Another Thing Folks Like About the South: Public Education’s Revival

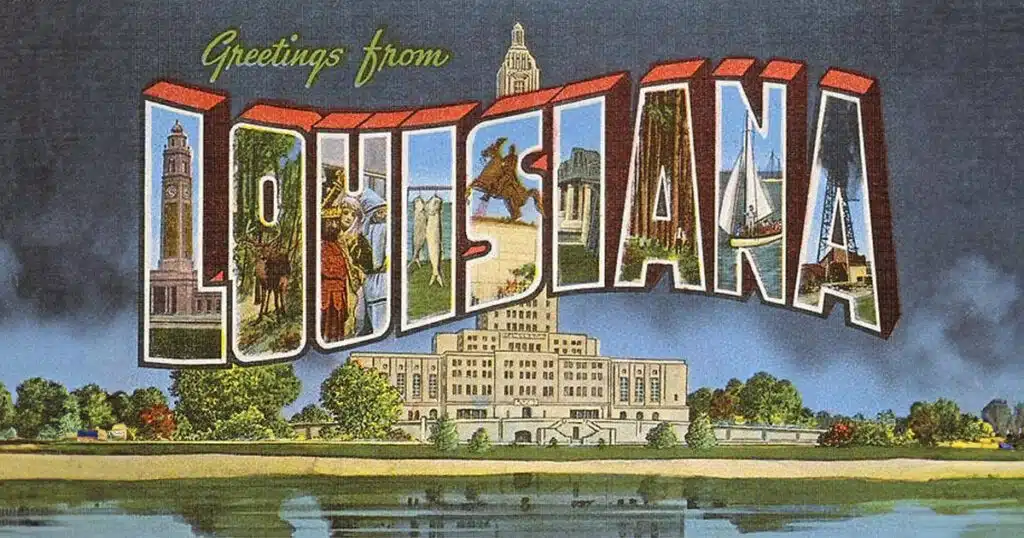

GEO Prep Mid-City Academy, located in one of the poorest sections of Louisiana, did something almost unheard of in public education – it went from dying to thriving in just a few years.

The Baton Rouge K-8 school, which is almost entirely filled with disadvantaged black students drawn from a lottery, repeatedly received a failing grade until new leadership took over in 2017. It steadily improved and landed in the top third statewide in reading proficiency last year, not by following newfangled pedagogical trends but by focusing intensely on the basics of learning: a proven curriculum, teachers trained to master it, and testing to hold everyone accountable for progress.

“We are just completely devoted to academic achievement,” said Kevin Teasley, the head of GEO Academies. “We don’t chase fads like a lot of schools. My inbox is full of them. Our success comes from our repetitive and long-term commitment to getting results.”

Mid-City is emblematic of the surprising public school revival in a handful of mostly southern states, with Louisiana and Mississippi leading the way. Over more than a decade, these two states have skyrocketed from the very bottom to near the top in the rankings of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the gold standard of proficiency tests. As public education sinks deeper into a crisis of low performance and high absenteeism, the southern states are demonstrating how schools can significantly lift student achievement.

Louisiana and Mississippi’s rise is all the more improbable because they are the two poorest states in the nation, a condition that researchers trace to the particularly deep penetration of slavery in their economies and their subsequent anti-union laws that have suppressed wages. Not surprisingly, both states are in the bottom quartile in public education spending, suggesting that better schools aren’t just a matter of funding. Both also have relatively weak teachers’ unions that typically oppose the kinds of reforms that are driving up proficiency scores in the two states.

The question is whether this reform movement, dubbed the Southern Surge, can break out of its niche and expand into more liberal states in the Northeast and West to make a bigger national splash. There are reasons for doubt. States like New York and Washington, with powerful teachers’ unions, have moved in the opposite direction, tamping down rigor, such as testing for graduation and accelerated programs, to achieve “equity” for disadvantaged students. They see accountability through testing as part of the problem.

