Exodus: Affordability Crisis Sends Americans Packing From Big Cities

This is the first in a two-part series of the Great Dispersion of Americans across the country.

For much of the past century, in both the United States and elsewhere, the inexorable trend has been for people to move from rural areas and towns to ever larger cities, particularly those with vibrant downtown cores such as New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Seattle, and dozens of other iconic American cities. Most visions of the future still view urban cores as the uncontested centers of production, consumption, and culture, with rural areas, small cities, and suburbs relegated to the backwaters of modernity.

A RealClearInvestigations analysis has found that we may be on the cusp of a new era. Urban cores have started to shrink, losing first to the suburbs, then to ever further exurbs, and now to small towns and even rural areas. For the first time since the 19th century, America’s growth pattern favors smaller metros – Fargo, North Dakota, as opposed to Portland, Oregon – many of which once seemed out of favor.

This transformation can be hard to detect because demographers often discuss metropolitan regions, which put city centers at their cores. But this method of classification masks the trend that much of the growth is at the edges of these areas. In virtually all the fastest-growing metros, it has been the further-out exurbs, themselves until recently rural areas, that have experienced most of the expansion. While Raleigh, North Carolina – a sleepy state capital for much of its history – continues to draw migrants from across the country, the most explosive growth is not occurring in the city center but the surrounding “countrypolitan” towns of Apex, Fuquay-Varina, and Zebulon that offer land and a relaxed rural environment along with access to modern amenities.

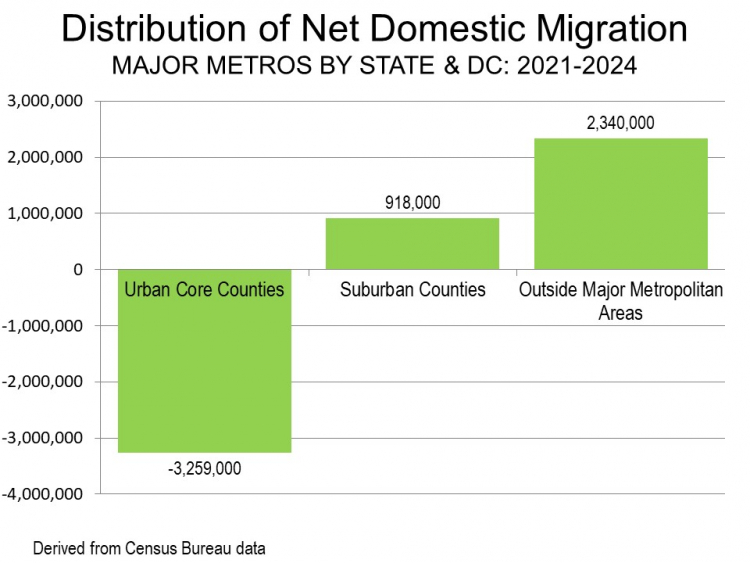

Between 2010 and 2020, the suburbs and exurbs of the major metropolitan areas gained 2 million net domestic migrants, while the urban core counties lost 2.7 million. The pandemic, which normalized remote work and encouraged people to keep their distance, turbocharged this movement to smaller, less crowded, less expensive housing markets. Through the first four years of this decade, the urban core counties of the major metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000 population) lost 3,259,000 net domestic migrants, three times the rate of loss in the last decade. In contrast, 2.3 million net domestic migrants moved outside the major metros.

Net Domestic Migration

RCI

This is a shift the media has underplayed or pinned almost entirely on the pandemic, leaving the impression that small towns and rural areas have little to offer other than a safe haven from illness and crime. In a pre-pandemic 2018 article asking “Can rural America be saved?” the New York Times reported that small cities and towns, particularly in the middle of the country, were “getting old” and facing “relentless economic decline.”

The data suggest the opposite: that Americans are heading back to the land. The steep costs of urban housing and an Amazon economy that allows anybody, anywhere to get almost anything, is rekindling our deep-seated desire for privacy, space, and home ownership.

The New Demographics

The first phase of geographic reinvention began to take shape by 2000, as workers followed both U.S.- and foreign-based companies, which were increasingly expanding into lower-cost states in the Sun Belt and Midwest. Since then, the two most urbanized big states, California and New York, have each lost more than 4 million net domestic migrants. Two other trends – a drop in immigration and fertility rates, especially among people living in big cities – are making it hard for these states to restock their urban populations.

