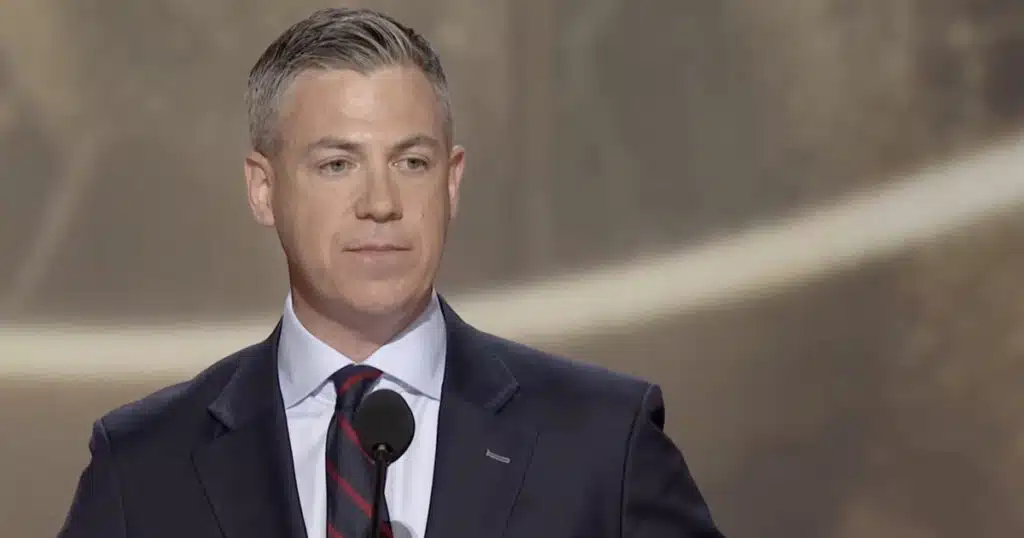

Jim Banks: A Trade Warrior After Trump’s Own Heart

Sen. Jim Banks was uncharacteristically curt.

The Indiana Republican was walking to the elevator last month when a fired federal employee caught up to him on Capitol Hill. The protester, a budget analyst who had received a pink slip from the Trump administration like thousands of other government employees, demanded an answer for the ongoing mass layoffs. If he was looking for sympathy, he picked poorly.

“You probably deserved it,” Sen. Banks said.

“Wow. That’s great to hear,” the startled bureaucrat stuttered. “Why did I deserve it?”

As the doors slid closed, a sly smile on his face, he replied, “Because you seem like a clown.”

The opposite of Hoosier hospitality, it was closer to righteous indignation – and it prompted swift and opposing reactions: chortling from conservatives, indignation from liberals. “The left accuses me of not being empathetic,” the relatively soft-spoken Banks tells RealClearPolitics of the exchange, “but that just can’t be farther from the truth.”

He watched as cuts to the federal workforce earned wall-to-wall media coverage and listened as some of his new colleagues likened reductions in the public payroll to an assault on democracy itself. He felt caught between “two different universes.”

While government employees inside the Beltway are treated like a protected class, blue-collar workers from flyover country are viewed as victims of inevitable “progress,” or more often, not viewed at all, he says. The workers at shuttered factories seldom go viral, Banks notes: “There was no sympathy for them.”

And that is what really bothered Banks. “I wasn’t trying to be funny, and I wasn’t looking for a viral moment,” he says. “I just have no patience for anyone who thinks they’re entitled to a government job.”

The other thing that bothers Banks came to him a week later while seated in the White House Rose Garden: the ignorance, or indifference, of the politicians who signed the trade deals that he believes hollowed out the heartland. The president said the same on “Liberation Day.”

“It is so true,” Banks insists. “After eight years in Washington, I’ve come to recognize that President Trump is right. That’s why I fully back the tariffs.”

Hence his ongoing bet. Banks doesn’t merely believe tariffs will make middle America boom. He is convinced that if Republicans embrace the working class, if they cast their lot with the calloused rather than the credentialed class, the GOP can cement permanent majorities. This makes the 45-year-old senator a trade warrior after Trump’s own heart.

And that trade war has been going pretty well for Indiana. So far.

