From Septuagint to Vulgate—And Beyond: Jerome’s Defense of Scripture

On Tuesday, the Feast of St Jerome, I used the occasion to highlight what I see as one of the great hinges of Christian history: how we translate the Bible, and how mistranslation–especially in the 20th century under the Scofield influence–can shape geopolitics, faith, and even souls.

My thesis was consistent with my ongoing work of bringing into necessary question the geopolitics in the Middle East first, and second (and connected very intimately), bringing into question the inescapable differences between Classic, Traditional Catholicism and what those popes and ecumenical councils taught and the Catholicism that has developed in the last century and what those popes and councils are saying, with the Second Vatican Council being a useful tool to engage conversation, while of course not covering the whole story. It concerns the stirrings I have in relation to pre-latter, latter, and end times prophecies.

It is why most if not all of those Catholic websites and YouTube influencers are not trustworthy. Most Catholics don’t know that, so I wouldn’t expect non-Catholics to know it either. As I’ve explored in the political realm as well, the reality of controlled opposition is real in the Catholic media world, and is leading countless Catholics down the wrong path. We have point blank seen just this week that these influencers are paid off by a certain State to push propaganda, one post at a time. It would be wise to guess that this applies to both the political and the religious realms.

So Douay-Rheims vs Scofield, in a nutshell, was the binary I was setting up in the article. If I had to offer another purpose, it is to further my ongoing recruitment of Modern Catholics to practice the Traditional way, most importantly through the liturgy.

In fact that latter may be the deepest motive of anything I do, if I really sit there and think about it, given my love for family and old friends.

In any case, and back to the moment at hand, Hayride writer Walt Garlington responded to my article with one of his own. It was well-received.

A Glance at Jerome’s Thoughts

Today I want to address those items that would have made my Tuesday article entirely too unwieldy, given my thesis on Scofield. I think that is only fair to St Jerome, named one of the four great Doctors of the West, whose translation of the Bible gives us “Do penance” instead of “Repent,” and “God’s justice” instead of “God’s righteousness,” two perhaps seemingly small things that have utterly changed my approach to giving God my all. Given St Jerome’s linguistic brilliance, an anomaly at the time, it should be plain enough for anyone to guess that he was well aware, and in intimate contact with, the Septuagint. We need to listen to Jerome himself, however, particularly because the East-West split wouldn’t occur until much later in history. His prologues and letters reveal how seriously he took translation, canon, and doctrinal fidelity. It took him more than just a few months or even years, to complete his prodigious undertaking:

It was wholly made at Bethlehem, and was begun about a.d. 391, and finished about a.d. 404. The approximate dates of the several books are given before each Preface in the following pages.

Respect.

Walt’s useful primer on a crucial component of Biblical history reminds readers of a central tension in Christian textual history: different manuscript traditions and translations have shaped doctrine and devotion in decisive ways. That overview is valuable. If it is putting St Jerome at odds with the Septuagint, however, it needs a careful addition to make clearer Jerome’s actual method and motive.

