What I Saw in Springfield, Ohio—The Challenges Residents Face From the Haitian Immigration Surge

Last week, I went to Springfield, Ohio, to see for myself this town that has symbolized the raging debate about mass illegal migration, which remains a top concern of voters.

Above the noise and distraction, my conclusion was that Springfield symbolizes two main issues.

First, you can’t have open borders and a welfare state.

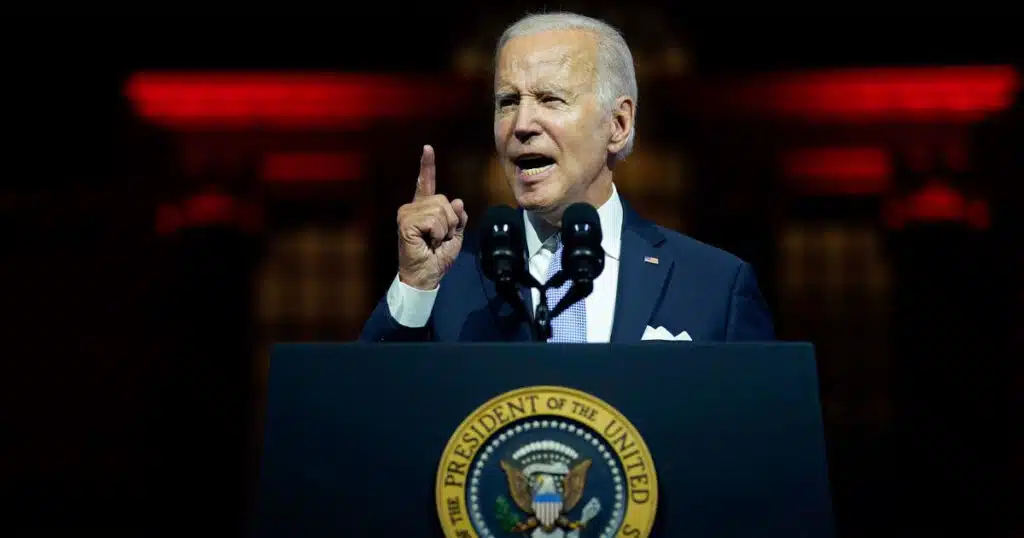

Second, you can’t have a functioning nation if you don’t follow the rule of law. Congress has the duty and authority to legislate the process for immigration into the U.S. That includes who comes in, how, from where, under what conditions, and how long they can stay. Previous presidents have tested the limits of their executive authority in trying to push this envelope. But Joe Biden and his “border czar,” Kamala Harris, have ripped up the envelope entirely.

My first stop in Springfield was the Clark County Department of Job and Family Services. Outside, the signs were in Spanish, Haitian Creole, and English—in that order.

The dropbox for documents had an additional handwritten sign in Creole and Spanish.

Above the noise and distraction, my conclusion was that Springfield symbolizes two main issues.

First, you can’t have open borders and a welfare state.

Second, you can’t have a functioning nation if you don’t follow the rule of law. Congress has the duty and authority to legislate the process for immigration into the U.S. That includes who comes in, how, from where, under what conditions, and how long they can stay. Previous presidents have tested the limits of their executive authority in trying to push this envelope. But Joe Biden and his “border czar,” Kamala Harris, have ripped up the envelope entirely.

My first stop in Springfield was the Clark County Department of Job and Family Services. Outside, the signs were in Spanish, Haitian Creole, and English—in that order.

The dropbox for documents had an additional handwritten sign in Creole and Spanish.

Inside, I saw a waiting room filled with people, a line outside the door, and more people arriving regularly. I spoke to several in French (which many Haitians speak or understand, as their Creole is a derivative of French). One family told me they had been living in Brazil for eight years but decided to come to America instead as it was closer to Haiti and culturally more comfortable for them.

The fact that they were safely settled outside Haiti in Brazil would make them ineligible for asylum in the U.S., but as with thousands like them, the Biden administration pretends they are asylum-seekers, not asylum shoppers. In other words, that they were actually fleeing persecution in their home country rather than simply looking for better economic opportunities.

I estimated that the majority of applicants in the office that morning were Haitian.

The Haitians are here thanks to a mix of dubious schemes perpetrated by this administration and possibly the illegal use of the president’s executive authority: Parole, Catch-and-Release, Temporary Protected Status—I wrote more about these mass-migration facilitating fudges here.

In brief, the Biden-Harris Department of Homeland Security either allows inadmissible aliens to enter the U.S. on the assumption they will claim asylum or grants them an indefinite delay from deportation proceedings. Then, the federal government gives money—at least a billion dollars a year since 2021—to a range of nongovernmental organizations to distribute these aliens throughout the country to places like Springfield.