Rather than build the new Civic in Mexico as planned, Japanese automaker Honda will build the popular sedans at their Greensburg plant to skirt the 25% auto tariff. General Motors expanded its light truck production for the same reason, and now more Chevy Silverados and GMC Sierras will roll off the line in Fort Wayne. But it is more than just cars and trucks. Under the threat of tariffs, Pharma giant Eli Lilly beefed up domestic production and hurried plans for a $9 billion research and manufacturing facility in the state. Swiss drugmaker Novartis has followed suit and will expand production in Indianapolis.

Banks keeps a running list of every new factory expansion and each new investment from cardboard boxes to kid bicycles in Indiana. “We have got everything going for us, the workforce and the manufacturing base, already,” he says. “We’re going to benefit more than anywhere in the country.”

While Indiana already has the most manufacturing per capita of any other state, he believes they have even more to gain from tariffs. Most economists say otherwise. Because the state is so manufacturing-heavy already, it has the most to lose on both sides of the export-import ledger.

Manufacturers who rely on foreign inputs such as raw steel and finished semiconductors will likely take a hit. “It’s going to raise their costs, and it’s going to lower their productivity,” predicted David Hummels, an economics professor at Purdue University.

Trading partners aren’t powerless either. They know the pain points to target for retaliation (think corn, soybeans, and pork). “Indiana is easily the most trade exposed state in the union,” said Michael Hicks, the director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University. “We are ground zero for both agriculture and manufacturing.”

And while the White House touts the benefit of “strategic uncertainty” in overseas trade talks, that same uncertainty throws investors for a loop at home. “We are probably in a recession already,” said Kyle Anderson, an economics professor at the Indiana University Kelly School of Business. Firms are holding their breath and hoarding cash as negotiations continue. If those talks fall through, if the Liberation Day tariffs go live, he concluded, “we’re looking at severe contraction in the economy.”

Such is the conclusion of a century of economic consensus applied to the current trade wars. But Banks scoffs at that “foolish outlook on what President Trump is doing.” The tariff schedule announced by the president in the Rose Garden isn’t the new status quo. It’s simply the starting point for negotiations. “Deals are going to happen quickly,” he predicts, “and they’re going to be really good deals for America.”

Banks doesn’t have much patience for economists in air-conditioned faculty lounges anyway. Many of those same dismal scientists heralded globalism as an unmitigated good. “This is about the long-term viability of blue-collar jobs and America’s manufacturing base,” he says. “And for too long we’ve had leaders, and university economists, who turn a blind eye to what China has done to us.”

Patrons of big business for decades, Republicans once held as articles of faith that greed was good, global markets were most efficient, and Wall Street knows best. But not Jim Banks, and not the current populist president and his anti-free trade adherents who have taken to insisting that unfettered commercialism makes a poor substitute for the American Dream. Markets are made for America, they argue, not America for markets.

This vision isn’t just a protectionist fever dream. The discontent is real.

“We built our entire economic foundation on consumerism, providing Americans with the cheapest products,” said Larry Fink, CEO of private equity behemoth BlackRock and no friend of MAGA, during a recent CNBC interview. “Did that come at a cost that some of our communities were decimated and lost jobs? Absolutely.” His conclusion? “Maybe we went too far on the consumerism.”

Workers who lived through the China shock had already reached their own conclusion decades before academics coined that term. And their answer isn’t that “maybe” globalism went too far. During his maiden speech, Banks said as much, condemning the system that allowed 6 million manufacturing jobs to go overseas while 90,000 factories shuttered. A bright spot in the Rust Belt, Indiana has survived these trends. They have not escaped them.

Yes, the state has more manufacturing per capita than the rest of the union. But Banks argued on the floor that wages haven’t kept up.

Yes, the state leads in domestic steel production. But he reminded his colleagues in the upper chamber that the industry has shrunk by two-thirds.

Yes, Indiana and America lead in advanced manufacturing. But Banks warned that those advantages are eroded daily by Chinese competitors who build industries off the backs of slave labor, scoff at copyright laws, and reverse engineer and then steal American technology.

A rite of passage in the Senate, Banks delivered his maiden speech the same day Trump announced a 90-day pause on most reciprocal tariffs. The markets, the president said, were getting “yippie.” But Banks was unbothered. It isn’t his first trade war.

“We went through this eight years ago, and I learned a lot of lessons. I didn’t always trust President Trump, and I was wrong. President Trump was right,” he says with the unwavering faith of a fervent convert. “I know where Hoosiers stand on all of it: They’re begging us to stand up to China and back President Trump’s America First trade agenda.”

