The Four Last Things & Traditional Christianity: A View on the Death Penalty

You can hate the death penalty and at the same time acknowledge its divine justice in the divine order of a God whose commandments and mind have always confounded and challenged his creatures.

Just read the Torah and you’ll see how much he did for the Israelites while they continued to murmur and groan about it all. Just read what his people did to his Son.

The modern world, a world produced by a 20th century departure from all things traditional, a world I personally helped to create with my litany of mortal sins and loose living, recoils at the idea of capital punishment. Forgive me, reader, for my very real part in all of this.

Even many Catholics, including myself once upon a time, spoon-fed a steady diet of secular humanism, wince at the thought, believing themselves to be on the side of mercy and progress.

I even remember questioning the death penalty myself for a few years based on the high-sounding notion, “I don’t know if humans should be the deciding factor in whether or not a person lives.”

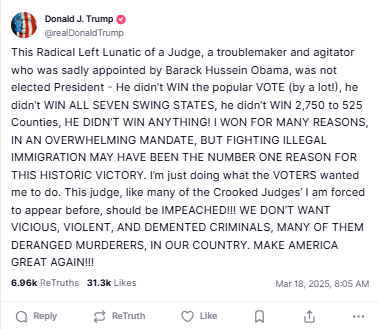

Even as I write this, I am thinking of the world I write about every day, which involves corrupt, George Soros-funded and Obama-appointed judges, one of which is actually in the middle of the deportation question at this very moment:

So the most poignant question I and I’m sure many others have is “What if an innocent person is sentenced to death by a corrupt judge bent on enforcing personal politics instead of the law?”

Part of my adherence to Tradition with this issue is a tribute to my wife, who won my heart in the courting stage when her answer to my question of what would be the greatest thing she could ever do was “to be a martyr for our Lord.”

She meant it, and I mean it when I say, I get it. I get that corrupt judges and a corrupt system can end the life of the innocent. But I can also say this: If I were ever wrongly convicted, I would actually rejoice. To be able to know the date and time of my death and be able to plead God’s mercy on my soul before it happens?

The greatest.

I think I feel this way because I have converted to Traditional Catholicism, which once taught and still teaches the Four Last Things the Faith once instructed the faithful to ponder for at least a few seconds every day: Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell.

I was 43 years old before I came across that for the first time.

I say all of that as a humble introduction to an incredibly sensitive issue, one that must be political, yes, but in my view, is more religious, one that puts the forgotten spotlight on these Four Last Things, on true sorrow, on true repentance, on true forgiveness, on eternal salvation.

Here’s the question we all could stand to ask:

What if the death penalty, rather than being an evil to be eradicated, is actually a divinely sanctioned means of both justice and mercy?

Louisiana In the Spotlight

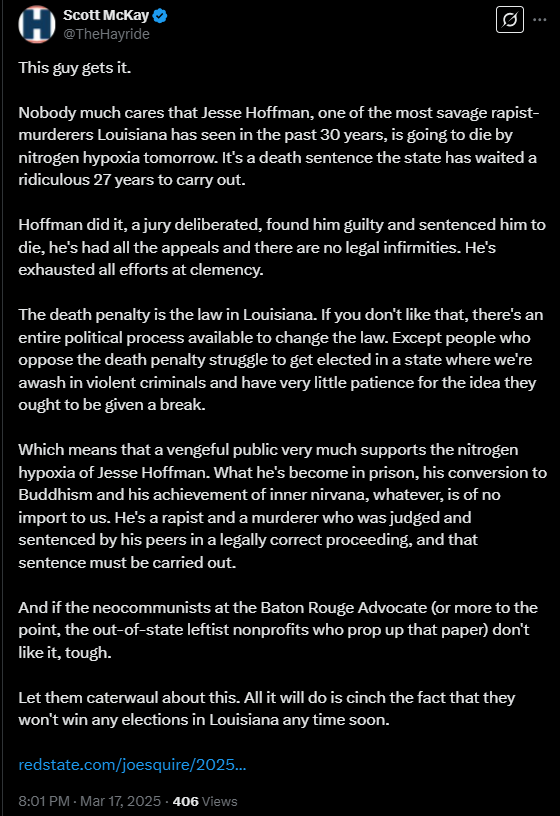

As just a brief digression to provide a local, political story attached to mine today, I was inspired by a desire to write on this for about a year now and Scott McKay’s column yesterday, which you can read here:

Scott followed that up with an X post. As always, I invite you to read the comments as well:

If I’m not mistaken he’s working on yet another today. His articles can work in conjunction with mine.

