World War II and the Story of Herman Kuhnle, Louisiana POW

Editor’s note: This entry was originally published on Oct 11, 2017 as part of my work towards an MA in History at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. My days pouring over primary documents in the Special Collections room in the library was one of the most fruitful and frightening times in my lifelong acquisition of knowledge. It is truly mind-numbing to consider how much real history never makes it to government controlled textbooks. The series started on Memorial Day with the following post and continues with a second component on POW Herman Kuhnle.

World War II and Life and Labor in the Louisiana POW Camps

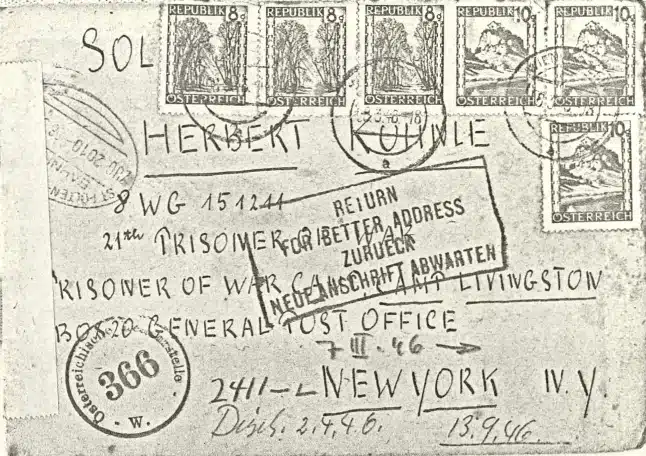

Herman Kuhnle made stops at four Louisiana camps: Livingston, Houma, Donaldsonville, and Port Sulphur. He was born in Vienna on 13 June 1926, so he was 18-19 years old at the time these treasures were produced.

He was drafted at age 17 and sent to a place near Toulouse for training. He was captured by Americans with about seventy others, after which commenced a series of heavy skirmishes and bombing. After three difficult days where they all feared for their lives, they were marched through mountains to shore, where they camped. From there they were taken to Oran, where he wrote his mother.

Fourteen-hundred prisoners of war and twenty-five guards sailed off, and they were at sea for seventeen days. Early on, two or three POWs jumped. He heard shots, but never saw anything. On the journey, there was some fighting, shots heard, and alarms. Herman discovered he could communicate in English.

They arrived at Chesapeake Bay at 6pm and saw the lights from the shipyards.

“We couldn’t imagine,” Herman would later say, “what should happen to us ahead.”

He was interrogated for three hours, and later, for twenty minutes. After processing in which all of his pictures and personal effects were taken (given back one year later), he spent three days in a Pullman railroad car. He talked with a guard, listening to the radio, where they learned that President Roosevelt “was dyed” (sic). At the last station they “had to leave the car,” said Herman. “Guards were armed with machine guns. A lot of them were all so irritated as we would be wild animals. We had to put our arms hands (sic) up, were loaded to trucks and reached Camp Livingston.”

He would like Livingston. Nice clothes. Good food. Nice guards.

At one point some time later, he went by truck to empty the meadow behind some blacks’ houses to set up the Houma branch camp. “We made the fences, the water systems, electrical installations, etc.,” Herman said. He then worked in the cane fields at McCollam Bros. as an interpreter and as a driver of the loading crane. One of these McCollams later visited him and his family in Vienna. After the war, Herman wrote a farmer he had had an argument with, apologizing, and the farmer promptly sent back care packages.

Some isolated memories Herman has are that the guards were lenient, that he danced with a black girl at a cafe, that he held a guard’s rifle while the guard went into the cane field to relieve himself, that they made liquor, that some camps flew the Nazi flag, that he was punished for causing trouble once, that he received mail, that he read Life and other magazines, that he borrowed the NY Times from a guard every day, that he translated the report of German Army Headquarters, that a typewriter was provided to him, and that the sun could be extremely hot.

Herman was repatriated via France on 23 March 1946. He had been taken from America to a land of snow and smaller food rations. He lost a lot of weight during his time in France, which had been devastated by the war and couldn’t offer the same amenities America did.

**See the fascinating historical photographs I used to enhance the above writing**

Bio compiled by Jeff LeJeune from information found on single information sheet in Box 2, Folder 2-31 of the UL-Lafayette Special Collections