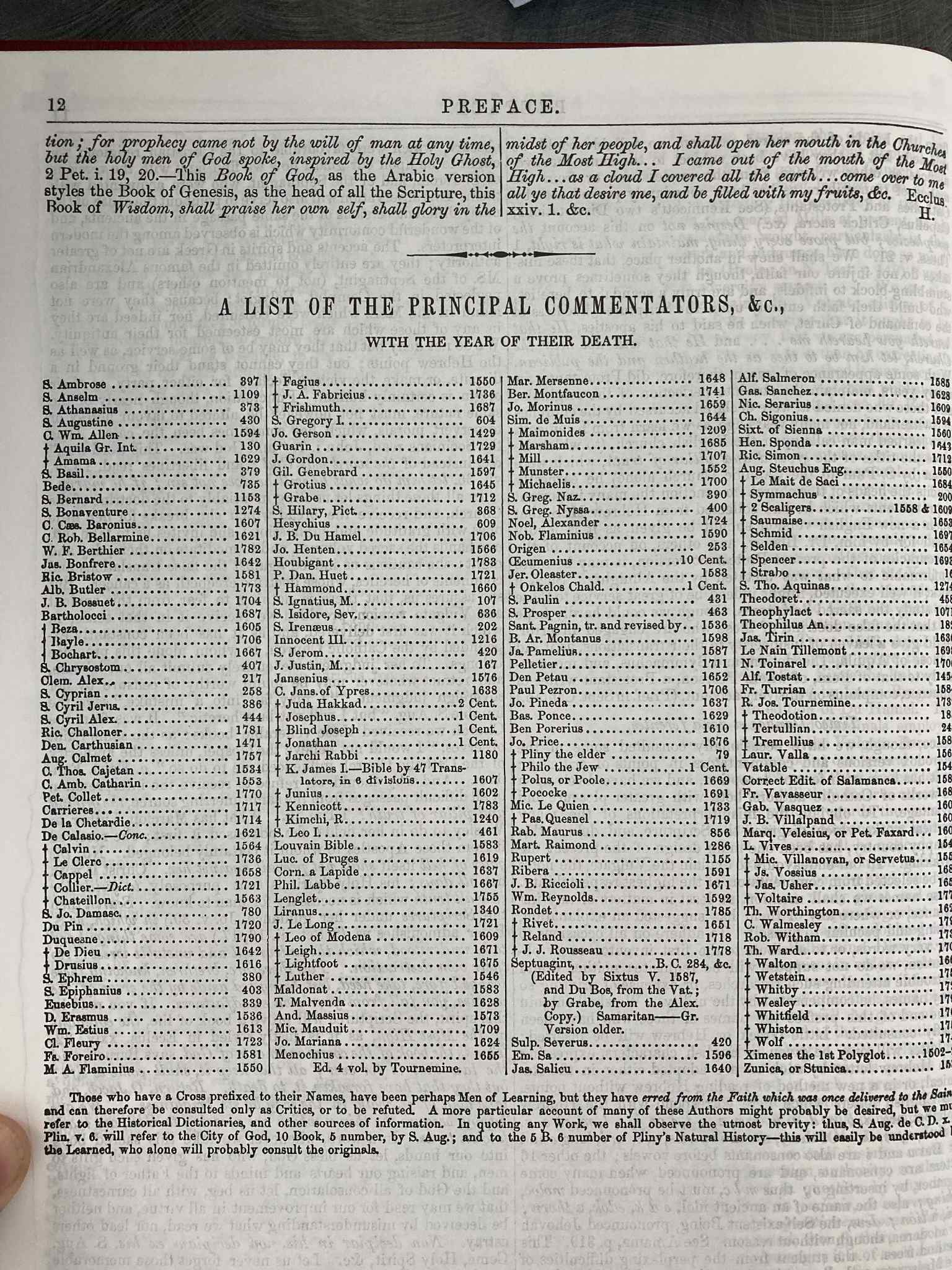

Not to mention the fact that the Catholic Church indeed honors the Septuagint in and of itself, even beyond Jerome’s contribution. At article’s end, I will include screenshots of the Preface to my copy of the Haydock Version of the Douay-Rheims, which says as much.

It also makes clear that the process of accurate Bible translation encounters numerous–numerous–obstacles and issues that any translator must be aware of. This can even get into those who transcribe it in the future or those printing presses in charge of printing new Bibles. This can nullify any initial translation, no matter how inspired it might be.

This opens the admission–made by the Preface of the Douay-Rheims itself pictured in screenshots below–that no translation is perfect. One of Walt’s main points was to show the separation between the Septuagint and the Vulgate and to use Catholic News Agency (Modern Catholic) to show that even D-R admirers admit it isn’t perfect. For numerous reasons detailed in the Preface screenshots, again, this is not a point any supporter of the Douay-Rheims rejects. Not even Jerome rejected–because he and they all know what time and fallen man can do to the translation of a text.

Jerome was well aware of the honor the Septuagint (termed “Seventy translators below and in Walt’s piece) had earned, and often seems frustrated with his detractors who seemed to not understand what he was working to accomplish. This site is dedicated to Jerome’s Prologues to the Old Testament translations (there’s that word again!) by Kevin P Edgecomb:

I am forced, through each of the books of Divine Scripture, to respond to the slander of adversaries who accuse my translation of rebuking the Seventy translators, not as though among the Greeks Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion had also translated either word for word, or meaning for meaning, or by mixing both together, also a kind of translation of equal proportion, and also Origen had divided all the scrolls of the Old Instrument with obeli and asterisks which, either added by him or taken from Theodotion, he added to the ancient translation, proving what was added to have been lacking. Therefore my detractors should learn to accept in full what they have accepted in part, or to erase my translation along with their asterisks….

For which reason, let my dogs therefore hear me to have labored at this scroll, not as rebuking the ancient translation, but rather so those things in it which are either obscure or missing or certainly corrupted by the error of scribes may be made more clear by our translation, who have both learned Hebrew speech in part, and also in Latin, almost from our cradle we were worn out (?) among grammarians and rhetors and philosophers….. Each edition, the Seventy according to the Greeks and mine according to the Hebrews, was translated into Latin by my labor. May each one choose what he will, and prove himself studious rather than malevolent.