Banks won a House seat in 2016 and arrived in Congress, by his own admission, as “a traditional conservative Republican.” He reflexively believed in free trade back then, disagreed with Trump on fiscal and foreign policy, too, and was rather unremarkable. At least, that is, according to an Atlantic profile which described the freshman as “a fairly ordinary Republican congressman, trying to find his way in Washington in not-so-ordinary times.” That was the beginning, though. Evolution was gradual.

A conscientious objector early on, Banks opposed Trump’s first trade war. Despite a veto threat, he co-sponsored legislation in 2019 that would restrict the president’s authority to levy tariffs. That’s when the phone calls started coming. One of the voices on the other line: the executives in the Nucor C-suite. They are the giants of the mini-mill, the company that makes skyscraper steel from scrap metal in Indiana.

“I quickly heard from Northeast Indiana, from Nucor and other steel leaders that came and educated me on why they supported, and they wanted me to support, the tariffs,” Banks says of those conversations. Complete conversion on the tariff question came later during COVID-19 when China restricted the export of medical necessities, like medical masks and ventilators. Products that the U.S. once produced stateside were now out of reach. The pandemic “exacerbated,” the argument, Banks says. He looks at his vote to claw back presidential tariff authority as “one of my few regrets from my time in Congress.”

Today, it seems like Republicans are all protectionists now. At least in public.

Virginia Democrat Rep. Don Beyer has watched the transformation from across the aisle. Off the House floor – read that: away from the cameras – he reports that his GOP colleagues are spooked. They don’t like the on-again, off-again tariffs. So why won’t they object? “It’s tough to stand up to Donald Trump,” Beyer told RCP, “and expect any kind of political career.” This doesn’t explain Banks, though.

His conversion isn’t recent. And yet he isn’t a conservative apostate either. Instead, Banks is of the new kind of Republicans, a Middle American radical who is rebellious only insofar as he rejects a century of economic consensus and an obsequious deference to big business. He exudes an intuitive kind of heartland conservatism. He inherited it.

Banks was new in town, still just that “fairly ordinary Republican congressman” that the Atlantic once described, when he attended a private reading of a new memoir called “Hillbilly Elegy.” Killing time before the author arrived at the Library of Congress, he struck up a conversation with “the wife of some liberal Senate Republican” (perhaps a sign of the times; moderate GOP senators are an increasingly rare breed). She had brought her well-worn copy and a sense of curiosity.

“I am excited to hear him speak,” she explained, “because I find these people to be just so interesting.” Banks smiled back politely, not wanting to stir up trouble. “Wait a minute,” he thought to himself as he took his seat, “these people,” the objects of zoological fascination in Washington, D.C, “are my people.”

A “hillbilly” just a generation removed, he grew up in a trailer at the end of a dead-end street. His father, a union Democrat, worked on the line building axels and driveshafts at a Columbia City plant. His mother had a job as a line cook. Toys branded “Made in China” were put back on the shelf at department stores, and in their home, “NAFTA was a four-letter word.” Despite the occasional furloughs, in the 1980s when his dad picked up graveyard shifts at other factories to make ends meet, there was opportunity in Indiana. His grandfather had moved there for work, leaving a Kentucky coal mine behind. His grandmother, illiterate, often barefoot, and the stuff of family legend, scandalized their small town when they arrived.

“We talk about growing up on the wrong side of the tracks,” Banks later told J.D. Vance in 2021 during a now-deleted episode of the Indiana congressman’s podcast. “And we are proud of it.”

Banks can only recall two politicians who truly appealed to his family. The first was Ross Perot, the fiercely anti-free-trade third-party candidate who helped cost President George H.W. Bush reelection in 1992. The second was the man who descended a golden escalator decades later and won the presidency the year Banks was elected to Congress. His father won’t admit it, but Banks is certain his dad “was more animated when Donald Trump won than when I did.”

Their inherited worldview wasn’t strictly ideological. At least at home, it was common sense. An appliance made in the USA outlasted the Chinese knock-off, and exporting an industrial base to an unfriendly communist regime had negative geopolitical externalities. “Most guys like my dad, who are wise but didn’t go to college, for them,” he says, “this is just intuitive.” It is now the basis of his ongoing mission.

