Nolan’s Visual Power Unleashed in ‘Oppenheimer’

“It is an atomic bomb. It is the harnessing of the basic power of the universe,” declared President Truman after the bombing of Hiroshima. Christopher Nolan’s latest hit Oppenheimer harnesses the acclaimed director’s visual power to offer a masterful interpretation of one man’s hubris, self-delusion, and inner turmoil as he recognizes the terrible force he has helped unleash. By focusing on the human at the center of the story, Nolan’s film avoids his usual shortcomings and delivers complex commentary on this moment in history and its implications for our era.

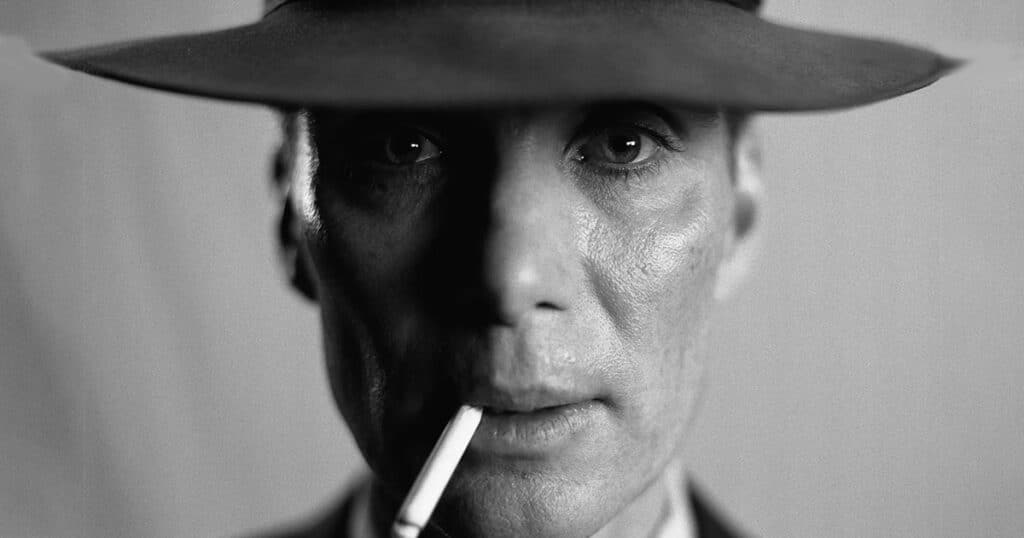

Nolan finally matches his visuals with a terrific script and piercing analysis of human nature. This is something he failed to achieve in films like The Prestige or Inception, both of which offer visual appeal but lack a deeper human story. With the help of compelling dialogue and Cillian Murphy’s fierce gaze, Oppenheimer’s titular character delivers the heart missing from Nolan’s previous work.

The visual language that Nolan offers unfolds the raw power of the bomb and the inner mind of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer dreams as a graduate student of the new power discovered within the atom and brings new physics back with him from his studies in Europe. He pictures how the arcs of electrons in their atomic orbitals mirror stars and planets. He sees the sparks of a fire evoke the subatomic particles all around him. The potential power of the atom, seen through the daydreams of a graduate student, is later contrasted with the all-consuming fire of the Trinity test — the first nuclear detonation in history.

These images reflect the protagonist’s lust for power. As the leader of the Los Alamos center for the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer holds immense influence over political and military leaders. After the bomb is successfully built and tested, we see the trucks carrying the two bombs out of the compound. As they cross from the impromptu lab in the desert into the control of the military, we see Oppenheimer deflate. When he asks the ever-practical Leslie Groves to keep him informed of the date of the drop, he is rebuffed. He has no power over the bomb; he has become merely a man.

This humanity is on full display in Oppie’s foibles, pride and character flaws. “Genius is no guarantee of wisdom” a character remarks, and Oppenheimer fulfills the prophecy repeatedly. He carries out a compromising affair. He alienates his colleagues one by one. His conscience, once seared, influences his actions only after he gains his fame and procures his power. He believes that his fame and intellect will protect him. The paradox of self-delusion, continued from Nolan’s early film Memento, is mirrored here in the insights of theoretical physics, the teaching that light is simultaneously a wave and a particle. Does Oppenheimer want credit for the invention of the Atomic Bomb? Surely he wants credit for the scientific advances, but not the responsibility, and thereby guilt, of its after-effects.

In case we are tempted to villainize Oppenheimer, Nolan carefully and deftly draws out this fatal flaw of hubris in every major character. That should be our main interest in the film: not that it shows an aberration of human character, but that it reveals something universally true about each of us.

Odds are no one reading (and certainly writing), this article is a genius, but the temptation always exists to elevate ourselves through whatever limited powers we possess. Declining to use that power is one of the most difficult things any of us will face. That is another paradox set forth by Nolan: We each possess powers that we must choose to leave unemployed. Some latent powers should not be exploited. The power of the atom is arguably one such power. Once the technology was created, it would be used for pragmatic reasons.

J. Robert Oppenheimer stands at the turning point of modern history, from an optimistic view of human nature and technology’s role in “solving” it and the turning point of a collective loss of faith in progress. Nolan reveals how the atom bomb’s ignition unveiled not just a new technology, but a new world. Military leaders and historians will debate endlessly whether it was justified to drop the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but Oppenheimer embodies the doubt as to whether scientists should have unleashed this force at all.

The splitting of the atom also becomes the physical embodiment of our fragmenting world. New inventions are inevitably touted as a solution to a fundamental human woe. Just as social media promises to connect, the atomic bomb promised the end of all war. This is not to say that human ingenuity cannot ease some of our momentary discomforts. Technological progress can increase our life expectancy and make us more comfortable, but it cannot change our fundamental human frailty.

Oppenheimer’s heroism stands out in his tenacity and ingenuity in bringing a theory into reality through his leadership in the Manhattan Project. But the film also stands as a warning of how humans will use any innovation towards their own ends. “Man’s power over Nature,” C.S. Lewis argues in The Abolition of Man, “turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument.” That is the true genius within Oppenheimer, that through the story of one man it turns a mirror on our lives and forces us to grapple with the consequences of innovation.

Noah C. Gould writes widely on culture, economics, and business. His writing has appeared in publications including Religion & Liberty, The Detroit News, and National Review. He is the Alumni & Student Programs Manager at the Acton Institute and a Contributor for Young Voices.

This article was originally published by RealClearBooks and made available via RealClearWire.