Hopefully, NASA’s Asteroid Probe Will Crash And Burn Tonight

At 7:14 tonight Eastern Time, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) will lose a $324-million automated space probe, as it crashes into one of the asteroids orbiting our sun between the planets Mars and Jupiter.

That’s if everything goes well.

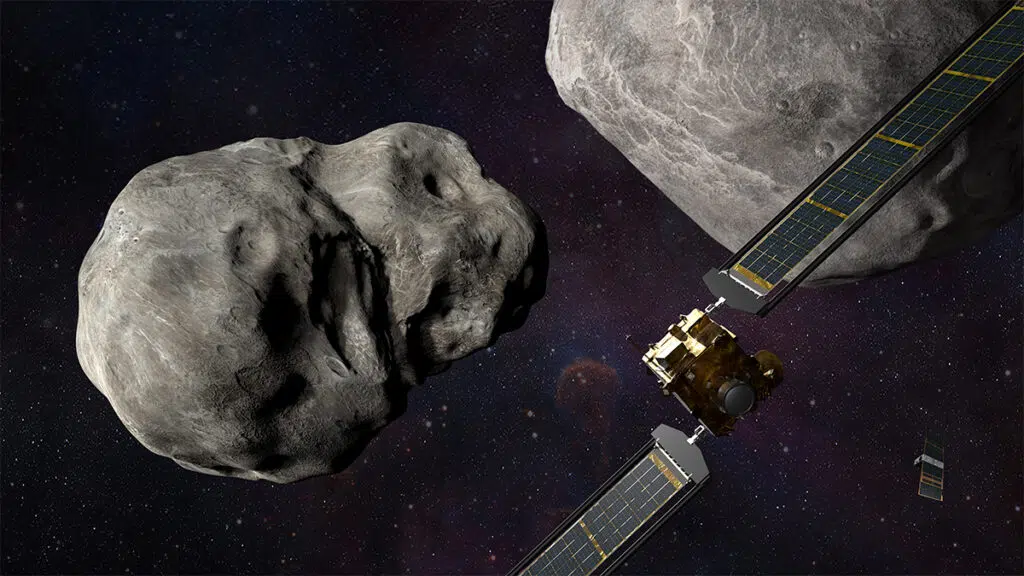

Since its beginning, the agency’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission has had the goal of crashing its spacecraft into Dimorphos, a small moonlet orbiting a larger asteroid, Didymos, to measure the affect of the impact on the larger body’s overall trajectory. While the asteroid poses no threat to Earth, this mission will nonetheless test technology that could be used to defend our planet against potential asteroid or comet hazards that may be detected in the future.

Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, designed and leads the mission for NASA. But as with many projects, the DART mission has required expertise from other NASA centers, in the case of the agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California,which offers extensive knowledge in probe navigation, locating the precise location of the target, asteroid science and Earth-to-spacecraft communications.

“Strategic partnerships like ours with APL are the lifeblood of cutting-edge space mission development,” said Laurie Leshin, director of JPL. “Our history of working with APL goes all the way back to Voyager and extends well into the future, with missions like Europa Clipper. The work we do together makes us all – and our missions – better. We’re proud to support the DART mission and team.”

Launched in November 2021, the approximately 1,320-pound (about 600-kilogram) DART spacecraft will be at a point 6.8 million miles (11 million kilometers) from Earth when it impacts Dimorphos, which is just 525 feet (160 meters) across.

Making the mission more challenging, the spacecraft will be closing in on the space rock at about 4 miles (6.1 kilometers) per second. Dimorphos orbits Didymos, which is roughly half a mile (780 meters) in diameter.

JPL’s navigation section is experienced at getting spacecraft to faraway locations accurately — think Cassini to Saturn, Juno to Jupiter, Perseverance to Mars. Each mission brings its own set of challenges, and DART has many.

“It’s a difficult job,” said JPL’s Julie Bellerose, who leads the DART spacecraft navigation team. “A big part of what the navigation team is working on is getting DART to a 9-mile-wide (15-kilometer-wide) box in space 24 hours before impact.” At that point, Bellerose said, the mission’s final trajectory correction maneuver, which will require the probe to fire its thrusters to modify the direction of flight, will be executed by mission controllers back on Earth. Then, it’ll up to DART itself.

During the final hours of its one-way journey, DART will utilize an autonomous onboard navigator created by APL to stay on course, using SMART Nav, or Small-body Maneuvering Autonomous Real Time Navigation. the program collects and processes images of Didymos and Dimorphos from DART’s DRACO (Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation) high-resolution camera, and then uses a set of computational algorithms to determine what maneuvering will need mto be done in the final four hours before impact.

Along with the DART team, another group of JPL navigators will be calculating and planning the trajectory of DART’s spacecraft companion, that includes the Italian Space Agency’s (ASI) Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging Asteroids, or LICIACube, which is tasked with imaging the effects of DART’s impact effects on Dimorphos. The toaster-size imaging spacecraft disconnected from DART on Sept. 11 to navigate interplanetary space on its own – with an assist from the team at JPL.

“We are working with ASI to get LICIACube to within 25 to 50 miles (40 to 80 kilometers) of Dimorphos — just two to three minutes after DART’s impact – close enough to get good images of the impact and ejecta plume, but not so close LICIACube could be hit by ejecta,” said JPL’s LICIACube navigation lead Dan Lubey.

While not necessary for the DART mission to succeed, the pre- and post-impact images provided by the LEIA (LICIACube Explorer Imaging for Asteroid) and LUKE (LICIACube Unit Key Explorer) cameras could greatly benefit the scientific community in studying near-Earth objects and aid in the interpretation of the DART results.

JPL’s Center for Near Earth Object Studies (CNEOS), part of NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO), was given the responsibility of not only determining the location of Didymos in space, give or take 16 miles (25 kilometers), but also specify when Dimorphos would be visible – and accessible – from DART’s direction of approach.

Along with investigators at other institutions, members of CNEOS will study the plume of rock and regolith (broken rock and dust) ejected by the impact, as well as the newly formed impact crater and Dimorphos’ resulting orbit around its parent asteroid.The JPL team will not only examine data and imagery from DART and LICIACube, but also data from space and ground-based telescopes.

Scientists think the impact should shorten the moonlet’s orbital period around the larger asteroid by several minutes. That duration should be long enough for the effects to be observed and measured by telescopes on Earth. It should also be enough for the test to show whether impacting an asteroid to adjust its speed and therefore its path could, in fact, protect Earth from an asteroid strike.