – the implementation of trigger warnings, policing of microaggressions, establishment of “safe spaces” and “free-speech zones,” creation of bias response teams, and more. By these censorious means, university officials undertook to thwart the expression of sentiments, opinions, ideas, and even facts that displeased the progressive spirit.

Identity-politics-inspired censoriousness received high-level sponsorship in 2015 when Yale University President Peter Salovey caved in to student clamor to enforce progressive orthodoxy. Erika Christakis, a Yale dormitory administrator – and expert in childhood education – outraged many undergraduates by distributing an email suggesting that students themselves and not the university should supervise college Halloween parties and that they and not the university should bear responsibility, where necessary, for informing their classmates when their costumes were inappropriate. Salovey took extraordinary steps to placate the students enraged by the prospect of attending a campus Halloween party without the protection of Yale authorities to enforce progressive Halloween-costume norms barring supposedly culturally insensitive attire. He promised to launch a $50 million, five-year, university-wide initiative to enhance faculty diversity and to develop a transformative, multi-disciplinary center to study race, ethnicity, and other aspects of social identity.

That Yale’s sedulous care for student feelings applied only to progressives and select minorities has been exposed for all the nation to see since Oct. 7 by elite university presidents – starting with former Harvard President Claudine Gay, former University of Pennsylvania President Liz Magill, and still MIT President Sally Kornbluth. Invoking the very principles of free speech of which their universities have made a mockery, they provided wide latitude for the expression of vile calls for Israel’s destruction.

New York Times columnist Ross Douthat recently contended that the double standard stems from fashionable settler colonialism ideology: “With its unusual position in the Middle East, its relatively recent founding, its close relationship to the United States, its settlements and occupation, Israel gets to be the singular scapegoat for the sins of defunct European empires and white-supremacist regimes.” That’s right but does not go far enough. The settler colonialism ideology that whips up much of the protest fervor denounces Israel as an agent of American evils in the Middle East, and decries the United States as the preeminent white-supremacist regime.

Meanwhile in The Atlantic, Conor Friedersdorf maintained that universities are caught in a bind: “The tensions here between free-speech values and antidiscrimination law are unusually complex and difficult, if not impossible, to resolve.” To the contrary, the tensions are typical of those that free societies regularly confront, and though such tensions cannot be resolved they can be effectively managed. The proper way to handle the tensions between the vigorous protection of free speech on campus and the prevention of hostile environments that subject members of the university community to intimidation, harassment, and violence is to teach civility and toleration and to employ – and enforce – reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on protests.

University of Florida President Ben Sasse has set a good example. Anti-Israel protesters at UF (I serve as a member of the Academic Advisory Board of the university’s Hamilton Center) led by Students for Justice in Palestine and describing themselves as “occupiers” built an encampment on the campus’s Plaza of the Americas. On April 25, the university issued a brief statement distinguishing between permitted and prohibited activities. “Peaceful protests are constitutionally protected. Camping, putting up structures, disrupting academic activity, or threatening others on university property is strictly prohibited,” the university told The Gainesville Sun on April 26. “The University has clearly communicated this to our students and explained that they can exercise their free speech rights but breaking the law will result in an immediate trespassing order from UFPD and an interim suspension from Student Life.” On April 29, police arrested nine protesters.

One could say that President Sasse can take a firm stand because his public university’s Board of Trustees and his state’s governor, Ron DeSantis, back him. That helps.

The 21 members of Columbia’s Board of Trustees should take note and muster the gumption to put the university’s educational mission first. In the face of politicized administrators, militant or feckless faculty, and lawless students, the board should give its full support to President Shafik – or, better yet, a new president – to uphold the requirements of liberal education.

Colleges and universities that teach civility and toleration and that devise and enforce reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on protests can eliminate disruptive conduct, preserve peaceful protests, safeguard free speech, and maintain their institutions as open fora for inquiry and debate. Amid the intensifying turmoil on the nation’s campuses, such colleges and universities can provide a model for the restoration of higher education in America.

This article was originally published by RealClearPolitics and made available via RealClearWire.