Although the many efforts to revive downtowns have helped lure newcomers, at least temporarily, most people moved to the periphery; suburbs account for about 90% of all U.S. metropolitan growth between 2010 and 2020, with the greatest increase in the farther-flung exurbs. The most notable expansion is not occurring on the fringes of behemoths like New York City and Chicago but in and around smaller metro areas. Between 2015 and 2023, areas whose growth more than doubled the national population increase included the Texas cities of Killeen and Sherman; Savannah and Jefferson in Georgia; Spartanburg, South Carolina; Daphne, Alabama; Naples, Florida; Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Hagerstown, Maryland; and Clarksville, Tennessee. In these last three – Sioux Falls, Hagerstown, and Clarksville – the new settlements actually spill over into neighboring (and even more rural) states.

This process may only be in its early phase, driven by the rush of millennials as well as immigrants. In the past, notes urban analyst and midwestern native Aaron Renn, much of the urban growth in the Midwest has come from migration from smaller towns in their region instead of from the coasts. The demographic vitality of places like Indianapolis and Columbus, for example, has been primarily from surrounding metro areas and rural regions.

This is now changing as both foreign and domestic pilgrims are increasingly attracted to these smaller towns. We are witnessing a world turning upside down from the realities of the last century. Even the greatest exemplar of 20th-century growth – Los Angeles County – is now shrinking, and according to state estimates, will lose an additional 1 million people by 2070. Meanwhile, many smaller areas, notably in the South and Midwest, from which many Angelinos (and their parents) originally came, are enjoying something of a demographic recovery.

Housing Costs Driving the Big Metro Exodus

This shift reflects, more than anything, the rising cost of housing, which accounts for about 88% of the difference in the cost of living between expensive big city areas and the national average. As RCI previously reported, much of this extra cost results from the strict peripheral land regulations that have driven prices up in many metropolitan areas. High housing prices initially helped drive migrants from California to places like Oregon, Washington, and Colorado. But now those states have begun to adopt the same regulatory schemes with the same result: lower job growth, sluggish housing-construction rates, a deteriorating business climate, and surging domestic outmigration. This is a principal factor in the declining homeownership rates and domestic outmigration afflicting big cities.

While the shift to smaller metros has many sources – including the migration of older Americans looking for less expensive places to live and the return to the South by many African Americans – perhaps more critical has been the movement of young families. The key here is home ownership, the traditional way to build wealth and enter the middle class. It has been in decline, not in terms of desire but the chance of achieving it, for half a century.

Since the pandemic, U.S. house prices have risen strongly, seriously eroding affordability. In a market defined as affordable, the “median multiple” (which divides the median price of a house by the median income) registers at 3 or less. Right now, the average for the entire United States is over 4, but much higher in some markets – 10 or more in San Jose, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego, and 7 or more in San Diego, Miami, New York, and Seattle.

Not surprisingly, housing is usually more affordable in smaller markets and rural areas. American Community Survey data indicate that there are about 120 metropolitan areas in the United States with median multiples of 3.0 or less. In 2024, many of the more affordable metro areas could be found in former industrial centers such as Pittsburgh (3.2), Cleveland (3.3), St. Louis (3.5), and Rochester (3.6). The best bargains for first-time homebuyers, according to Zillow, are in smaller markets, where median multiples were 3.0 or below, such as in Wausau, Wisconsin; Cumberland, Maryland; Terre Haute, Indiana; and Bloomington, Illinois.