At the Job and Family Services department’s reception desk, there were photocopies of forms instructing people how to apply for a range of federal benefits. A few were in English, but a much larger number were in Haitian Creole. Thanks to a reform law passed in 1996, most legal immigrants can’t apply for most federal welfare programs for five years. In theory, illegal immigrants aren’t allowed to tap them either, although they can access certain benefits centered on mothers with children or through their eligible U.S.-born children.

But thanks to poor wording in U.S. law, Haitians can apply from Day One. Cubans and Haitians, as well as some Afghans and Ukrainians, are the few favored nationalities who qualify in this way for a wide menu of federal welfare benefits with no waiting period.

The Ohio benefits application form tells applicants they need an interview to apply for the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, known informally as “food stamps.” They also need an interview to get “cash assistance” but not to get medical or child care assistance.

“Many non-U.S. citizens can receive assistance benefits,” and “Noncitizen Emergency Medical Assistance may also be available regardless of your U.S. citizenship status,” the benefits application form reads.

The first question on the SNAP application (in Creole, too) is whether you want to register to vote—and it says there is a voter registration application attached to the packet.

I spoke to several Springfield residents—homeowners, store clerks, waitresses, and patrons at a local bar. They seemed mostly resigned to, and unhappy about, the social costs of their town’s mini-mass migration. Bad etiquette on the roads and in stores. Car accidents. Overwhelmed schools. More crowded and expensive housing.

But the major financial costs of the Haitian influx are out of sight, borne by far-off agencies or buried in the national budget deficit.

There is a long-running debate about how immigrants affect the U.S. economy. But nearly everyone agrees that, on average, lower-skilled immigrants—which most of the current illegal arrivals are—cost more than they contribute.

A recent report by Daniel DiMartino from the Manhattan Institute concluded that while high-skilled, younger immigrants were an economic benefit to the U.S., “immigrants without a college education and all those who immigrate to the U.S. after age 55 are universally a net fiscal burden by up to $400,000 over their lifetimes.”

Which matters, because according to The Wall Street Journal, 70% of illegal immigrants have no education beyond high school, and only 18% have a bachelor’s degree. Nearly 60% of “households headed by an illegal immigrant use at least one major welfare program.”

In 2016, before both the Trump administration’s tighter border policy and Biden’s open borders, economist George Borjas wrote in Politico, “Put bluntly, immigration turns out to be just another income redistribution program.” He says, “Decades of record immigration have produced lower wages and higher unemployment for our citizens, especially for African American and Latino workers.”

Heritage Foundation economist EJ Antoni wrote back in July that “literally all the net job growth over the last year went to foreign-born workers. Native-born Americans lost over 900,000 jobs.”

Borjas estimates that the annual wealth “redistribution from the native losers [less educated Americans] to the native winners [employers and stockholders] is … roughly a half-trillion dollars a year.”

You can see this playing out in real time in Springfield.

Cities like Boston, Chicago, Denver, and New York have “sanctuary” policies and offer enticements to paroled or released aliens to come there. But other smaller, less equipped places are deluged thanks to the federal government teaming up with activist groups and charities to transport them there. Springfield is a particularly shocking example, because the ratio of Biden-Harris off-the-books mass migrants to U.S. residents is so large—about one in four.

Another example is Charleroi, Pennsylvania, which Chris Rufo recently wrote about in the City Journal. Charleroi is a typical postindustrial small U.S. town. With a population of about 4,000, it has seen an influx of around 2,000 mostly Haitian migrants. This causes the same problems as Springfield but magnified. Schools need interpreters. The police are busier with traffic violations, with so many drivers used only to Haiti’s chaotic roads or just learning to drive. Health care providers are burdened with more nonpaying patients.

As Rufo writes, “Residents say they had no choice—there was never a vote on the question of migration; it simply materialized.”

Both Charleroi and Springfield are not wealthy areas, but they still have local industries. These employers want to hire labor as cheap as they can. When a labor market functions properly, higher demand for labor leads to higher wages. But an endless surge of migrants from very poor countries keeps wages at rock bottom.

In both towns, labor brokers get paid to bring migrants in for low-wage jobs. In Springfield, the main broker seems to be First Diversity staffing. “Diversity” is an ironic name, since although the company website’s stock photo shows a diversity of sexes and races, their labor force seems to be nearly all Haitian migrants.

Rufo writes that Charleroi has at least three such staffing agencies, which rake off the top about a third of what they charge employers for each worker’s hourly wage.

In both Springfield and Charleroi, local business owners and politicians own substantial rental properties. Springfield’s mayor owns several rental houses. In Charleroi, the owner of local business Fourth Street Foods also appears to own more than 50 rental houses.

It’s hard to blame businesspeople for being businesspeople. They are responding to market conditions and acting rationally. But their gain is a loss for American citizens and legal immigrants, whose wages and benefits won’t rise and who have to pay through their taxes to support the very workers who are undercutting or supplanting them.

The blame is entirely on the Biden-Harris administration. The mass migration they are encouraging is incentivizing a few Americans to profit off the immiseration of their fellow countrymen.