We Should Not Be Digital Slaves

How Meta’s Monopoly Enables Massive Data Overreach

Greed is a powerful motivator—not just for individuals, but for corporations as well. And Meta’s corporate greed has transformed one of our most valuable assets, our personal data, into a resource that’s harvested, monetized, and exploited without meaningful consent or control.

Meta’s monopoly in personal social networking services has created a surveillance apparatus so pervasive that it tracks your every move—not just when you’re doom-scrolling through Facebook or Instagram, but even when you’re using incognito mode or filling out government forms online.

The FTC v. Meta antitrust trial, which wrapped up on May 27, revealed just how far the company went: In 2013, Meta purchased Onavo, originally a secure virtual private networking service, and then repurposed it to secretly surveil users across the Internet.

Meta used Onavo to track users’ internet activity and collect data on traffic to competitor apps like Snapchat. This gave Meta a blueprint to suffocate competitors by hijacking signature features to use for their own services. One example is Instagram Stories—a feature eerily similar to SnapChat Stories.

Onavo is just one of many tools Meta has used to fatten its database and harm competitors. The company has built a vast surveillance network that follows you across the Internet through tools like Meta Pixel, a piece of code Meta provides to websites to track their visitors. One investigation found Meta Pixel is embedded in 30% of the top 100,000 websites and has at least 2.2 million total installations.

Through this pervasive tracking network, Meta quietly collects your browsing history, your financial information, and even your sensitive health data.

For example, Meta was able to collect data from students who filled out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid. More disturbing, a 2022 investigation revealed that Meta was actively collecting sensitive patient data from one-third of the top 100 U.S. hospitals—data that included medical conditions and prescriptions.

2025 investigations have shown that Meta tracks Android users’ web browsing activity even when they’re using incognito mode or VPNs, two tools that are supposed to provide stronger privacy protections.

You don’t even need a Facebook account to be in its crosshairs. The company collects data from non-users through their browsing history and through contacts shared by friends and family who use Meta’s services. Even if you’ve opted out of social media, you may be profiled by Meta to serve you ads that can convert you into another monetized user.

Now, Meta is extending this surveillance to its AI products.

According to one study, the company’s AI chatbot now collects more user data than any other major platform AI chatbot, even when compared to DeepSeek, a Chinese Communist Party-based AI system. Let that sink in: An American tech company’s system is more invasive of user data than is a system developed under the CCP’s influence.

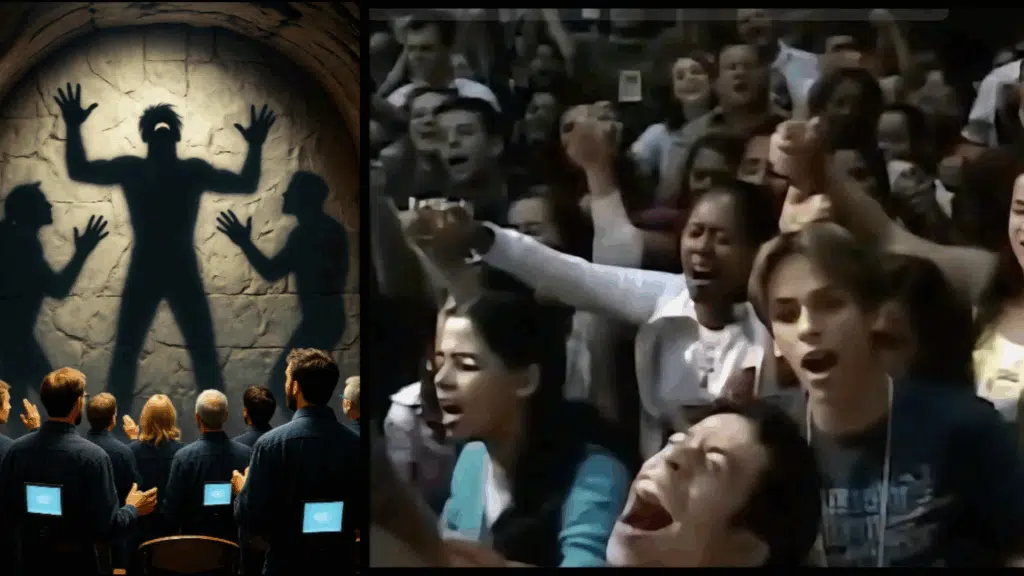

This Big Brother type of surveillance is the direct result of Meta’s monopoly position in personal social networking services. Without meaningful competition, there is no reason for Meta to give consumers the option to opt-out of its overly greedy data machine. Consumers could even forgo social media entirely and still find their names in Meta’s database.

If we had genuine competition in the social media space, consumers could choose platforms that better align with their privacy preferences. As the FTC argued, this would allow users to select services based on the quality of data privacy protection options. Robust competition would foster a market where privacy is a feature, not a sacrifice.

Some may claim the privacy battle is already lost. But resignation is not an answer. Digital privacy isn’t just about secrecy—it’s about autonomy, ownership, and dignity. Your data is your property. Every byte Meta collects without your consent is another intrusion into your personal life and another blow to self-governance.

The fight for digital privacy matters not just for us, but for our children. Do we want to leave them a world where being constantly monitored is accepted as the price of participating in society? Or do we want to restore the principle that people should have control over their own information?

Beyond personal harm, Meta’s data overreach undermines trust in American technology companies globally. If we want global adoption of U.S. technology, we must build systems that respect user privacy and build user trust. This requires reining in monopolies that have grown so powerful they can ignore consumer preferences for privacy.

Two decades ago, this level of surveillance would have been unimaginable. Today, it is reality—but not destiny. The FTC v. Meta case is about more than competition law: It’s a chance to reclaim a future where privacy is protected, where trust is earned, and where technology serves the human person—not exploits them.