It is difficult reading at times, sure, but I invite you to peruse that site. I do wonder what a man would think he benefits in such a toil of 13 years unless he understood it as both necessary for the Latins and a gift of self he was giving back to God to spread his Gospel to all nations.

OTHER VOICES

How Septuagint Shed Light On Early Hebrew Text

Why Jerome Rejected Parts Of The Septuagint

This site, while an English rendition in and of itself, will provide a more robust picture as to the difficulties St Jerome was undertaking. Here is just one of numerous examples:

Psalms.

Dedicated to Sophronius about the year 392. Jerome had, while at Rome, made a translation of the Psalms from the LXX. [moniker of sorts for the Septuagint, as Walt mentions], which he had afterwards corrected by collation with the Hebrew text see the Preface addressed to Paula and Eustochium, infra). His friend Sophronius, in quoting the Psalms to the Jews, was constantly met with the reply, “It does not so stand in the Hebrew.” He, therefore, urged Jerome to translate them direct from the original. Jerome, in presenting the translation to his friend, records the intention which he had expressed of translating the new Latin version into Greek. This we know was done by Sophronius, not only for the Psalms, but also for the rest of the Vulgate, and was valued by the Greeks (Apol. ii. 24, vol. iii. of this series, p. 515).

Here is one more resource from Taylor Marshall on St Jerome and the Deuterocanonical Books. Marshall is a popular Catholic influencer who should not be fully trusted because he is clearly not allowed to discuss deeper issues at play in the spiritual realm, but when it comes to certain topics, he is a good enough place to start.

By the way, has anyone ever actually done any work on translating an ancient language? I took a class that showed the complexities of it. It’s mind-boggling, the thought and decisions that must go into it. I hated the mere single paragraphs we were charged with unpacking.

Thirteen years of it?

More of Jerome’s Mind

St Jerome himself warned about all of these challenges and encouraged the Church over the centuries to be in constant touch with what words actually reach the faithful’s eyes. Indeed, even later saints have suggested amendments to the Douay-Rheims. You will see it in the screenshots below, how painstaking and time-taking popes of the past have been in this regard.

Which makes my criticism of the USCCB (Modern Catholic), particularly its treatment on “fasting,” all the more palpable. That criticism is linked in Tuesday’s piece as well.

Jerome did not reject the Septuagint out of simple hostility or some silly belief that no one would “catch him,” particularly given the centrality of the Septuagint to Christian thought, which Walt aptly illustrates. Rather, as recent scholarship explains, Jerome–unusually for his time–learned Hebrew, consulted Jewish scholars (which admittedly makes me flinch), and set himself the painstaking task of bringing Latin readers as close as possible to the original texts he believed lay behind the Scriptures–which preceded the Greek translation. From my understanding, he wanted to skip the filter of the Greek translation of the original Hebrew and go straight to the Hebrew itself, primarily because he was now translating it into Latin. So essentially, it seems to me, he was doing the same thing, just in Latin and not Greek.

(Also understand that we are not dealing with a version of Hebrew which would come much later, far after Jerome, which conflates the understanding even more when it comes to more recent Bible printings. It’s confusing, I know).

For parts of the Old Testament where Hebrew witnesses were available, Jerome preferred to translate iuxta Hebraeos–according to the Hebrews–rather than simply copy the prevailing Greek versions; in prologues and prefaces he explains his reservations about certain Septuagint readings and extra books. I’ve included examples and links to all of that here.

Jerome’s turn toward Hebrew seems to be a scholarly effort to recover a particular textual lineage and to correct what he judged to be Hellenizing interpolations or corruptions–yet his work did not erase the Septuagint’s primary role in the early Church. Appreciating both witnesses in my estimation is the mark of responsible textual fidelity, and as the screenshots below will show, a realization that errors can creep into translations over the decades and centuries for most any reason.

That said, the Septuagint remains vitally important. As numerous studies show, including some basic online searches, the Greek translation routinely preserves readings and textual traditions that illuminate an earlier stage of the Hebrew text and the way the Old Testament was received in the centuries immediately before and after Christ–something Walt makes clear. The New Testament authors frequently quote the Septuagint, and for many early Christians the Greek text was their Bible. The Septuagint therefore functions as an indispensable witness in textual criticism and theology–perhaps especially when it diverges from later Hebrew.