On a flight from Fort Wayne to Indianapolis, Banks slid a two-page memo across the cabin table. Trump was two months into a four-year exile, and Republicans were in the wilderness. After the January 6, 2021, riot at the U.S. Capitol, some Republicans argued it was time to move on from the former president and his populist project. Argued former Wyoming Rep. Liz Cheney, the sixth-ranking House Republican, Trump was “an unrecoverable catastrophe.” But Banks called Trump’s populism, “a gift that didn’t come with a receipt.”

Banks believed that Republicans could either double down on blue-collar populism or kiss their hopes of winning the popular vote goodbye. McCarthy listened as Banks listed four priorities during the 30-minute flight to guide the party for the next three years: Hammer Biden on the border, condemn Democrats for their “woke” identity politics, condemn China’s “predatory trade practices,” and create a “working families task force.” Check, check, check, and check. The GOP would follow through on each of those bullet points.

The memo was the answer key to a question Banks would later ask Vance, years before he entered Ohio Republican politics: “How do we keep voters like my dad in the Republican Party?” Early returns were positive. Without Trump, Republicans barely won back the House of Representatives in the 2022 midterms. With Trump, they gained ground with every major demographic group and won back complete control of government. Questions still linger, however.

“Right now, these Trump voters – the GOP is just renting them,” longtime Trump pollster John McLaughlin told RCP of the new additions to the Republican voting coalition. Speaking of the disaffected Democrats and traditionally liberal constituencies who pulled the lever for Trump, he added that the GOP needed “to make a decision if they’re going to make them permanent.”

Banks has already made up his mind. “It’s a multiracial, union, across-the-board working-class voter coalition that gave President Trump his victory and gave us majorities in both the House and the Senate,” he says. “The new GOP has to stay cemented there.” Trump won’t be on the ballot during next year’s midterms or the general election after them. “How do you win?” he asks of the post-Trump era. “You win on that agenda.”

The effort is ongoing; the document that Banks wrote five years ago, a mile marker. While Republicans now love the tariff and the labor union, the change represents a sudden break with the past.

“Frankly, the fact that the memo that you wrote could be written by a sitting U.S. congressman and could be shared broadly in the conservative intellectual world,” Vance told Banks in 2021, “is a good sign.” It wouldn’t have been possible, and certainly wouldn’t have been taken seriously, before Trump. Added Vance, “I don’t think that would have happened five or 10 years ago.”

Republicans have been soul-searching for the better part of a decade. Former Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, not unlike Banks, hit the books after losing the 2016 nomination to Trump to try and discover why the GOP base had just rejected a GOP orthodoxy. Overtures to free trade, limited government, and a muscular foreign policy fell flat when compared to whatever the billionaire celebrity was offering. The old answers couldn’t solve “American carnage.” A new right, these reform-minded conservatives have concluded, is required.

But Banks struggled with the nomenclature. “I’m not big on the terminology. I like common-good capitalism,” he told Vance of the term that Rubio favored at the time. Others called the new orientation Trumpism, nationalism, populism, or national populism. “Help us out,” he asked. “What is it?”

“Populism by itself is not enough,” the “Hillbilly” author replied.

“You need populism along with really high-quality leaders,” he continued.

“The biggest problem right now in America is not the populace, the population is not the problem,” he concluded. “The leaders are actually the problem.”

Vance presented himself as the solution the next year and ran for Senate. His first endorsement from a member of Congress came from Banks. It wouldn’t be the last time. He says unequivocally that now Vice President Vance “is going to be our nominee in 2028.” More than horse trading, the men with similar backgrounds have a genuine friendship.

At a Fort Wayne rally last summer, Vance paused to ask the Hoosier crowd for help finding “Jim’s Dad.” The congressman spoke “highly of his family,” he said to explain the interruption of regularly scheduled campaign programming. Vance wanted to meet before hopping back on the plane. “Let’s shake hands afterwards at least,” he said while searching through the crowd, “so I can tell Jim we met properly.”

Opportunity for Banks came during the Trump exile. As chairman of the Republican Study Committee in June of 2021, he led a pilgrimage to Trump’s club in Bedminster, New Jersey, where lawmakers workshopped the messaging of the working-class party at the luxury estate. The two men didn’t know each other well. During Trump’s first term, Banks was closer to former Vice President Mike Pence.

Banks met the president in the Oval Office after standing in a long line of newly elected members of Congress. A photo was customary, but the Indiana Republican had a special request. Could the vice president join the picture? Trump agreed. Behind the Resolute Desk, as the photographer focused the shot, the president asked the little Hoosier delegation who did more to help him win Indiana – Pence or Bobby Knight?

