Why Abolitionists Defended Free Speech

Today the immorality of chattel slavery is painfully obvious, but that has not always been the case. In 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court held that a black man like Dred Scott was “reduced to slavery for his benefit.” In 1861, the vice president of the Confederacy similarly declared that it was a “great physical, philosophical, and moral truth” that “slavery subordination to the superior race” was black people’s “natural and normal condition.”

These were not exclusively Southern opinions. In 1837, the governor of Illinois denounced Northern abolitionists because, he said, “if I read my Bible right, which enjoins peace and good-will as the first Christian duties, it must be wicked and sinful to agitate this subject in the manner it has been done by some Abolitionists.” In his view, fervent opposition to slavery, not slavery itself, was the moral evil in the United States.

State legislatures, governors, postmasters, members of Congress, courts, mobs, and even presidents did what they could to stifle antislavery speech and press. As one New Englander living in North Carolina observed, “In bondage there is no freedom of speech.”

From the perspective of white Southerners, abolitionism promoted false narratives that simply could not be tolerated. The South Carolina legislature, for example, resolved that it would not wait “until our enemies have built up, by the grossest misrepresentations and falsehoods, a body of public opinion against us, which it would be almost impossible for us to resist.” Government suppression of antislavery speech, by this logic, was necessary to stop the spread of what today might be styled disinformation.

Abolitionists countered these arguments by insisting that free expression was the only way to pursue truth. After spending 49 days in jail for allegedly libeling a slave trader, William Lloyd Garrison wrote, “Free inquiry is the essence, the life blood of liberty.” A committee of the New York state legislature agreed, declaring that “all errors and differences of opinion” on political matters ought to be determined by the “tribunal” of public opinion because “a corrective of the evil will be generally found in the force of truth.”

Transcendentalist minister William Ellery Channing made a powerful case for free expression in an 1835 book titled “Slavery.” “Of all powers, the last to be intrusted to the multitude of men is that of determining what questions shall be discussed,” he wrote. “The greatest truths are often the most unpopular and exasperating; and were they to be denied discussion, till the many should be ready to accept them, they would never establish themselves in the general mind.”

For society to progress, Channing continued, there was nothing more essential than “the exposure of time-sanctioned abuses, which cannot be touched without offending multitudes.” If a political majority was permitted to “dictate or proscribe subjects of discussion,” he said, society would be struck with “spiritual blindness and death.” Channing concluded, “The world is to be carried forward by truth, which at first offends, which wins its way by degrees, which the many hate and would rejoice to crush.”

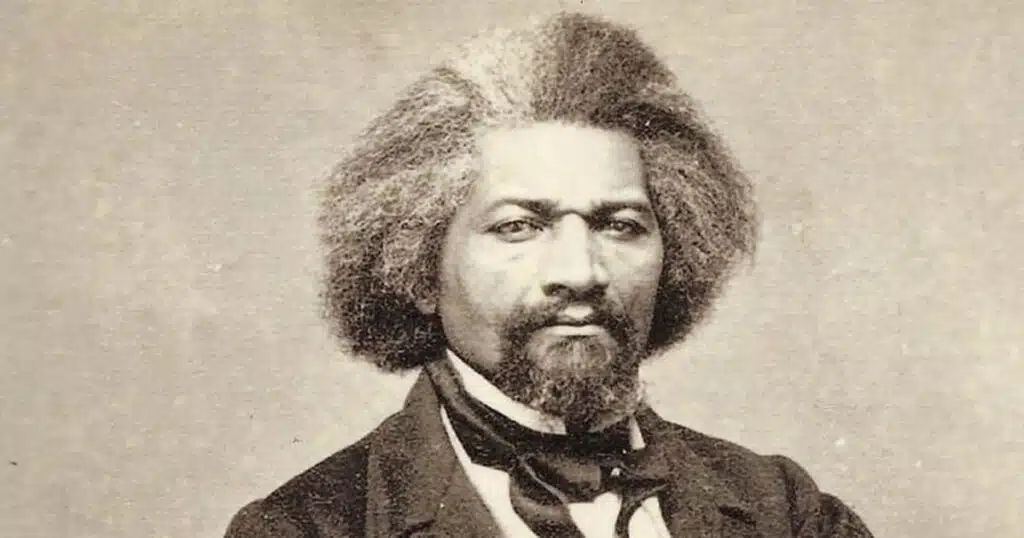

In his famous 1852 speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Frederick Douglass insisted that the constitutionality of slavery was a question for the people of the United States to debate. “I hold that every American citizen has a right to form an opinion … and to propagate that opinion, and to use all honorable means to make his opinion the prevailing one,” Douglass proclaimed. Without this right of free speech, Douglass said that “the liberty of an American citizen would be as insecure as that of a Frenchman.”

Eight years later, Douglass elaborated on these ideas even more forcefully. “No right was deemed by the fathers of the Government more sacred than the right of speech,” he said in Boston in 1860. “Liberty is meaningless where the right to utter one’s thoughts and opinions has ceased to exist. That, of all rights, is the dread of tyrants. It is the right which they first of all strike down. They know its power.” Douglass then added, “Slavery cannot tolerate free speech. Five years of its exercise would banish the auction block and break every chain in the South.”

The abolitionists understood that unpopular speech – not popular speech – is what needed constitutional protection. And as unpopular as they were in their time, they knew that if they could only be given a chance to be heard, their ideas could change the world.

This article was originally published by RealClearHistory and made available via RealClearWire.