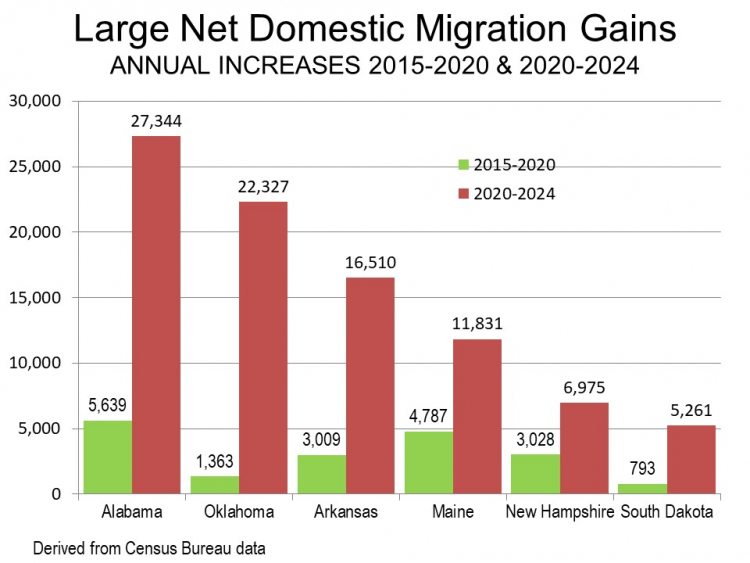

This development has helped spur significant gains in net domestic migration in states like Alabama, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Maine, New Hampshire, and South Dakota. All of these states have a lower cost of living than the national average, except for New Hampshire, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Migration Gains

RCI

Broad Rise of Smaller Places

The shift from the most urbanized regions and states has also been fueled by job growth. It has shifted decisively in recent years to less urban and lower-density states such as Idaho, Utah, Texas, the Carolinas, and Montana. In contrast, big urban states like New York, California, Illinois, and Massachusetts sit toward the bottom. This pattern also applies to smaller metros like Fayetteville, Arkansas; Greenville, South Carolina; Grand Forks, North Dakota; and Ogden, Utah, where job growth soared most dramatically.

At the same time, some formerly booming metro areas like Seattle, Denver, and Portland have experienced reduced net domestic migration as prices have risen and economic opportunities have shifted. Domestic migrants are increasingly turning to smaller metropolitan areas. In each of these once “hot” metros, domestic migration has switched to smaller markets, such as Spokane, Centralia, and Shelton in Washington, and Greeley and Grand Junction in Colorado, according to our analysis of Census Bureau data.

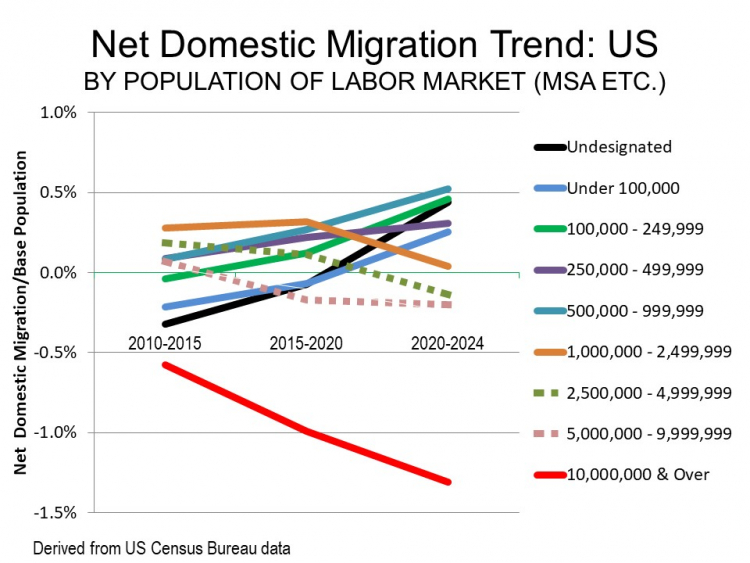

This represents a reversal of the strong century-long trend, with larger metropolitan areas gaining the most net domestic migration. RCI’s analysis of Census Bureau data finds a stark turnaround from the period 2010-2015, when all categories of communities with fewer than 250,000 residents had more people leave than arrive.

The new data through 2024 reflects a profound reversal of this earlier trend, a shift from patterns that have existed for at least a century. Each of the population categories of 1,000,000 or more lost net domestic migration after 2015, while all of the smaller population categories gained net domestic migration.

Migration Trend US

RCI

Millennial Move to Smaller Places

The challenge of paying rent, much less buying a house, is transforming the decisions people make about where to live, particularly for those seeking to establish families or achieve middle-class lifestyles. “While I had a great job and a great apartment [in New York], I didn’t see how that would translate in the future to having a house or having work-life balance,” explained Katie MacLachlan, co-owner of the bar Walden in East Nashville. “I didn’t feel like New York City had that to offer unless you’re a billionaire.”