The Church’s Historical Stance

Like many today, I once saw the death penalty as a question of earthly mercy rather than divine justice. But the saints and doctors of the Church saw something deeper.

The Catholic Church, for most of its history until the mid-20th century, upheld the death penalty as not only permissible but, in some cases, necessary. The saints understood this. St Thomas More, as he awaited his own execution, acknowledged the just power of the state to take life when necessary. St Alphonsus Liguori taught that the death penalty is not only licit but necessary. And St Maximilian Kolbe, the martyr of Auschwitz, recognized that true justice must be ordered toward the eternal—not just the temporal.

It is an emphasis we personally witnessed as completely inverted during the Covid panic.

Innocent I (feast day March 25)—fifth century pope and saint–in his letter Ad Exsuperium, Episcopum Tolosanum, made it clear:

It must be remembered that power was granted by God, and to avenge crime the sword was permitted; he who carries out this vengeance is God’s minister (Romans 13:1–4). What motive have we for condemning a practice that all hold to be permitted by God? We uphold, therefore, what has been observed until now, in order not to alter the discipline and so that we may not appear to act contrary to God’s authority.

Not “it is allowed under certain circumstances.” Not “it is regrettable but sometimes necessary.” No—Innocent I declared it fully in accord with divine law.

Pope Pius XII of the 20th century before the Second Vatican Council said this:

Even in the case of the death penalty, the State does not dispose of the individual’s right to life. It is up to the public authority to deprive the condemned of the benefit of life in expiation for his guilt, after he has himself deprived himself of the right to live.

Here is St Thomas Aquinas, Church Doctor and its greatest theologian, recognized even by atheists for his persuasive powers:

It is written: “Wizards thou shalt not suffer to live” (Exodus 22:18); and: “In the morning I put to death all the wicked of the land” (Psalms 100:8). …

Every part is directed to the whole, as imperfect to perfect, wherefore every part exists naturally for the sake of the whole. For this reason we see that if the health of the whole human body demands the excision of a member, because it became putrid or infectious to the other members, it would be both praiseworthy and healthful to have it cut away. Now every individual person is related to the entire society as a part to the whole. Therefore if a man be dangerous and infectious to the community, on account of some sin, it is praiseworthy and healthful that he be killed in order to safeguard the common good, since “a little leaven corrupteth the whole lump” (1 Corinthians 5:6). —Summa Theologiae, II, II, q. 64, art. 2

The fact that the evil ones, as long as they live, can be corrected from their errors does not prohibit that they may be justly executed, for the danger which threatens from their way of life is greater and more certain than the good which may be expected from their improvement.

They also have at that critical point of death the opportunity to be converted to God through repentance. And if they are so obstinate that even at the point of death their heart does not draw back from malice, it is possible to make a quite probable judgment that they would never come away from evil.” —Summa contra gentiles, Book III, chapter 146

And here is St Augustine, another great Doctor of the Church, in The City of God:

The same divine authority that forbids the killing of a human being establishes certain exceptions, as when God authorizes killing by a general law or when He gives an explicit commission to an individual for a limited time.

The agent who executes the killing does not commit homicide; he is an instrument as is the sword with which he cuts. Therefore, it is in no way contrary to the commandment, ‘Thou shalt not kill’ to wage war at God’s bidding, or for the representatives of public authority to put criminals to death, according to the law, that is, the will of the most just reason.

Praiseworthy. Healthful. A positive good, not merely a tolerated necessity. Why? Because the execution of a criminal does not violate his dignity—it acknowledges it. A rational being, made in the image of God, is responsible for his actions and subject to just consequences.

God is a God of order. And yes, that order must include his mercy.

The evidence for this stance is abundant and consistent for the Church’s 2000-year history, until so much changed in the mid-1900s:

Though no Catholic is obliged to support the use of the death penalty in practice (and not all of the undersigned do support its use), to teach that capital punishment is always and intrinsically evil would contradict Scripture.