The Catholic Church, even the Modern one (I think), recognizes that. The Douay-Rheims English translation most certainly does.

The Douay-Rheims Difference

Putting these pieces together gives us a more nuanced historical picture than a simple “Vulgate ok/Septuagint better” binary. It is what, in my opinion, furthers the unnecessary divide between East and West, a topic I believe Walt knows I study and pray about.

For English-speaking Catholics seeking continuity with the Church’s Latin tradition, the Douay-Rheims represents a direct reception of Jerome’s Vulgate into English. It preserves the Vulgate’s phrasing and theological emphases in a way that newer vernacular translations–often based on varied Hebrew and Greek critical texts as I understand it–do not always replicate. Certainly the Scofield English versions should be off limits. For readers committed to liturgical and doctrinal continuity, the Douay-Rheims (and editions with traditional Catholic commentary) remain a helpful corrective to modern casualness about textual presentation and reading.

As I said above, some simple word choices may very well change your life, your entire understanding of your faith, as “Do penance” and “God’s justice” has for me.

Toward the end of his piece, Walt writes the following:

The upshot of all of this is that, if someone is going to pick up a Bible to read, he needs to make sure it is based on the Septuagint version of the Scriptures. The Latin Vulgate, like the English King James Version or the Welsh Bible, has contributed good things to Christendom. But the testimony of the Church Fathers tells us to prefer those translations based on the Septuagint, as it is God-inspired and therefore the most accurate.

To me, this is where the true divide in our articles lies. I will mostly allow you, reader, the freedom to choose, except for two points I’ll make in a moment. Consulting the internet directed me to Bibles inspired by the Septuagint, one of which I am assuming Walt consults, which indeed illustrates the split between Orthodoxy and Catholicism. In other words, it makes sense that Walt is going to bat for the Septuagint. It also makes sense that I as a Tradition Latin Catholic am going to bat for the Vulgate.

Two specific things I’ll say on the above pull quote…

The Douay-Rheims was not just another English Bible–it was the Catholic rebuttal to Protestant distortion, intrinsically encouraged and spread by the King James. Remember, before 1969, all of Catholicism was known to be “Latin” as a form of mental shorthand. It was a given, not something someone like me has to distinguish with such repetition today. To bracket it with the King James, as if they were theological cousins, risks obscuring that reality. Perhaps Walt was working to make another point, but my clarification needs to be considered as well.

This is a simple and perhaps useful site to get more surface level information on the Douay-Rheims:

Though published only a year apart, the Douay Rheims Catholic Bible and the King James Bible reflect entirely different theological commitments. The Douay Rheims, rooted in the Vulgate and Catholic doctrine, was designed to teach the faith clearly and defend it against error. The King James Version, translated by Anglican scholars, relied on Hebrew and Greek sources filtered through a Protestant lens. While both Bibles share a majestic English style, they diverge sharply in meaning. The Douay Rheims remains faithful to Catholic tradition, while the King James often modifies or omits elements crucial to Catholic belief.

In other words, the Douay-Rheims is more a direct response to Protestantism, not Orthodoxy.

The other thing I’ll say in direct response is that, as the Preface/screenshots below contends, particularly in conjunction with everything we’ve discussed here concerning text transfer over the centuries, can we assert with certainty that a translation of a text–as it is when it reaches a reader’s eyes–is truly God-inspired? The Preface below argues that only the original language and text can claim as much with confidence, given the numerous obstacles involved in translation, transfer, and time. Walt may be right, most certainly, but I invite you reader to consider what this Preface–in stunning humility I might add–admits.

OTHER VOICES: Everything You Need to Know About the Douay Rheims Catholic Bible

In the end, I offer that the Septuagint and the Vulgate are both indispensable witnesses, as both St Jerome and the Catholic Church attest. Jerome’s skepticism about certain Septuagint readings arose from a pursuit of textual fidelity, seemingly to the same Hebrew the Greeks translated with fidelity centuries prior, not from an impulse to dismiss the Greek tradition entirely. After all, at the time of Jerome, the Church–East and West–was united. In the end, from my perspective, reading the two Hayride pieces, and now a third, with nuance clarifies how translation choices shape theology–and why Christians ought to choose their Bible with both care and charity. Doing so may also offer a glimpse into the elements that keep unification from actually occurring, and perhaps lead us to a unification of the single Church Christ commanded.

All of that said, and I know it was a mouthful, if the choice is between Walt’s trust of the Septuagint or a Scofield-poisoned text, indeed, the choice is obvious–and I believe Jerome himself would agree.