Knight, the Indiana University basketball coach with a legendary bad temper, had endorsed Trump in the final days of the GOP primary. Pence, the former Indiana governor, had helped Trump win over the religious right. Without missing a beat, Banks replied, “Definitely Bobby Knight.”

Looking back all these years later, he quips that there hasn’t been “a better political marriage than Bobby Knight and Donald Trump.” His relationship with the former vice president, on the other hand, is non-existent. He once predicted that “Pence will be president one day.” Now they don’t speak. Banks was just the second member of Congress to endorse Trump for president. Pence is the most prominent GOP critic of tariffs, and he calls it the “largest peacetime tax hike in U.S. history.”

“In many ways, he’s contradicting himself this time around,” Banks says of Pence, citing the much smaller and targeted tariffs the Trump-Pence administration placed on China. He adds, “I hope that he comes back around and recognizes it. There’s still time for him to do that.”

This is as unlikely as a reconciliation between the two. Banks has become more aggressive. He was harder charging during the Biden era, and his working-class memo, an overture to Trumpism, had come to the attention of the president’s eldest son, and de-facto talent scout, Donald Trump Jr. When Indiana Sen. Mike Braun announced that he would run for governor rather than a second term, the Trump family started looking for another ally.

“Do you want my endorsement?” Trump asked. “Sir, of course, I want your endorsement,” Banks recalled. “I said, I can’t lose if I have it.”

The support didn’t come in a vacuum. The empty Senate seat was attracting the wrong kind of attention from the Trump family’s perspective. Former Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels was reportedly exploring a bid. A fiscal hawk and an alum of the Bush administration, the Indiana elder statesman was a throwback to an older kind of Republicanism, decidedly skeptical of MAGA populism.

“If you are going to replace Mike Braun, replace him with someone who is going to stand up for Trump and the agenda,” Banks says of that shadow competition, “not with someone who will be the next Mitt Romney.”

In this way, the president was persuaded to give his endorsement, Daniels was convinced not to run, and Banks says, “a bloody and costly” primary fight was avoided. But even after Trump cleared the field for him, Banks kept going hard in the paint.

At the Republican National Convention, he warned the party faithful from the mainstage that “this was no time for wimpy Republicans” before taking a seat next to Trump and Vance in the presidential box suite. It was his 45th birthday. His speech, an advertisement for a new kind of Republican. The contrast is stark even in the Indiana Senate delegation.

Banks has spent his first three months in the Senate offering a full-throated defense of the tariffs and the trade war. His colleague, Indiana Sen. Todd Young, has pointed to economic consensus to argue not only that protectionism doesn’t work but that “Hoosier farmers, manufacturers, and rural communities” are often the first hurt by retaliatory tariffs. Donald Trump Jr. expected as much.

On the campaign trail, just outside Shelbyville in March of 2024, the eldest Trump scion kept his pitch short. “Jim Banks will not be Todd Young,” he said, pretending to walk off stage. “That’s all you needed, right?” The crowd roared in applause at the routine, offering an imprecise plebiscite of just where exactly the energy now resides in the modern GOP.

Banks isn’t as flashy as some of his new Senate colleagues, and the blowup with the fired federal employee seemed out of character for the usually measured and polite Midwesterner. Instead, he is more workmanlike in his approach to politics – Trump calls him “the strong-silent type.” But he is of a different breed compared to the Republican old guard. The Senate is also different.

“The guys who were Trump’s biggest obstacles have left,” he says of the long exodus of the president’s skeptics, “and have been replaced by strong, pro-Trump, pro-America First Republicans,” before adding that now “I’ve joined that club.”

And about that tariff bet: Banks remains bullish.

The senator called RealClearPolitics for a second interview shortly after the 100th day of the second season of Trump. Markets remained skittish, the Dow Jones Industrial Average in particular. According to the Wall Street Journal, that index had just experienced its worst start to a presidency since Richard Nixon’s second term in 1973. Was he nervous? “Not at all,” the senator said.

“The critics are looking at the wrong metrics,” he insisted. The right one is, instead, “the decline of China and the rise again of American manufacturing.” And Banks won’t blink.

“This is a huge moment for our country. We have got to get it right. We can’t back down. President Trump won’t. He’s always told me that in private – you never back down.” It doesn’t seem that the new senator from Indiana will either.

This article was originally published by RealClearPolitics and made available via RealClearWire.