“Southern states have seized on a political environment that allows them to do the things that matter,” said Rick Hess, director of education policy at the American Enterprise Institute. “These states have weaker teachers’ unions and Republican dominated political cultures. To drive improvement, it’s easier if you have the politics of Mississippi than the politics of Massachusetts.

Pushing Literacy Reform

Following the South, most states have passed laws promoting what’s popularly called the science of reading, or phonics-based curricula, that’s been repeatedly shown to improve literacy. The intent is to boost reading proficiency in the crucial early elementary grades, which largely determines whether students succeed in later years. But enacting new laws has been the easy part of reading reform, and they appear to be little more than window dressing in many states because of the heated politics around classroom practices.

Local school districts have considerable control over what goes on inside classrooms and are skeptical of state interference, while unions guard teacher autonomy as a top priority. In Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee, it took many years to persuade districts to replace a mishmash of ineffective reading curricula with content backed by research that was vetted by the states. Just as important, teachers had to undergo intensive training to understand the many components of the science of reading since university programs haven’t kept pace with changing classroom practices and don’t adequately cover it.

Even more controversial, states had to toughen their lackluster accountability systems, the main driver of progress in the South. By grading schools on the number of students who are proficient and rapidly advancing toward that mark rather than on lenient measures like attendance, southern states, including Tennessee, are identifying the low performers and fixing them.

“Literacy reform doesn’t work without strong accountability,” said Lizzette Reynolds, the education commissioner in Tennessee, which strengthened its accountability system in 2023. “Without understanding the data and knowing how school districts are doing with their students, we wouldn’t see the improvements that we have made.”

The southern states were able to work around political resistance to the literacy overhaul, but it will be a bigger obstacle as the movement inches into Democratic territory. In Michigan, for instance, Democrats ended the state’s accountability program in 2023 that identified poor-performing schools with A-F grades, opting for a more forgiving approach. The following year, the state’s early reading proficiency score continued declining to near the bottom of the national rankings.

Still, some blue states, including Colorado, are adopting parts of the playbook, with Maryland the most noteworthy example. Carey Wright, who led Mississippi’s dramatic turnaround, now aims for a repeat performance as the superintendent in Maryland. Wright told RealClearInvestigations that she expects to see more blue and red states join the reform movement that she helped inspire.

“States are mirroring a lot of the things that we did in Mississippi because it’s been successful,” Wright said. “We used approaches based on research showing they work and that’s why I feel strongly about what we did.”

The Trump administration’s dismantling of the U.S. Department of Education cuts both ways when it comes to reading reform. Southern officials are concerned about the gutting of federal research since it has played an important role in discovering effective educational approaches, including the science of reading. In Mississippi, Wright says, the department supported research into how classroom practices were changing as part of its reforms, confirming that the state was on the right track.

If, on the other hand, the federal government gives states more authority over spending Title 1 funding for disadvantaged students by converting it to block grants, that could help advance the reforms. “We have proven our ability to drive results forward and I think we can accelerate those outcomes with less influence from Washington, D.C.,” Cade Brumley, the state superintendent in Louisiana, told RCI. “We could better address the exact needs in our state without any federal strings attached.”

Origins of Accountability

The 2024 NAEP scores released in January confirmed once again that public education is broken. In the key benchmark of fourth-grade reading, the average score has been steadily dropping for more than a decade, and last year matched the all-time low of 1992, with only 31% of students reaching proficiency and the gap between the top and bottom performers expanding.

The differences in state performance also matter, suggesting that the southern playbook is part of the explanation. Massachusetts, which has long held the title as the top-performing state, suffered a 10-percentage-point drop in fourth-grade reading proficiency to 40% of students from 2011 to 2024. New Jersey, the former No. 2 state, also fell sharply. Both states have a weak set of literacy interventions and less robust accountability compared with Louisiana and Mississippi, according to an analysis by ExcelinEd, an advocacy group.

