The Dire State of Our Shipbuilding Infrastructure

Background

In 2018 Congress mandated 355 combat force ships for the Navy. According to the United States Naval Institute as of October 2025, we now have 287, a deficit of 68 or 20% fewer ships than required to protect the country. Naval experts, Defense think tanks, national security strategists, members of Congress, concerned citizens and the Navy itself call for much higher numbers of ships. Rising threats in every region of the globe substantiate the demand for more ships. More ships at sea to face these rising threats can be provided from two only sources…. existing ships in commission actually ready for sea or building more new ships. Exacerbating the dangers caused by a low number of ships in commission is the fact, at any given time, a large percentage are in long-term maintenance, most of them either awaiting being worked on or if actively worked on, behind schedule. The United States Naval Institute reports that ~100 ships are deployed forward at any given time. Fleet Forces command’s goal is surge ability for another 75 ships quickly. However, they acknowledge that presently only about 50 ships could surge rapidly to join deployed forces when required. Result, today the Navy can only put ~150 ships to sea to fight our enemies around the world. The actual requirement is much more than double that. The reasons for a lack of ships is too few shipyards that build and maintain our ships. The shipbuilding industry has been seriously neglected since the end of WWII. This article will examine the infrastructure, public and private, that we have to build new ships and to repair existing ships such that they are actually deployable. A ship sitting in a shipyard waiting to be overhauled or repaired is of no use in fighting our nation’s wars. The existing infrastructure we have to both build and maintain the nation’s combatant force ships will be examined and unfortunately, the picture is not pretty.

Facilities we have for shipbuilding and repair/overhaul

Public (Government-Owned) Shipyards for Overhaul, Maintenance and Repair

The U.S. Navy has four public shipyards. They are Norfolk (VA), Portsmouth (ME), Puget Sound (WA), and Pearl Harbor (HI). These are the backbones of depot-level maintenance and modernization for nuclear carriers and submarines. All are old and outdated, originally built for the wooden and steel fleets of the 19th and early 20th centuries. For contrast, at the end of WWII, the nation had 11 public (Navy) shipyards and 60+ private shipyards, a decline to the present of 80%.

Navy’s physical plants—dry docks, machine shops, foundries, and utilities are in outdated configurations that detract from efficiency. Norfolk was established in the early 1800s; Portsmouth, founded in 1800, is the oldest continuously operating naval yard in the U.S.; Puget Sound and Pearl Harbor are more recent but likewise developed for pre-nuclear ships and are outmoded in comparison with modern shipyards in the private sector or overseas. None were designed for today’s ships, especially our massive carriers and our exquisitely complex submarines.

To Navy’s credit the Shipyard Infrastructure Optimization Program (SIOP), was launched in 2018, a 20-year plan to modernize all four facilities—reconfiguring dry docks, recapitalizing utilities, and digitizing workflow. Yet progress has been slow: the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has reported cost growth, schedule slips, and planning deficiencies. Until SIOP is complete, these yards will continue to operate under inefficient layouts, with maintenance queues contributing to fleet readiness shortfalls. It will be years before the modernization will be completed and meanwhile the fleet will be lacking the ships that are needed for today’s threat environment.

The Heritage Foundation summarizes the problem bluntly: “The four Navy shipyards as they exist today are inadequate… they have too few functional dry docks, and their facilities and capital equipment are old and poorly configured.” NAVSEA concurs, noting that the yards were “originally designed and built to build sail- and conventionally powered ships” and are “not efficiently configured” for nuclear fleets. Heritage is not some casual observer of the Navy. They do a detailed analysis annually performed by experts; most retired senior Navy personnel and they paint a very accurate picture of the Navy’s limited capabilities.

In short, the Navy’s public yards are essential but structurally obsolete—their mission limited to repair and overhaul rather than new construction, and even that function is severely hampered by antiquated infrastructure and capacity bottlenecks.

