Political Distance

Recently, I published this essay in which I urged libertarians to vote for Donald Trump in the purple states. I favored supporting the candidate of the Libertarian Party everywhere else. In the blue or red states, the vote of freedom supporters would not help Mr. Trump, since he would lose, big, in the former, and win by large majorities in the latter. But in the half dozen or so swing states, a few thousand ballots from liberty-oriented people could be a great help to him.

Pierre Lemieux was not at all convinced that my claim would promote liberty, or was even rational. In this essay of his, he takes issue with me on several points.

For one thing, he maintains that “the ‘swing states’ (his scare quotes) … are only known after the election.” But we have elections all the time, every few years. It is not at all debatable that in recent times these states have had very close results: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Indeed, that is why they are considered purple, neither red nor blue. As I mentioned in my initial Wall Street Journal op ed on this matter “Libertarian nominee Jo Jorgenson received roughly 50,000 votes in Arizona in 2000, when Donald Trump lost the state by about 10,000 ballots.”

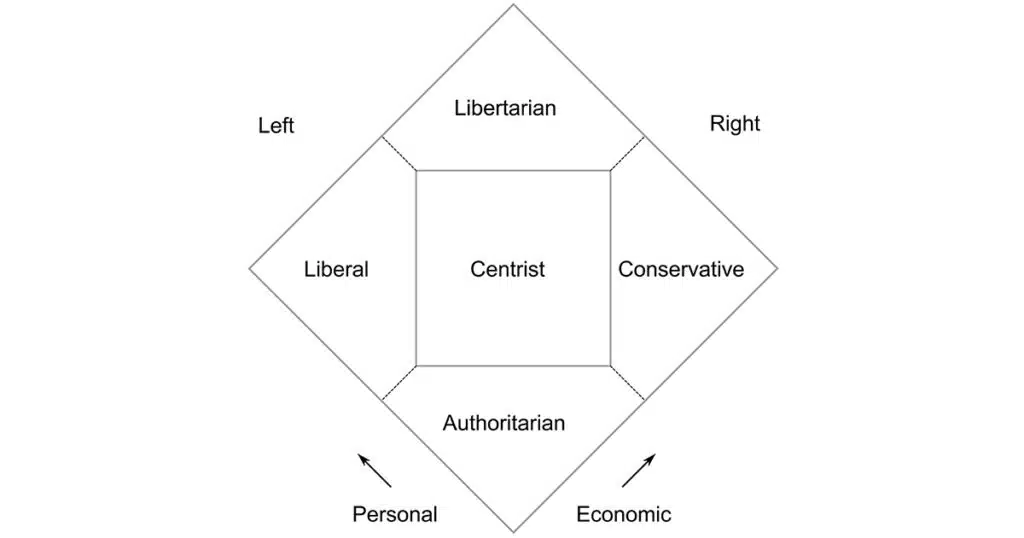

The second arrow in this Canadian libertarian’s quiver is to maintain that in effect there is no such thing as political “distance” and thus my claim that Trump is “a lot better than Joe Biden” in terms of adherence to libertarian principles is not only false, but actually logically incoherent. Why does he make such a strange claim? It is due to the fact that there are no political metrics, such as in the case of height, or weight, or speed, or pulse rate. Why in turn is this the case?

Even if there were only one consideration, one variable, such as tax rates, we still could not make sense of one politician being closer to libertarianism than another. First, not all libertarians agree on the ideal rate of taxation. Therefore, there is no way to measure the “distance” between the ideal level of taxes and the goals of the two major candidates for president. Second, although he does not mention this point, there are many types of taxes: suppose Kamala Harris wants to lower social security taxes by 15% but raise income taxes by 10%, whereas Trump seeks the inverse. What is a poor libertarian to do but throw up his hands in confusion, if I can put accurate words in my critic’s mouth in such a case.

But matters are far worse than that. For there is not just one dimension to be considered; there are dozens, scores, maybe hundreds of them. Yes, Trump beats out Biden (and by extension, his successor Kamala Harris) on pardoning Ross Ulbricht, Lemieux could reasonably concede, but suppose the Democratic candidate is closer to libertarians on issues such as the trade he mentions, but he could have added abortion, or drug legalization or rent control, or a myriad of other issues. He concludes: “Minimizing the distance between ‘us’ and the presidential candidates becomes impossible.”

I am not at all convinced. Of course this commentator is correct in pointing to difficulties in measuring political distance. But, surely, it is obvious that Ron Paul is closer to libertarianism than is Bernie Sanders; that Rand Paul beats out AOC in this sweepstakes by a large margin; that Gandhi is closer to our philosophy than is Hitler. And, yet, according to this theorist, all of these comparisons are “impossible.”

What error is he committing? It is one of perfectionism. The perfect is the enemy of the good. Yes, we cannot easily specify objective numbers depicting political position, but it can be done! The Nolan Chart is one primary example. Another is the attempt to determine which country is freer than which other. There are numerous dimensions here, too. Yet, it take no great wisdom to know that Switzerland is freer than Cuba, and that Venezuela lags, greatly, behind Lichtenstein in such a characteristic. Strangely, Lemieux himself acquiesces in, acknowledges, the logical coherence and productivity of attempts to rate countries in terms of economic freedom. Why he cannot do so in this present context must remain a mystery.

The third reservation pointed to by this scholar is that no one voter can, all by his lonesome self, change any electoral result: “we must not lose sight of a simple but often ignored reality: the tiny probability that an individual vote will be decisive, that it will ‘swing’ anything. It never happened in a presidential election and is unlikely to ever happen. A rational individual will not vote with the intention to change the election’s result.”

But this, too, is highly problematic. It implies that no one should vote. No one at all. I tell you, if everyone in the country decides to follow his advice, apart from me, I, alone, will determine who will be the next president of the United States. Hint: it will not be the Democrat.