Is It Time To End Mandated “Majority-Minority” Congressional Districts?

By

August 24, 2025

The Democrats’ hackneyed falsehood that Republican gerrymandering in Texas is racist and will end American democracy is not only hysterical – it’s hypocritical. While gerrymandering is ethically impaired, it has been part of U.S. politics for more than 200 years, and a mainstay of Democratic Party election strategy since the 1980s.

When redistricting is designed to favor one group over another, it is referred to as gerrymandering. Prior to the 1960s, court challenges to congressional redistricting plans were generally considered to be political questions outside judicial purview. In 1962, however, the Supreme Court held that federal courts could ensure compliance with the constitutional requirement of “one person, one vote” when Tennessee created districts with population variances as large as ten-to-one.

Courts also hear challenges to redistricting plans based on claims of racial gerrymandering under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, and the 15th Amendment, and until recently, also claims that a gerrymander was intended to benefit a particular candidate, ideology or party.

The Gerrymander

The gerrymander owes it heritage to Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry. In 1812, he signed off on a new state senate district so bizarrely shaped that his opponents said it looked like a salamander. A local newspaper cartoonist combined the two, and the “Gerry-mander” was born.

Except as an incidental consequence of its impact on voter enthusiasm or campaigns, a gerrymander does not change the total number or ratio of votes in any given state. Rather, it draws districts to allocate available votes in a manner that maximizes the number of districts in which the party controlling the process obtains a majority.

States usually redistrict every 10 years, following the decennial census. That census is used to reapportion the 435 congressional seats to, and track population shifts within, each state. Under Article I of the Constitution, state legislatures are responsible for redistricting. Republicans currently control both houses and the governor’s office in 23 states, and Democrats in 15 states. Eighteen states also use commissions in the redistricting process, including eight independent commissions that supplant the legislature’s traditional role. In 2015, the Supreme Court approved this practice.

According to the Brennan Center, a progressive public policy institute, congressional and legislative redistricting maps based on the 2020 census were challenged in 90 lawsuits involving 28 states, including 61 cases contending that GOP-crafted maps were either racially or politically discriminatory (or both). Forty-nine lawsuits asserted racial gerrymandering, and 42 asserted partisan gerrymandering. Courts have ordered changes in 13 states, with 38 cases still pending.

Over the last two cycles, both major political parties have gerrymandered numerous states, including using the VRA to create “majority-minority” districts in which Democrat-leaning blacks or Hispanics constitute a majority of voters. Former Obama Attorney General Eric Holder has earned gushing praise from the media as the architect of many of these gerrymanders through his National Democratic Redistricting Committee.

The most successful gerrymander in history may have been the combination of the 2020 census and the Obama and Biden administrations’ admission of tens of millions of illegal aliens. The U.S. Census Bureau acknowledges that in 2020 it overcounted in eight states and undercounted in six, costing Republicans an estimated six seats. According to White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller, the GOP lost at least 20 additional seats by including illegal aliens in reapportionment. On his first day in office, President Trump ordered the census to exclude illegal aliens from congressional apportionment. Last week, he instructed the Commerce Department to begin work on a new census complying with that order.

In an all-out redistricting war, Democrats likely would lose because they have largely maximized their available benefits, with the proportion of Democrat seats vastly exceeding the Democratic percentage of the vote in many states. By contrast, Republicans have fertile opportunities – not just in Texas, but also in Ohio, Indiana, Missouri, Florida, and potentially other states. In total, Republicans could gain as many as 15 seats in the midterm elections.

Until now, Democrats have been constrained because California and New York have delegated redistricting to independent commissions. Govs. Gavin Newsom and Kathy Hochul are attempting to end-run these restrictions. It is uncertain whether such efforts to bypass the commissions would survive court challenges, and a Politico-Citrin poll last week shows that two-thirds of Californians would vote against modifying their independent commission system to elect more Democrats.

Texas

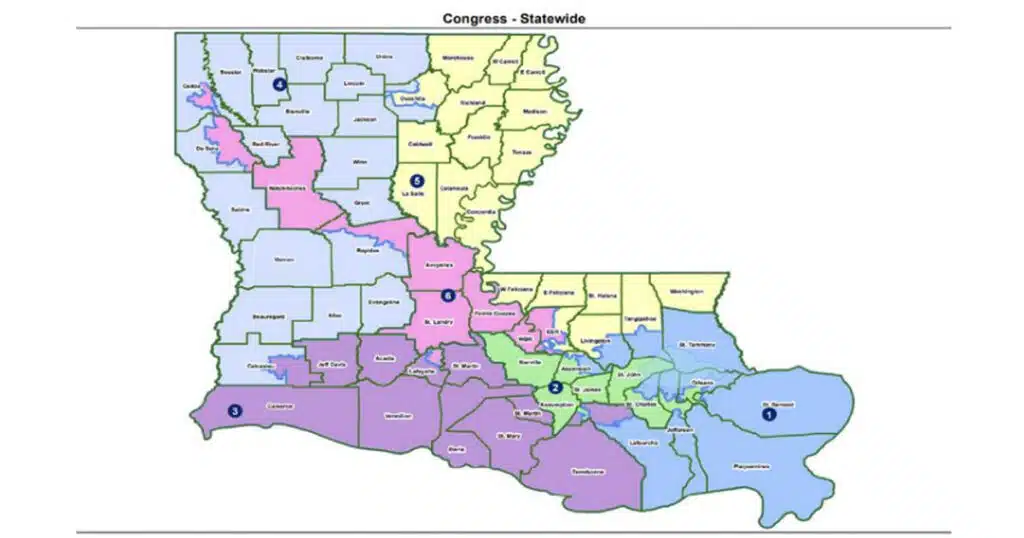

In July, Texas Republicans announced a redistricting plan that may swing the state’s delegation from 25 Republicans and 13 Democrats, to as many as 30 Republicans and just 8 Democrats, though a Texas Tribune analysis concluded that Republicans might gain as few as three seats.