With 38 states declining in early literacy in that time span, the dramatic rise of the two southern states is extraordinary. They were dead last in the 2011 rankings. In Mississippi, proficiency jumped by 10 percentage points to 32% by 2024, the most growth of any state. It’s now 10th in the nation, far ahead of states like New York that spend more per student. What’s more, Mississippi climbs to first place in reading proficiency when adjusted for differences in state poverty levels in an Urban Institute ranking. Louisiana’s growth was a close second to Mississippi and lands in second place, according to the adjusted list.

The southern revival has its roots in the bipartisan No Child Left Behind Act signed by President George W. Bush in 2002. Initially backed by governors, the act required states to get serious about holding schools accountable for lifting proficiency, with consequences such as closure for repeatedly failing to improve. Fourth-grade literacy scores shot up significantly during the next decade, particularly for black and Latino students.

But over time, states objected to the ambition and rigidity of the act and were allowed by the Obama administration to redesign accountability systems to meet their particular needs. Rather than emphasizing proficiency, states in 2011 began using easier measures to evaluate schools. Fewer schools were identified as needing improvement, and states had more leeway in how to fix them, while consequences for failure were eliminated.

It hasn’t worked in most states. The weakening of accountability, which was later wrapped into Obama’s Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), coincided with the drop in NAEP scores from 2011 through 2024 – a falloff that likely has several causes, including the proliferation of smartphones and social media. A Government Accounting Office investigation last year found that most states weren’t even complying with ESSA’s relaxed accountability rules.

“The school improvement efforts are now tepid at best,” said Charles Barone, who has played a central role in shaping federal education reforms including No Child Left Behind. “States are not doing much to help students attain proficiency.”

Louisiana Finds Its Stride

Louisiana and Mississippi, on the other hand, remained committed to sweeping changes. They wanted to shed their reputation for running the worst schools in the country and hired dynamic reformers – John White in Louisiana and Carey Wright in Mississippi – who broke the mold of bureaucratic-minded superintendents typical in education departments.

“Our educational system can’t change at scale without the leader, the state, asserting a view on how it should change, and using its many tools including accountability to make it happen,” White, now CEO of curriculum developer Great Minds, told RCI. “The history of many states not having a view at all, and not doing their job, is the problem.”

White’s early focus on research-backed curricula was, in the words of author and expert Robert Pondiscio, “the last, best, and almost entirely un-pulled education-reform lever.” White, a savvy coalition builder and former teacher, turned to veteran instructors to identify the best curricula and successfully incentivized districts to deploy them. White’s progress came despite constant attacks from Louisiana’s biggest teachers’ unions and a politically ambitious governor who turned against him over the superintendent’s embrace of higher Common Core standards that informed the teaching materials.

White left his post after eight sometimes bruising years. In 2020, Superintendent Brumley took over and has backed several reforms that built on White’s accomplishments. The next year, Louisiana required that all K-3 teachers undergo about 50 hours of training since new curricula wouldn’t help much if they didn’t have the confidence to use them. By 2022, Louisiana’s fourth-grade literacy scores began their ascent.

Like White, Brumley hasn’t steered clear of controversy. Starting in the current school year, third graders who score well below proficiency in reading won’t be promoted to fourth grade and will receive intensive tutoring. The end of social promotion stirred much debate among state lawmakers because it disproportionately affects black students. But the retention policy that Tennessee and Alabama also adopted has a track record, significantly improving the reading performance of students in Mississippi.

Brumley is only getting started. A stronger accountability system that raises the academic bar begins this fall in Louisiana, joining Mississippi and Tennessee in assigning clear and more credible A-F grades to schools to improve their performance. Brumley says that the old system obscured results and was too soft, with almost 90% of schools getting an A or B for academic growth, even though students weren’t advancing very much toward proficiency.

