The Federal Reserve’s Straight Jacket Tightens

There is something very strange going on in the financial markets, and it seems like it should be drawing far more attention than it has so far.

As the economy cooled, and inflation began to decline toward the Federal Reserve’s 2% target, Chairman Jerome Powell and the rest of the Fed’s board decided to move from restrictive to accommodative policy on interest rates. Since September 2024, the Fed has cut the federal funds rate, which is the interest rate banks charge each other for overnight transactions, three times for a total of 100 basis points or 1%.

In the past, interest rate cuts by the Fed were almost instantly reflected in the broader economy with savings accounts and loans following in tandem. However, in this rate cutting cycle, something unusual happened. While interest rates on income producing instruments such as CDs, savings accounts and bonds declined, rates on mortgages, auto loans and credit cards actually went up.

It’s really the worst of all worlds economically. Consumers are hit with a double whammy because the interest on their savings has declined while the interest on their credit cards has risen. Normally, businesses take advantage of lower rates to finance expansion, but in this instance, loans and debt have become more expensive.

So, what gives?

The Bond Vigilantes Return

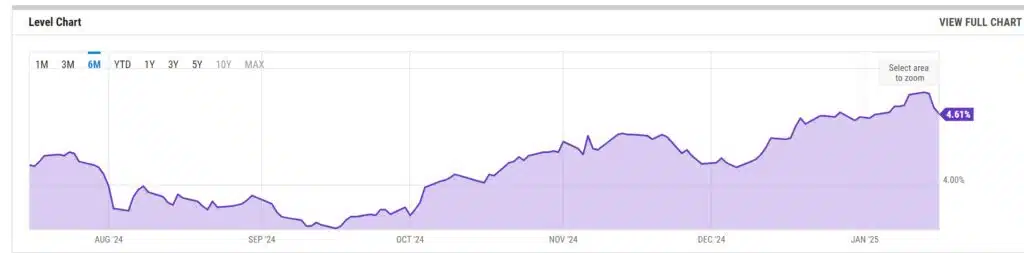

The key resistance to the Fed’s rate cuts comes primarily from the 10-year note, which is the benchmark treasury bond. As you can see from the chart below, almost simultaneous to the first cut in interest rates by the fed, the rate on the 10-year treasury began to rise in an inverse relationship.

It appears the issue is that bond traders, who base their purchasing decisions on how they envision the health of the economy going forward, believe there is some element or policy that is adding risk to U.S. government bonds.

These people are called the “bond vigilantes,” a term that originated in the 1980s and is attributed to economist Ed Yardeni. It refers to bond market investors who sell off bonds in response to fiscal or monetary policies they perceive as inflationary. This drives up bond rates and effectively punishes governments or central banks for what the investors see as irresponsible economic management.

So, why are the bond vigilantes refusing to purchase U.S. government bonds without a significant risk premium? It’s because they don’t believe the Fed will be able to cut the federal funds rate further, and they might actually have to raise rates in the future.

Naturally, legacy media wants to blame the rising yield on the 10-year on President Trump. The theory goes like this: Trump wants to impose stiff tariffs on countries like China, who export a substantial amount of raw materials and finished goods into the U.S. They reason these tariffs will result in higher prices for imported items and trigger a new round of inflation.

While this is the most elementary explanation and the easiest to sell the uninformed, it’s not really what is going on at all.

The True Reason No One Wants U.S. Bonds

The reality of the growing bond crisis stems from two areas: the Fed’s quantitative easing policy during the late 2000s and early 2010s coupled with ongoing irresponsible U.S. fiscal policy.

In order to stave off a severe recession/depression, the Fed aggressively initiated a program of buying distressed MBS, corporate bonds and treasuries in 2008 through 2014. This was called Quantitative Easing (QE). Remember, during the mid-2000s, interest rates were at historic lows. So, even though the Fed has been divesting itself of these assets to trim its balance sheet, it still has around $7 trillion of these low interest-bearing income securities.

