Out on Private American Patrols in the Smuggler-Blighted Border Badlands of Arizona

CORONADO NATIONAL FOREST, Ariz. – As blazing sunlight ebbs to a star-studded sky along the U.S.-Mexico border, members of the Arizona Border Recon group peer through field glasses at a trio of men on the southern side in camouflage fatigues and carrying pistols and AK-47s.

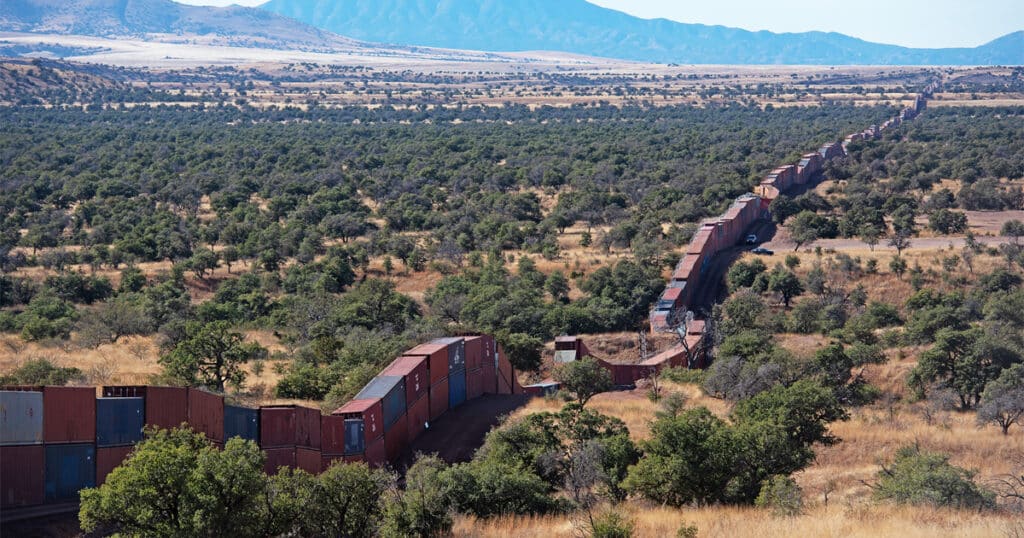

The men, almost certainly members of Sinaloa cartel factions, are using their own binoculars to scan random gaps in a roughly 30-foot-high wall of thick metal bars that stretches for miles along a flatland carved by arroyos and dotted with rocks, saguaro cactus and high grasses. At times, a solo gunshot echoes on the Mexican side, a sound the AZBR knows from experience is a signal to people to start moving north.

There are chiefly two types of people AZBR teams have encountered filtering into the United States. Some of them carry packs filled with canned food, cookies and blankets. But others trek lugging much larger packs and no such rations or equipment – indications their cargo is a more illicit sort.

The AZBR is a private group with no authority to arrest the mules, but for years its members have run patrols and cameras along the hundreds of trails and washes that web an area the group has dubbed Baby’s Head Gap. It is so named for a Mexican doll’s head atop a spike in the desert, an apparent warning to anyone wanting to cross that passage is done only with the cartel’s permission.

The uneven landscape, with ravine ridges marked by trees and bushes running along the top, offers low visibility for Sinaloa cartel agents carrying fentanyl, as well as for AZBR teams out on days-long operations during which they share intelligence and photos with U.S. officials.

The presence of U.S. authorities in this open, gashed wasteland is light; on a recent operation AZBR members saw an occasional Blackhawk helicopter dart across the sky, but there were no foot patrols. At least in the area they patrol, AZBR leaders agree with former U.S. Border Patrol Chief Rodney Scott, who told a House committee on May 23 that Mexican drug cartels “control everything that crosses that Southwest border,” including “illegal migrant crossings” that “create gaps in border security.”

Because they have no law enforcement power and carry weapons only for self-defense, AZBR members are more witnesses to the disintegrating border than a force of deterrence.

The private group was founded in 2011 by Tim Foley, 64, a former 82nd Airborne paratrooper and recovering addict whose endless gulping of cans of Red Bull and chain-smoking of American Spirit cigarettes put a modern twist on Spartan habits.

“I live almost solely on caffeine, nicotine and an occasional Pop-Tart,” he said.

Foley knows cartel members control the Mexican land he watches because in January 2022, he says, they contacted him, via a phone call from a federale, a Mexican state police officer. The caller initially offered to furnish AZBR with “any gear or weapons, gifts,” which would mean “you wouldn’t be our enemy then.” Foley declined and two weeks later the man called again, this time offering $15,000 a month if AZBR would cease operating.

Again, Foley said, he declined, at which point the federale sighed and told him that, in that case, the cartel was going to raise the price on his head from $100,000 to $250,000, a rich bounty that luckily no one has collected.

On a recent AZBR patrol in mid-May, menacing silhouettes appeared on the southern skyline. These cartel members are soldiers of a sort themselves – infantry in the drug trade that has seen the Southwest borderland become the main conduit for deadly fentanyl, according to federal prosecutors and law enforcement officials with whom Foley is in regular contact.

While much of the border attention has fallen on Texas, authorities in Arizona seized at least six tons of fentanyl at the entry point of Nogales in just four months between October and January. Two March busts there found more than 560,000 fentanyl pills, according to federal officials. The March seizures involved vehicle and tire smuggling operations, which the cartels use to move the largest stashes of fentanyl, but individual carriers are also involved.