In just a couple of generations’ time, we’ve watched as Church leaders—most notably Pope Francis—have attempted to declare capital punishment inadmissible, as if centuries of teaching and divine law could be overruled with the stroke of a pen.

The problem isn’t just that recent seeming changes contradict the consistent teaching of the Church through the centuries. The problem, a cognitively dissonant one for the human mind, is that these changes inherently contradict reality– if the death penalty is, as St Augustine called it, “a means of protecting the innocent,” then what does it mean when a pope suddenly speaks otherwise?

Here it is paramount to keep in mind that there is a vast misconception out there, that every time the pope speaks he is speaking infallibly. This is simply not true, especially, especially, when the words contradict millennia of Church teaching.

Understand–I say all of this with respect and in fear and trembling as St Paul puts it in his letter to the Phillippians 2:12. I am not attacking Jorge Bergoglio, Pope Francis, something with which I’ve realized I need to make clearer if I do discuss him. My heart is protecting the heritage of our Church, the words of popes and saints that have come and gone before us. If we don’t at least talk about Francis’s deviating stances, then clearly we are showing disrespect to them—to those who have held the same title.

Did the nature of justice change in the 1960s? Did the criminal’s responsibility and burden of justice suddenly vanish? Did human nature itself undergo an overnight transformation after centuries of Church teaching based on the Bible itself?

What we’re witnessing—and this is chillingly clear as I read papal encyclical after papal encyclical from the 1700s on–is a deliberate shift away from Catholic tradition in favor of a modernist, sentimentalist approach that prioritizes earthly comfort over eternal salvation. It is absolutely infiltration of the most sinister kind, akin to what we all recognize inside America and seemingly every other government on the planet, something you all know I follow religiously. And that liberal shift has consequences—not only in the abstract realm of theology, but more importantly—eternally so–in the very real question of whether souls are being saved or lost.

It is a way of thinking and a posture of life that our panic over the pLandemic proved is long gone.

It is a way of thinking and a posture of life that ad orientum of the Traditional Mass has positioned inside me. When I face the East—when I face God the Creator and the direction from which Christ will return—while I worship, and not my brethren as beautiful as the creature is, my soul reorients itself to something very concrete, something of eternal consequence—

The Four Last Things.

The Finality of Death & the Power of Repentance

Let’s talk about the souls of the condemned. Because ultimately, this is about salvation, which I bolded above in the St Thomas Aquinas pull.

One of the strongest arguments in favor of capital punishment is one that few people want to discuss: the reality that the prospect of imminent death compels many criminals to repent.

And that is, if you take anything with you from this article, my most central point today.

That is the real heart of the matter.

This all has to do with reminding us of the Four Last Things when something like Covid proves that too many people are clinging to this life over the next.

Dr Taylor Marshall and his guest talk about this specifically along the lines of statistics in the video I’ll link below.

If you know that your execution date is set and that your time on this earth is truly limited, you are far more likely to think seriously about the state of your soul. It is no coincidence that criminals facing imminent execution are far more likely to repent than those serving life sentences. Death has a way of stripping away illusion. The condemned man has no more distractions, no more appeals, no more false hopes. He knows he will meet his Maker.

And that, ironically, is often what finally pushes him to seek confession, to receive last rites, and—perhaps for the first time in his life—to take eternity seriously.

Contrast that with the man sentenced to life in prison, perhaps even without parole. He always has tomorrow. There’s always another appeal, another chance, another possibility of release by a corrupt system or a corrupt judge or a new corrupt law passed by compromised legislators. He clings to this life and this world, not the next as Christ himself taught. He does not face the urgency of repentance because he is never truly confronted with the finality of death.

As long as there is a chance to extend this earthly existence, the urgency remains latent.

This is why the death penalty, far from being cruel, is often the greatest mercy. It forces the soul to reckon with its eternal fate. It strips away the false hope of a second chance in this world and redirects the focus to what actually matters: the next.

The condemned man who repents and receives the sacraments before execution is infinitely better off than the one who dies in his cell after decades of unrepentant sin.

And as I’ve already spotlighted, sympathy for the murderer is fine—but it has to be placed in the scope of eternity. If you really feel sorry for the convicted felon, consider where they would spend eternity if they never repent.

Christ himself told us hell exists and that there are souls there. Christ himself told us the way to heaven is narrow.

Frightening, but at least he told us the truth.

