Could Australia Lead the Way to Facial Recognition Reforms?

A new report from the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) Human Technology Institute outlines a model law for facial recognition programs to protect against harmful use of this technology, but also foster innovation for public benefit.

Led by UTS Industry Professors Edward Santow and Nicholas Davis, the report, Facial Recognition Technology: towards a model law, recommends reform to modernize Australian law, which does not yet include provisions for facial recognition technology. The proposed updates to the law would address threats to privacy and other human rights.

The initiative by the two professors coincides with widespread calls for reform of facial recognition law, not only in Australia but throughout the world.

Based on a report by the BBC, Australia was the only democracy that used facial recognition technology to aid Covid-19 containment procedures — while other countries were pushing back against the idea of employing such surveillance.

In May 2019, San Francisco was the first U.S. city to introduce a moratorium against police using facial recognition. That decision was followed by similar votes in Oakland, California, and Somerville, Massachusetts.

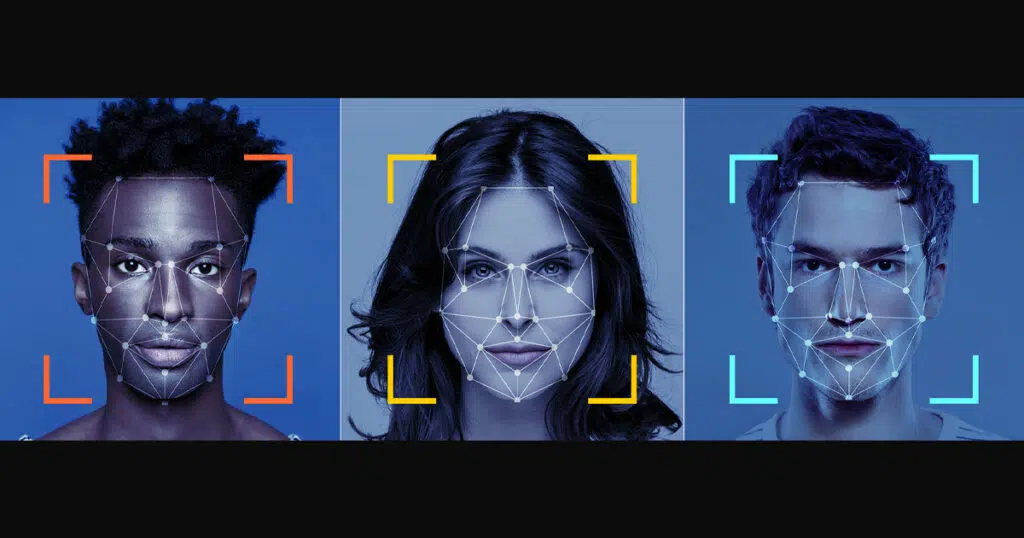

Facial recognition and other remote biometric technologies have experienced explosive growth in recent years, raising concerns about privacy, mass surveillance, the potential misuse of the enhanced programming and systemic biases suffered by people of color, women, and those of other marginalized populations when the technology makes mistakes.

In June 2022, an investigation by consumer advocate CHOICE revealed several large Australian retailers were using facial recognition to identify customers entering their stores, leading to considerable community alarm and calls for improved regulation.

This new report responds to those calls. It recognises that human faces are special, in the sense that people rely heavily on each other’s faces to identify and interact. This reliance leaves us particularly vulnerable to human rights restrictions when this technology is misused or overused, explained Santow, former Australian Human Rights Commissioner and now Co-Director of the Human Technology Institute.

“When facial recognition applications are designed and regulated well, there can be real benefits, helping to identify people efficiently and at scale,” he said. “The technology is widely used by people who are blind or have a vision impairment, making the world more accessible for those groups.”

The report proposes a risk-based model law for facial recognition, where the starting point should be to ensure that facial recognition is developed and used in ways that uphold people’s basic human rights, Santow said.

“The gaps in our current law have created a kind of regulatory market failure. Many respected companies have pulled back from offering facial recognition because consumers aren’t properly protected,” said Davis, a former member of the executive committee at the World Economic Forum in Geneva and Co-Director of the Human Technology Institute.. “Those companies still offering in this area are not required to focus on the basic rights of people affected by this tech,” he said .

“Many civil society organisations, government and inter-governmental bodies and independent experts have sounded the alarm about dangers associated with current and predicted uses of facial recognition,” Davis added.

The report calls on Australia’s Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus to lead a national facial recognition reform process. This should start by introducing a bill into the Australian Parliament based on the model law set out in the report.

But the report also recommends assigning regulatory responsibility to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner to regulate the development and use of this technology in the federal jurisdiction, with a harmonized approach in state and territory jurisdictions.

The model law sets out three levels of risk to human rights for individuals affected by the use of a particular facial recognition technology application, as well as risks to the broader community.

Under the model law, anyone who develops or deploys facial recognition technology must first assess the level of human rights risk that would apply to their application. That assessment could then be challenged by members of the public and the regulator.

Based on such a risk assessment, the model law would then set out a cumulative set of legal requirements, restrictions and prohibitions.