For a decade now, Foley has had numerous encounters with migrants, and with cartel members – sometimes armed. While AZBR has a mailing list of 50, his intelligence-gathering missions involve no more than a dozen vetted volunteers, about the size of a Marine Corp infantry squad.

Some of them, like Foley, are ex-military, including a former Green Beret. They camp and run trail cameras in high-traffic areas where migrants and smugglers regularly traverse the treacherous desert seeking a new life, or a drop-off point for the contraband they have carried into the U.S.

“The beginning was hard, as I had to learn the terrain and the tactics of what was going on down here,” Foley said. “I started out with five others, but they faded away in about six months. Around a year later, AZBR was officially started.”

The AZBR team members take time off work, and away from their families, to come out to the border and obtain intelligence to share with the U.S. Border Patrol. Some come from nearby Tucson, others farther away. With the use of volunteers on the ground, cameras on the trail and drones in the sky, they regularly observe the movement of the cartel and their mules on the south side and north side of the U.S. border.

Foley notifies his network of federal and local law enforcement contacts before AZBR teams head out, indicating where they will be operating. Some members speak Spanish, including Foley’s number two, Enzo, the better to communicate during encounters with strangers in the baked wasteland.

Sex Work Looms for Indebted Young Women

Over the years, AZBR patrols have seen countless drug mules, human smugglers, migrants and even dead bodies – some victims of the cartel, others victims of mother nature. Last November, an AZBR team encountered two young women who startled the team by saying they had paid no one to cross – an unheard-of arrangement in a world where the cartel routinely charges between $3,000 and $5,000 for the crossing. The women said they were simply told to meet up with a man in Tucson, leading AZBR to speculate the women and their unrealized debt could lead to sex trafficking.

In that case and others, AZBR will notify Border Patrol officials, who come and take the crossers into custody. Foley is explicit in saying he does not want “cowboys” on his operations – AZBR is not looking for confrontations or shootouts and does not view itself as a law enforcement group.

Anger over border crime is one motivating factor for some AZBR members, who prefer to remain anonymous. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the Border Patrol did not respond to a request for comment about the group’s activities.

Still, the members know how they are sometimes perceived. In articles about them published by Soldier of Fortune magazine and then posted on social media, some commenters deride AZBR members as wannabes or “LARPs” – live-action role players. They shrug at the labels, all of which they reject.

“We’ve been called everything in the book – ‘militia,’ ‘vigilantes,’ ‘domestic extremists,’ and the list goes on,” Foley has said. “We are an NGO; we have no ranking structure and my official title is field operations director. The only rank in the organization is my dog, Sgt. Rocko, and that’s just because it sounds cool. What we’ve never been called is ‘neighborhood watch,’ but this is my neighborhood and I’m watching it.”

Some migrants who have entered the U.S. illegally have mistaken AZBR volunteers for government officials and tried to surrender to them. More often, they are led a few hundred meters into the U.S. and then abandoned by the cartel coyotes who promised to get them to Tucson, about 70 miles away.

With no help, they will die of exposure quickly, but AZBR provides food and water while waiting for the Border Patrol to pick them up. In terms of drugs, AZBR has found several kilos of dope in stashes near Arivaca, Ariz., and on cartel mules in the U.S. The patrollers’ practice is to immediately notify Border Patrol and turn over the contraband.

While two square miles is but a postage stamp on the Southwest border, it is an immense area for small teams to patrol and Foley is under no illusions about what is happening there or AZBR’s ability to make a major dent in the traffic.

“I have no regrets, only frustrations,” he said.

Open borders opponents are also frustrated with the way President Biden began lifting immigration restrictions the moment he took office in January 2021. Arizona sued Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, who has supervised the Biden administration policies of paroling hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers, to keep in effect Title 42, a COVID-related border restriction launched by the Trump administration.

On May 18, however, Arizona’s case was rejected by the Supreme Court, with Justice Neil Gorsuch ruling the government cannot apply an emergency decree for one crisis, COVID, to another, illegal immigration. Gorsuch also used his rejection to write a ringing rebuke of the way government trampled on civil liberties during the epidemic, strictly enforcing ruinous economic shutdowns and made-up steps like social distancing that have since proven ineffective in fighting the virus.

Another court case filed by Florida, however, has been more successful in trying to curb the Biden administration’s efforts to relax border controls and facilitate the passage of more immigrants. While the figures for May when Title 42 ended have not been compiled, monthly records for illegal crossings have been set and shattered repeatedly under Biden.

In April, U.S. Customs and Border Patrol had 211,401 encounters at the Southwest border, up 10% from March and 20% more than they encountered in April 2022. The Southwest border accounts for more than 85% of port-of-entry encounters, which can include recrossing illegal immigrants but does not account for “gotaways,” those that Border Patrol agents do not see. More than 5 million people are estimated to have now entered the U.S. across the Southwest border during the last 2½ years.

Numbers like that and the skyrocketing fentanyl overdoses in the U.S. can make the work of AZBR volunteers seem inconsequential. But this does not dissuade them from what they see as their duty to protect the small sliver of the U.S. border that they consider their “backyard.” The hope is that the U.S. government will deploy more federal agents to the border to quell the surge, but it may take the efforts of citizens working alongside federal authorities to disrupt the flow of illegal drugs and migrants into the United States.

Foley, for one, has developed a fatalistic outlook from what’s happening.

“I never thought I’d be here this long, but here I am,” he said. “I told myself there’s only two ways I’d leave here. One, if I felt it was safe and secure; or two, if I died. From the way things looks, it’ll be the second one.”

This article was originally published by RealClearInvestigations & Soldier of Fortune and made available via RealClearWire.