Here’s where the Church should be standing firm. Instead of aligning with the activists protesting outside Angola Prison, it should be emphasizing exactly what capital punishment provides: not only justice for the innocent but a sobering reminder to the guilty that their time is short and that eternity is real.

With respect, Pope Francis’s attempt to declare the death penalty inadmissible is not just an attack on Catholic doctrine—it’s an attack on justice itself. It is an attempt to rewrite moral theology in the name of modern sentimentality, a rejection of what so many popes, theologians, and saints have taught.

And it ignores one critical fact: Christ himself acknowledged the legitimacy of capital punishment.

As St Vincent of Lerins taught, true development of doctrine means deepening our understanding—not contradicting what came before. If something was true in the past, it remains true today. Otherwise, the Church would be admitting that it had been wrong for two thousand years.

Fr Thomas Petri, OP, furthers the point:

The death penalty is not an intrinsic evil. If a pope were to say otherwise, he would be in direct contradiction with two millennia of Church teaching.

Dr Taylor Marshall, in his podcast breaking down the 2018 Catechism change, summed it up well if you are Catholic and believe our religion has direct lineage to the apostles and Acts:

If Pope Francis’ change to the Catechism is a doctrinal development, then it would mean the Church taught error for two thousand years. And that is impossible.

In John 19:11, Jesus tells Pilate, “You would have no power over me if it were not given to you from above.” He does not deny Pilate’s authority to execute; rather, he acknowledges that such authority comes from God. Similarly, when the Good Thief on the cross accepts his punishment, Christ does not rebuke him—he rewards his repentance with paradise.

If Christ himself affirms earthly authority (as simply a means to a greater eternal end, of course), why do we suddenly think we know better? Did Christ cling to this life? Which thief got smug with Christ on the cross and said, “If you are the Christ, save yourself and us.”

Do we see that “save” here means to “save” here on earth? Do we see the difference in what “save” means when it comes to what Christ says to the Good Thief?

Again, think back to what we were clinging to with Covid. If people clung desperately to this life during Covid at the expense of eternal truths, is it any surprise that we now reject the most sobering reminder of the life to come?

LEJEUNE RELATED

Incidentally, that Good Thief—St Dismas—is celebrated on March 25, the same date as Innocent I’s feast day, the same date as my wife’s birthday, the same date as the great feast of the Annunciation—the first mystery of the Joyful Mysteries of the Rosary. It is when the angel Gabriel came to Mary and announced that she would conceive by the Holy Ghost. It was when God himself became Incarnate to come to save anyone who would come to him in repentance.

What an appropriate mystery to contemplate when it comes to the blessing of capital punishment to the condemned man in need of that incarnate Savior.

The question, then, is not whether the Church can abolish the death penalty. The question is whether it will remain faithful to its own teachings or continue down the road of moral revisionism, relativism, liberalism.

The modernism Pope Pius X so warned against.

The modern world loves to pit mercy against justice, as if the two are locked in a cosmic cage match as eternal opposites. It is yet another prime example of why I argue against the binary trap so much in my work. It’s a trap even attempted on Christ. But true mercy does not negate justice—it fulfills it. It is why Christ said not one tittle of the Law—the Old Testament—was being abolished through him, but fulfilled instead (Matthew 5:18).

If a condemned criminal is more likely to face his sins and repent when he knows his execution date, are we truly acting mercifully by keeping him alive in a prison cell, giving him every excuse to delay his conversion?

These are not comfortable questions. But they are necessary ones.

None of this is about politics, even though yes we must talk about it in a political space because of what America is. It’s not even about what makes us feel good.

It’s about what is true. And for Catholics, the death penalty has always been a part of Catholic teaching. The passing of two generations, even though I understand all of us live inside recency bias, does not change that.

Capital punishment is not merely about punishing crime. It’s about justice. It’s about restoring order. It’s about protecting the innocent. And yes—it’s about mercy too, about saving souls.

Even those of the condemned.

—

May everyone named directly or referenced indirectly ask forgiveness and do penance for their sins against America and God. I fight this information war in the spirit of justice and love for the innocent, but I have been reminded of the need for mercy and prayers for our enemies. I am a sinner in need of redemption as well after all, for my sins are many. In the words of Jesus Christ himself, Lord forgive us all, for we know not what we do.