Supreme Court Considering Ending Racially Drawn Electoral Districts

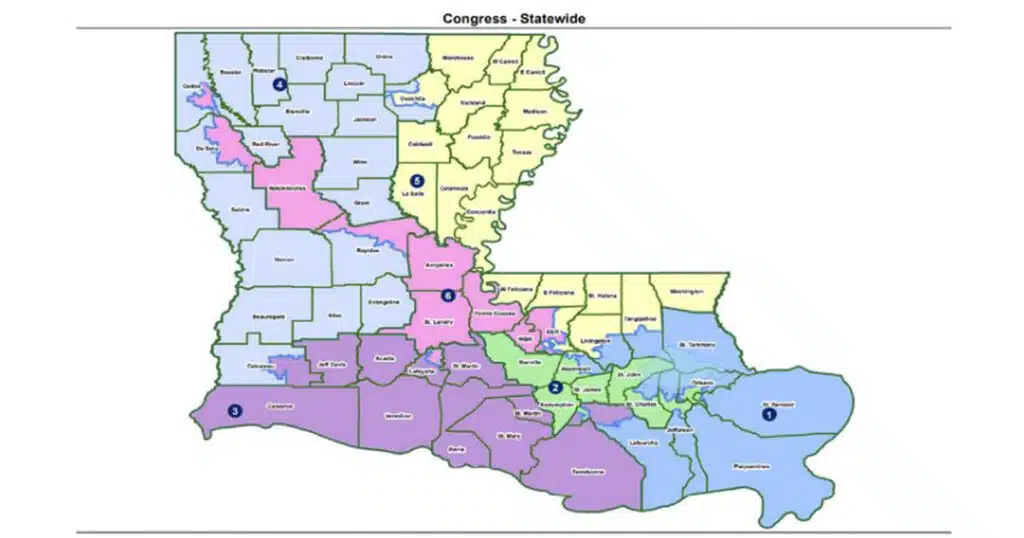

The Supreme Court has asked a question long deferred: may race be the predominant factor in drawing congressional districts? On August 1, 2025, in the case of Robinson v. Ardoin, the justices issued an order for supplemental briefing on precisely that issue. At the heart of the case is a map in Louisiana, which connects disparate Black communities across the state to create a second majority-Black district. The method is undisguised: race was the reason for the shape. The rationale? Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act requires it. But does it? And if so, is Section 2 itself unconstitutional in its current interpretation?

This moment offers an opportunity to resolve a contradiction at the core of American election law. States like Texas, currently advancing a new map that adds five Republican-leaning districts, now face legal crossfire: if race is not considered, they risk violating Section 2. If it is considered, they risk violating the Equal Protection Clause. One branch of federal law demands race-consciousness, another forbids it. The state is expected to perform a legal contortion that no theory of jurisprudence can justify and no mapmaker can survive.

Let us be clear: race-based redistricting, as presently practiced, is not a civil rights triumph. It is a vestige of a failed doctrine, preserved by inertia and political convenience. Its intellectual foundation is cracked. Its moral justification is confused. And its legal coherence has long since collapsed.

The Court has spent three decades attempting to split the atom of race and districting. In Shaw v. Reno (1993), it held that districts shaped predominantly by race are presumptively unconstitutional. But it also held, implicitly, that racial consideration is sometimes required. In Miller v. Johnson (1995), the Court offered a test: race must not “subordinate traditional race-neutral districting principles.” But this is not a rule. It is a riddle. What is a “traditional principle”? Compactness? Contiguity? Political advantage? And what counts as subordination? The problem is not that these questions are difficult. The problem is that they are incoherent.

The jurisprudence of redistricting now revolves around motive rather than effect. A district that looks racially gerrymandered may survive if the court believes the motive was partisan, not racial. Conversely, a district drawn for racial balance may fall, even if it resembles an acceptable partisan gerrymander. In Cooper v. Harris (2017), North Carolina drew districts nearly identical to earlier ones that had passed muster. The Court struck them down. Why? Because the motive had shifted. Thus, the map itself is less important than the state of mind of the mapmaker. This is not law. It is psychoanalysis.