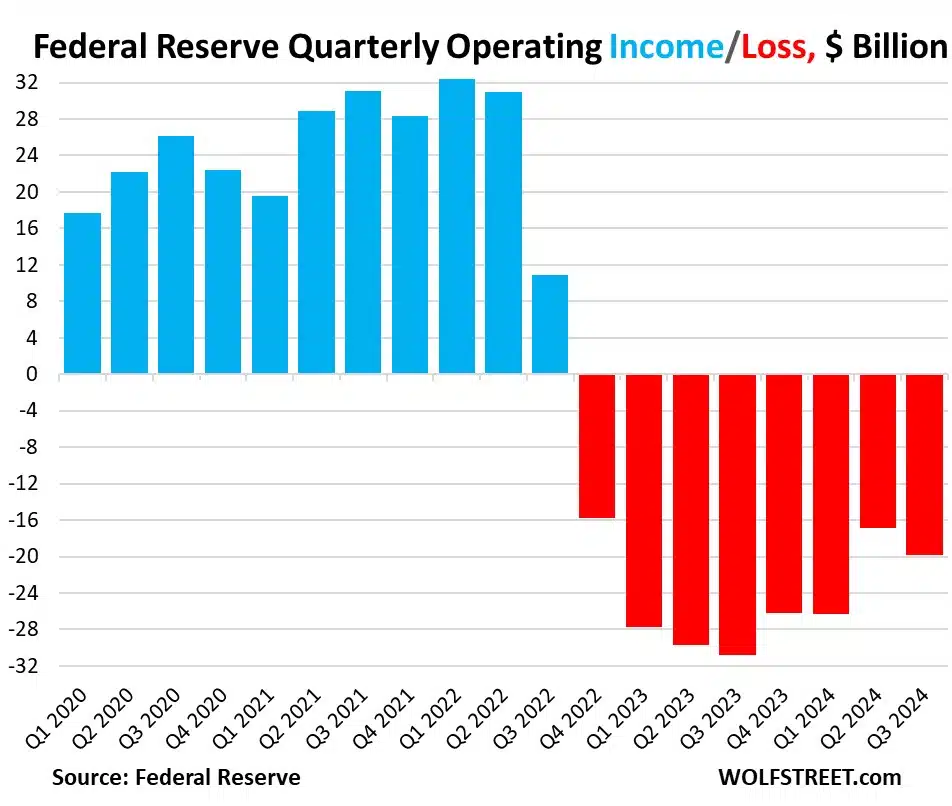

Meanwhile, they are currently being forced to pay prevailing interest rates, which are substantially higher than the mid-2000s, to banks that have deposits with the Fed and on money market funds. The combination of low interest on its assets and high interest on its liabilities has resulted in ongoing deficits. Instead of contributing $1.1 trillion to the Treasury Department as it did from 2008 to 2022, the Fed now has to print money to cover its losses since its balance sheet must zero out every year. From 2022 to present, the Fed has printed $210 billion in new money, which is highly inflationary and negatively impacts the value of existing dollars.

Meantime, the Treasury must make up for the loss of Fed income, so as an average, the Treasury Department has to issue an additional $78 billion in new treasury notes every year to cover the additional deficit.

When you add in the reality of a $36 trillion national debt whose maturing notes have to be refinanced regularly, along with new issues to cover the annual deficit, you begin to see the problem.

It’s a fiscal death spiral, and the bond vigilantes are way out in front of it.

Record treasury auctions of $85 billion on 1/7/2025 and $84 billion on 12/30/2024, are continuing to signal oversupply, and the selloff and weak demand coincided with the Federal Reserve interest rate cuts. Rising treasury yields have created a strong dollar, resulting in the devaluation of foreign currencies, and many central banks have had to intervene in the foreign market exchange to support their currencies. This typically involves liquidating reserves, including U.S. treasuries. In essence, traditional buyers have become sellers, which further amplifies the effect.

Storm Clouds are Brewing

While they may not know exactly why, many Americans have an unsettling feeling when it comes to the U.S. economy and for good reason. We are on an unsustainable path that only leads to one inevitable conclusion, and that is financial collapse. The fiscal death spiral already has its hands firmly around the neck of the American economy, and with more money printing, larger deficits and a national debt that is feeding on itself and could trigger a swift catastrophic collapse of the American economy.

Take heed and pay attention. This stuff is serious. If the deficit is not addressed quickly and inflation returns, get ready for hard times like we haven’t seen in a very long time.

If you want to see one possible outcome, research Greece in 2010.