This marks a dramatic reversal from the faith in the mainstream media that millennials would inevitably flock to the big coastal cities and avoid smaller towns as backward, boring, and prejudiced. But repeating a meme does not make it true. Bigger core cities, such as New York, have actually lost both people, including young people between 25 and 39, since 2020. The much-ballyhooed era of elite coastal big city domination and small metro decline, so widely proclaimed in the national media, may well be past its sell-by date. In fact, after attracting the larger share of migrants between ages 25 and 44 for much of the past half-century, the big metro share has fallen since 2010, while smaller metros, and particularly areas with under 250,000 people, have surged in their appeal.

These migrants are finding that their conditions improved by moving. As Brookings Institution scholar Mark Muro has noted, salaries across a 19-state American Heartland region, adjusted for the cost of living, are above the national average. Another study found that of the 10 areas with the highest cost-adjusted incomes, eight are in the heartland. In contrast, those with the lowest adjusted incomes were entirely on the ocean coasts.

Overall, many of the highest-salary metros look far less alluring for maturing adults and families. Among the 185 U.S. metro areas with at least 250,000 people, cost-of-living-adjusted salaries are highest in Brownsville-Harlingen, Texas, Fort Smith, Arkansas, and the Huntington-Ashland area, which spans the tri-state area in West Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio. All 10 of the highest average salary metros are small and mid-size markets – none has more than 1 million people. Most are in the center of the country, and the only two in an expensive state – Visalia-Porterville and Modesto in California’s Central Valley, far from the state’s pricey coast.

This shift also corresponds to the maturation of millennials. Despite media accounts that young people do not want to start families or own homes, most surveys show that the vast majority of Americans in their 30s want to replicate these foundations of middle-class life. Some 1 million millennials become mothers every year. Many seem attracted to smaller metros, where you can live near an old Main Street and not too far from farms that offer fresh produce. This lifestyle has been described as “urbalism,” which mixes proximity to a metro center and airport while still living in what remains a largely rural setting.

Nationally, the age of the average homeowner is rising, up from early 30s in 1980 to 56 today. The places where people under 35 represent the largest share of new homeowners, however, are overwhelmingly in the Midwest, as well as in Provo, Utah, Colorado Springs, and Bakersfield, California. “The data shows that they leave [big metros],” said Nadia Evangelou, author of a recent National Association of Realtors study. “They cannot afford it, so they probably leave for that reason.” One study found that while 20% of people under 35 in places like Sioux Falls, South Dakota, an emerging tech center, own their own home, only 3.5% in San Jose can make the same claim.

Immigrants Join the Parade

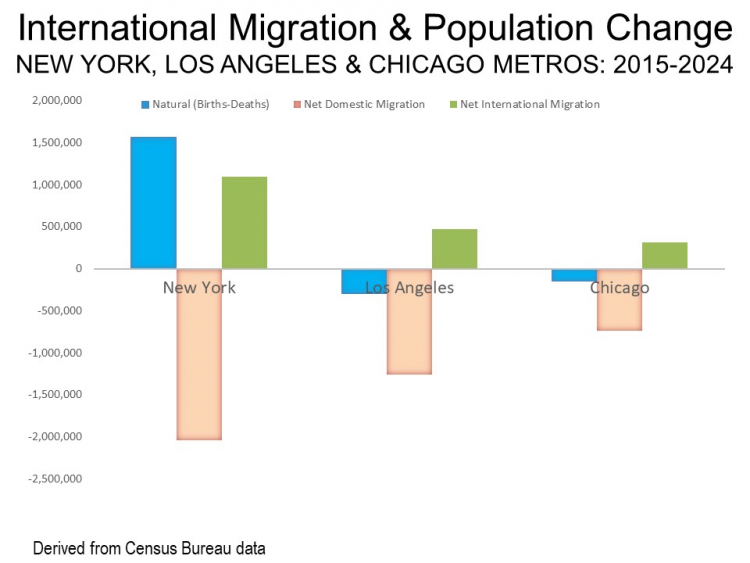

As domestic migrants increasingly left the big metros early last decade, immigrants from abroad made up for the loss. In the New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago metros, the net international migration continued, but was outpaced by outmigration of current residents since 2020 But now, for the first time since the pioneer age, medium sized metros like Columbus, Indianapolis, and Des Moines, are now attracting a higher percentage of foreign migrants than traditional centers like Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area, or New York.