The new K-8 system, which associations of teachers and superintendents opposed because of its reliance on testing, makes it more challenging for schools to get a high mark. Half of the grade will be based on student academic growth, but they will have to advance more rapidly for a school to be awarded points. The other half is derived from the number of students who reach proficiency. Schools no longer get points for students who approach it.

“In Louisiana and across the country, establishment groups are trying to restrict reform, so it’s important that leaders continue to push against the status quo,” Brumley said. “Sometimes that comes with taking shots and daggers, but it’s worth it if it prompts the academic growth of students.”

Blue States Motivated to Reform

The obstacles reformers have faced in the South may seem like child’s play in blue states, where teachers’ unions have considerable clout in shaping legislation. The California Teachers Association, so far, has prevented lawmakers from passing a law to mandate the science of reading. But a continuing decline in NAEP rankings, potentially hurting states’ ability to keep residents from leaving and grow businesses that need skilled workers, may be a catalyst for change.

“There are a lot of traditionally higher performing states that have seen declines in performance as others catch up, so they are going to see the need to do something different,” said Christy Hovanetz, a senior policy fellow at ExcelinEd who advises states on improving accountability. “This is exactly what started the reforms across the South.”

Democrat-led Maryland is a case in point. It was a high flyer, the 3rd best state in early literacy in 2011, before plunging to 42nd by 2022. It was time for a change in the person of Carey Wright, who had recently left Mississippi on a high note. The superintendent has even more ambitious plans for Maryland.

Drawing from the playbook Wright helped author, Maryland approved several early literacy reforms that are now being rolled out in classrooms and raised academic standards across all subjects. Last year, the state’s fourth-grade literacy score rose for the first time in seven years, spurring the board to declare its goal for Maryland to rank in the top 10 by 2027.

Wright is now pushing into the next frontier of reform – lifting math achievement after a precipitous fall since 2019. In January, the Maryland state board approved an overhaul of math education with more accelerated instruction for advanced students, customized interventions for low performers, and a required number of minutes devoted to the subject.

Wright has a talent for making partners out of potential opponents. Although Maryland has a strong teachers’ union, Wright says they have a good relationship partly because it was given a seat at the table to design a more rigorous accountability system to start in 2026. “They have a lot of questions, no doubt,” Wright said. “In Maryland you have to bring along your stakeholders because the politics are very different here than in Mississippi.”

Several other blue states are also pushing literacy reform. It’s taken Colorado more than a decade to get phonics-based curricula into classrooms, and now the state is making progress on a better accountability system. Its national ranking has risen 12 notches to 6th place last year.

In Virginia, the plunge from 9th place to 32nd in the rankings turned Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin into a crusader for reform. In the old system, Youngkin told the media, 89% of schools received full accreditation, even though 66% of K-8 grade students failed or nearly failed math and reading assessments. Virginia’s new system, while not as strong in stressing proficiency as Louisiana’s, is set to begin this fall. Democrats support it but are pushing for more funding to help schools improve that are graded “Off Track” or worse.

“Virginia’s new system is far better,” said Hovanetz of ExcelinEd, who talked with state leaders about the reform. “They were one of the states with the lowest expectations of proficiency.”

While reformers see more progress ahead in blue states like Rhode Island and Connecticut, there is also backpedaling. Florida, once a leader in the movement, seems to have lost its mojo. Its big drop in early literacy last year stirred much soul searching.

Florida Commissioner Manny Diaz accused NAEP of using a flawed methodology, saying the sample of test takers didn’t include high-performing students in school choice programs who were getting a private education. Some reformers see a different problem, arguing that Florida has been distracted by fighting high-profile battles over woke textbooks and the gender of bathrooms to the detriment of a keen focus on proficiency.

“I can’t speak for Florida,” said Wright of Maryland. “But in this work, you can never lift your foot off the pedal. This is relentless. Day in, day out, you have to look at data and never assume that things are going to get better.”

This article was originally published by RealClearInvestigations and made available via RealClearWire.