The Louisiana Purchase and Pragmatic Presidential Power

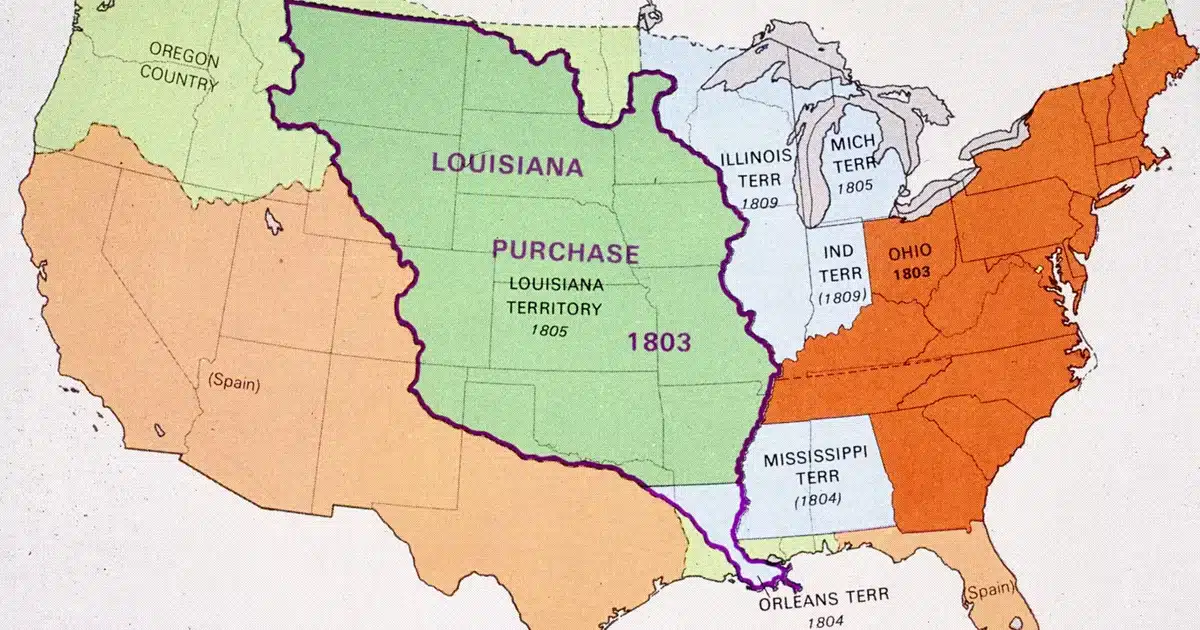

On April 30th, 1803, American diplomats in Paris reached an agreement with the French government to purchase the Louisiana Territory for approximately $16 million. It’s a massive but imprecisely defined tract of land between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, north of modern Texas.

According to the treaty’s terms, the United States would acquire approximately 828,000 square miles of territory, including the port of New Orleans. The territory included approximately 60,000 non-Native settlers (French, Spanish, African, and creole – half of whom were enslaved) and around 150,000 Native Americans.

The Louisiana Treaty was the result of prolonged negotiations between the U.S., France, and Spain over access to the Mississippi River. After the Spanish closed New Orleans to Americans in 1802, President Thomas Jefferson persuaded Congress to appropriate $2 million for the purchase of the port.

Napoleon Bonaparte had sought to revive the French Empire in the New World. His ambitions were frustrated by the successful resistance of formerly enslaved revolutionaries in Haiti, and in March 1803 he decided to sell all of Louisiana to the U.S. to finance his wars in Europe.

Word of the Louisiana Treaty reached Washington on July 3, 1803. Thrilled at the news, President Jefferson shared it with the editor of “The National Intelligencer,” a newspaper friendly to his administration. It published this brief note on the Fourth of July: “The Executive have received official information that a Treaty was signed on the 30th of April between the ministers of the U.S. and France, by which the U.S. has obtained full right to and sovereignty over New Orleans and the whole of Louisiana.” At noon, Jefferson appeared on the steps of the presidential mansion to greet a crowd gathered to celebrate American independence, and confirmed that the United States had struck a deal to acquire Louisiana.

Jefferson acknowledged the strategic importance of acquiring New Orleans and hoped that the U.S. might remain an agrarian republic, a goal he thought would be furthered by the addition of so much new, farmable territory. However, he harbored doubts about whether the Constitution authorized the president to acquire territory through such a transaction.

In coming to an agreement the American negotiators, Robert Livingston and James Monroe, had exceeded their mandate to negotiate the purchase of New Orleans for a smaller sum – which presented President Thomas Jefferson with a dilemma.

During the summer of 1803, Jefferson drafted a proposed constitutional amendment authorizing the purchase, which he shared with members of his cabinet, including Secretary of State James Madison, Attorney General Levi Lincoln, and Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin.

However, the treaty set a six-month deadline for ratification and implementation. Livingston, the American minister in Paris, reported that Napoleon was having misgivings. He feared that if the U.S. failed to meet the deadline, Napoleon would repudiate the agreement. Although he retained doubts about the treaty’s legality, Jefferson concluded that there would not be enough time to amend the Constitution.

Jefferson was aided by public opinion. The Louisiana Treaty was popular throughout the United States. Newspapers across the country welcomed the agreement as a diplomatic triumph. The Federalist opposition grumbled that East and West Florida weren’t included in the deal, but opposition to the treaty overall was limited.

On October 20th, the Senate ratified the treaty by a margin of 24 to 7. Eight days later the House of Representatives passed an act enabling Jefferson to take possession of and govern Louisiana, appropriating the funding to make it possible. The president signed the relevant legislation into law on October 31st, just within the six-month deadline required by the treaty.

Historians have often presented the Louisiana Treaty as a departure for Thomas Jefferson. After all, when he had served as George Washington’s secretary of state during the early 1790s, he had opposed Alexander Hamilton’s fiscal program on the grounds that the Constitution did not authorize such activities.

His response to the Louisiana Treaty, however, suggests that his “strict constructionist” views of the Constitution might have evolved. It seemed as though he embraced “broad construction,” the view that the Constitution allowed Congress and, especially, the president to take actions which were not specifically prohibited.

This has led Jefferson’s critics, then and now, to accuse him of hypocrisy. The man who sought to limit the power of his predecessors sought to exercise it when he became president.

Such a view, while tempting, is too simplistic. Jefferson had learned during his disastrous tenure as governor of Virginia during the War of Independence that executives sometimes need to take action in response to exigent circumstances. He did so early in his presidency when he ordered the U.S. Navy to North Africa to counter the threat posed by the Barbary states without calling Congress into session to seek a declaration of war.

However, Jefferson believed that while presidents might need to act quickly in a crisis, they should be subject to congressional oversight, as required by the Constitution. During the Barbary War he sought ex post facto congressional approval for his actions, which came in the form of funding.

In 1803 Jefferson reasoned that if the Senate ratified the Louisiana Treaty and the House of Representatives appropriated the necessary funds to make the purchase as required by the Constitution, then the treaty would be legally binding and his actions would be vindicated.

Pragmatism rather than hypocrisy might be the best way to describe Thomas Jefferson’s approach to presidential power.

This article was originally published by RealClearHistory and made available via RealClearWire.