To Democrats, the GOP’s Texas gambit is uniquely evil because it is redistricting after five years, rather than waiting for the end of the decade. There is no federal or state prohibition on more frequent redistricting, and Texas’ process is not unprecedented – not even in Texas.

Holder called the Republican redistricting in Texas “an existential crisis” and claims that it is an “egregious” effort to disenfranchise blacks and Hispanics. Other critics falsely contend that the purpose of the Texas plan is to reduce the number of majority-minority districts.

These attacks are based on two shaky premises – that blacks and Hispanics don’t vote for Republicans, and that people only vote for candidates of their race. According to CNN, in the last presidential election, 55% of Latinos and 12% of blacks in Texas voted for Trump. The list of black and Hispanic officials elected by majority white electorates is long, and includes, in Texas alone, Ted Cruz, Colin Allred, and Julian Castro, among others.

In fact, the Republican plan creates an additional majority Hispanic district, and two majority black districts, where previously there were none.

Though Texas Republicans are redistricting to increase Republican representation, their plan also remedies errors in the 2020 census, adjusts for migration to Texas that has increased the state’s population by more than 8% since 2020, and resolves claims made in July by the Justice Department that four congressional districts created in the state’s last redistricting plan are unconstitutional “coalition districts.” A coalition district is a majority-minority district created by combining two racial and language minorities.

To stop the Texas legislature from acting, a majority of its Democrat members left the state, temporarily depriving the Texas House of a quorum. Ironically, the state to which most of them absconded, Illinois, is one of the worst abusers of the gerrymander. The congressional map drawn by Illinois Democrats after the 2020 census transformed its congressional delegation from 13 Democrats and 5 Republicans to 14 Democrats and just 3 Republicans – in a state where Donald Trump won 44% of the 2024 vote. The respected Gerrymandering Project at Princeton University gave Illinois an “F” for its partisan gerrymander.

Evolving Law

According to Article I, “[t]he Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations….”

The Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment provides that “[n]o State shall make or enforce any law which shall … deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, and the 15th Amendment guarantees that “[t]he right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The VRA authorizes the federal government and private citizens to challenge voting qualifications or practices that deny or abridge the right to vote based on race, color, or language. A 1982 amendment made clear that a discriminatory effect violates the VRA, regardless of purpose, but also clarifies there is no guarantee of a proportional outcome.

After years of uncertainty, the Supreme Court last year held in Rucho v. Common Cause that while partisan gerrymandering may be “incompatible with democratic principles,” it is a “political question” that is beyond the authority of federal courts to decide. As a result, states are now free to reduce Democrat or Republican representation in Congress, so long as they comply with basic rules of “one person, one vote,” and the districts are geographically compact, contiguous, and respect political boundaries, such as county lines.

For districting that allegedly disempowers minorities, the Supreme Court set out a three-part framework in Thornburg v. Gingles (1986). The minority group must be sufficiently numerous and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a reasonably configured district. It must be politically cohesive. And, the white majority must be able defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.

Paradoxically, a recurring remedy for these claims is to use race to create majority-minority districts. As recently as 2023, Chief Justice John Roberts (who in 2007 believed that the “way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race”) and Justice Brett Kavanaugh joined the liberal justices in Allen v. Milligan to find that Alabama likely violated the VRA by failing to create a sufficient number of majority black districts.

Many conservative scholars argue that the 14th and 15th Amendments are intended to bar government’s use of race. Under this view, though courts may enjoin redistricting plans for limiting the rights of racial minorities, the Constitution prohibits the creation of districts based on the race of voters.

The false factual conceit of majority-minority districts is that people vote as monoliths based on their race and the race of candidates. Today, when a majority of black, Latino, and Asian Americans live in diverse suburbs, millions vote for candidates of other races, and candidates of all races are prominent Republicans and Democrats, the rationale for majority-minority districts has never been weaker.

Last week, the Supreme Court announced that it will hear Louisiana v. Callais to determine the constitutionality of a second majority-minority district. Given its recent decisions, the high court may bow to reality and restore the intent of 14th and 15th Amendments, impacting the constitutionality of all purposely created majority-minority districts. If it does, progressives undoubtedly will shriek about racism, the end of democracy, and the illegitimacy of the Supreme Court itself.

When Democrats engage in gerrymandering, arrogating 30 to 50 seats for which the voters would prefer Republican representatives, they, progressive academics, and the media praise the outcome as a guarantee of liberty. When Republicans defend against this encroachment, or use the Democrat playbook, progressives reflexively insist that Republicans are racists, intent on ending democracy.

It is time to end court-ordered majority-minority districts, exclude illegal aliens from congressional apportionment, and get an accurate census. Then, if Democrats want to end gerrymandering, let’s have that discussion. Until then, a little ol’ Texas gerrymander is a good and lawful step forward.

This article was originally published by RealClearPolitics and made available via RealClearWire.