Justice Clarence Thomas has long warned that Section 2, as interpreted, has become an engine of racial sorting. In Allen v. Milligan (2023), he argued that the VRA “requires the very racial sorting the Constitution forbids.” The law demands that states guarantee minority opportunity, which in practice means drawing majority-minority districts. But achieving this requires treating citizens not as individuals, but as representatives of racial blocs. It is, in effect, racial apportionment. And it is incompatible with the Fourteenth Amendment.

Some will object: does not the history of racial discrimination demand corrective measures? It does. But the constitutional remedy for discrimination is the prohibition of discriminatory intent, not the imposition of racial quotas. In 1982, Congress amended Section 2 to allow liability based on disparate impact alone. This was the original sin. It created a legal regime in which even race-neutral maps can be struck down if they fail to produce proportional racial outcomes. The test laid out in Thornburg v. Gingles (1986) invites this logic: if a minority group is geographically compact, politically cohesive, and usually defeated by bloc voting from the majority, a district must be drawn to give it a fair shot. But what is a “fair shot”? In practice, it means a seat in rough proportion to population share. This is a de facto quota, no matter how delicately phrased.

To see the absurdity, consider Texas. The House Select Committee on Redistricting recently approved a new map that expands Republican strength. Critics allege that it fails to account for the state’s growing Latino population. But how should it account for it? If Latino voters are politically diverse, no single district can reflect their preferences. If they are geographically diffuse, no compact district can encompass them. And if the state avoids using race at all, it is accused of negligence. The only way to win is not to play. This is what Judge Edith Jones once called the “Kafkaesque” quality of VRA enforcement.

Louisiana’s current litigation is a perfect test case. One-third of its population is Black. In 2022, the legislature drew a map with one majority-Black district. A federal court invalidated it. The legislature responded with a new map creating a second Black-majority district, District 6, linking communities from Baton Rouge to Shreveport. It was hailed as a VRA triumph. But another panel struck it down again, calling it an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. So the same racial logic that was required under federal law became unlawful under the Constitution. The Court must now answer: can a state obey both?

The answer, if it is to be principled, must be no. Race may not be used as the predominant factor in redistricting, because doing so violates the Equal Protection Clause. The state may not sort voters by race. It may not assign political voice based on ancestry. It may not draw lines that assume, a priori, that individuals think alike because of skin color. These are the principles of a colorblind Constitution, as articulated in Parents Involved v. Seattle (2007) and reiterated in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (2023). To say otherwise is to create a racial exception to equality under the law.

And what of the Voting Rights Act? Properly interpreted, Section 2 forbids intentional discrimination, not statistical imbalance. It was meant to stop literacy tests, poll taxes, and procedural tricks. It was not meant to guarantee demographic symmetry. To restore it to its original purpose is not to gut it. It is to save it from constitutional collapse.

Critics warn that ending race-based districting will reduce minority representation. Perhaps. But if minority candidates can win only in majority-minority districts, we have already failed. The point of civil rights law is not to freeze identity groups in political amber. It is to liberate individuals from the weight of group expectations. Political equality means that every citizen’s vote counts the same, not that every group gets a seat at the table proportionate to its census count.

This Court has a chance to complete the work it began in cases like Shelby County v. Holder and SFFA v. Harvard. The logic is clear. The Constitution does not permit racial classifications unless narrowly tailored to serve a compelling interest. Proportional representation is not such an interest. Nor is political balance. Nor is group parity. The only compelling interest is the elimination of discrimination. And that does not require race-based line drawing. It requires neutral principles, honestly applied.

Texas, Louisiana, and dozens of other states now await clarity. They deserve more than a demand to “consider race but not too much,” to “achieve equality without noticing inequality,” to “mind the numbers but never cite them.” This is legal satire masquerading as doctrine. It is time the Court ended it.

Let the line be drawn, not on maps, but in the law: no more racial gerrymandering. No more euphemisms. No more paradoxes. A district should be constitutional because of what it is, not because of why it was made. That is how equal protection works. Anything else is a racial contract in disguise.