Birth Rates

RCI

In the process, for example, Omaha, Nebraska, has just hit the 1 million population mark. Omaha has become much more ethnically diverse, experiencing rapid foreign-born growth of 28% from 2010 to 2019, more than double the 13% national rate, according to Census Bureau data. Although only 7% of Nebraskans are foreign-born, there are wide swaths in the Omaha area that reach over 20% foreign-born, with large numbers speaking another language at home. It may not be the turn of the century Lower East Side redux, but it signifies an ethnic change that few would have anticipated.

America’s New Nurseries

Rather than havens for the old, small metros and rural areas are now America’s prime nurseries. States in the Midwest and South, including North Dakota, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Arkansas, and South Dakota, account for seven of the 10 areas aging the least rapidly from 2000 to 2023. North Dakota, once seen as hopelessly geriatric, has aged the least of all states since 2000.

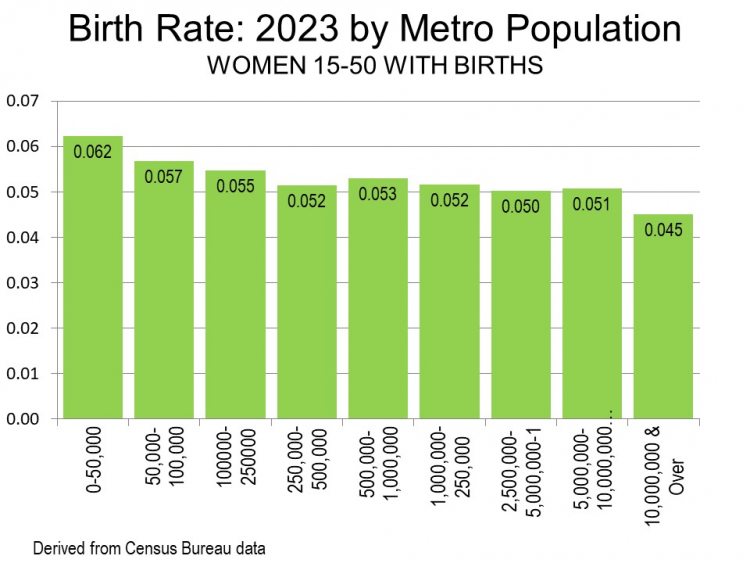

Much of this is connected to fertility. Overall, lower-density locales – with affordable homes, safe streets, and strong community cultures – are more conducive to families than denser urban areas. Eight of the 10 youngest big metros are located notably in the exurbs and smaller metros in the South, Midwest, and Mountain census regions. Rather than places doomed to become smaller and geriatric, these less dense places are becoming the nurseries of the nation.

Four of the six states with the highest birth rates were in North Dakota, South Dakota, Kansas, and Nebraska. At the same time, 14 of the 15 states with the lowest fertility rates were located in the Northeast and the West Coast.

In terms of metros, those with lower-than-average birth rates included Los Angeles, New York, Portland, Seattle, Boston, Milwaukee, Chicago, Denver, San Francisco, Orlando, and Providence. In contrast, the highest birth rates were in markets with fewer than 250,000 residents – and they peaked in markets of 50,000 to 100,000 residents. Leading the pack were smaller markets such as Wheeling, West Virginia; Cheyenne, Wyoming; Clear Lake, California; Jacksonville, North Carolina; Decatur, Illinois; and Hobbs, New Mexico.

Population Change

RCI

The Future Is Dispersed

This shift in families says much about the future. Societies with low birthrates – as we now see in much of Europe, East Asia, and virtually everywhere but Sub-Saharan Africa – inevitably suffer a kind of cultural stagnation. They tend to have less demand not only for housing and other products but also for ideas. Young people, notes economist Gary Becker, are critical to an innovative economy, and in the U.S., more of them are likely to come from the interior.

Rather than see this movement as a negation of the American Dream, it is actually an enhancement, an echo of the great migrations that have expanded opportunities across this vast continent. The new dispersion does not mean the decline of the nation or the death of big cities. But the overall shift to smaller and revival of metros underscores the ever-adaptable nature of the “pursuit of happiness” that drives the relentless search by Americans for a better life.

This article was originally published by RealClearInvestigations and made available via RealClearWire.