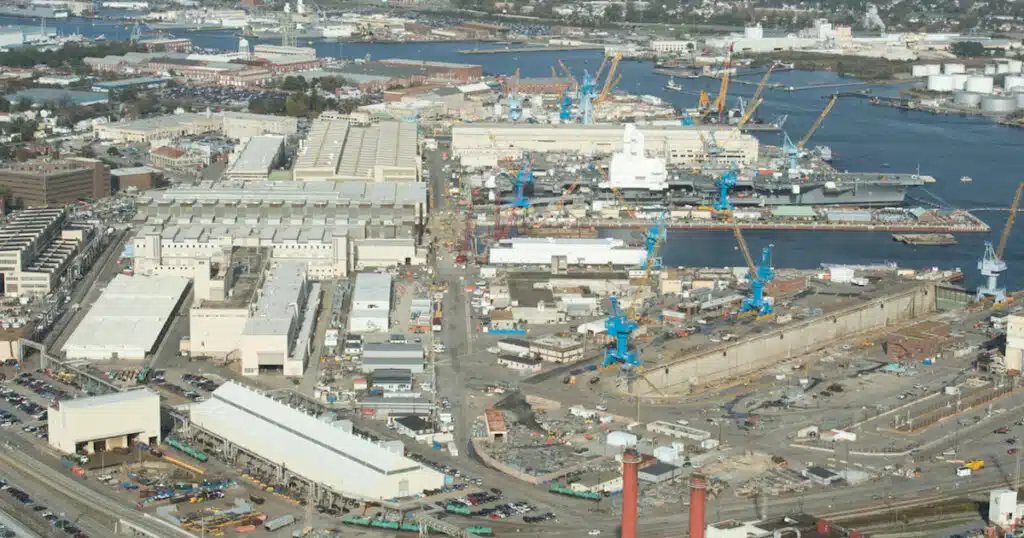

Private (Commercial) Builders: The New-Construction Base

The combatant force, destroyers, amphibious ships, carriers, submarines, and auxiliaries, is built entirely by the private sector yards. The yards are:

- Huntington-Ingalls Shipbuilding (Pascagoula, MS): Builds Arleigh Burke–class destroyers, LPD-17 Flight II amphibs, and America-class LHAs.

- General Dynamics–Bath Iron Works (Bath, ME): Co-builder of DDG-51 Burke-class destroyers.

- Huntington Ingalls–Newport News Shipbuilding (Newport News, VA): Sole builder of the new Ford-class carriers; partner with Electric Boat on Virginia- and Columbia-class submarines. Columbia class is the replacement class of our vital nuclear ballistic missile submarines, our key nuclear deterrent.

- General Dynamics–Electric Boat (Groton, CT / Quonset Point, RI): Currently building Virginia and Columbia class submarines.

- Fincantieri Marinette Marine (Marinette, WI): Building the new Constellation-class frigate.

- General Dynamics–NASSCO (San Diego, CA): Constructs oilers and expeditionary bases.

- Austal USA (Mobile, AL): Builds auxiliary and small-combatant steel ships (T-AGOS, T-ATS) and built the Independence class LCS, the last of its class being delivered in July 2025, the USS Pierre (LCS-38).

These yards are far more modern than the Navy’s public yards and equipped for modular construction, but most unfortunately remain capacity-limited. Put bluntly, they can only build a few ships at a time due to facility incapacity. Destroyer output averages roughly two per year split between Bath and Ingalls while the requirement is much higher. Through FY 2024 the Congress has authorized and funded 94 ships and only 68 have been delivered. At two per year, it will be years until the program is fully delivered. The frigate program started at Fincantieri is years behind schedule and is in extremis. Both our critical submarine programs are struggling to ramp up. Workforce shortages and lack of interest in the trades by young people, supply-chain fragility such as dependence on overseas suppliers even including China and limited dry-dock capacity keep production much slower than needed.

Despite being privately owned, most major shipyards are special-purpose naval yards, not diversified commercial shipyards. The United States has largely lost its large-scale commercial shipbuilding sector since WWII due to ill-considered policy decisions made by our government. Thus, our naval yards lack the economies of scale, modern construction methods, and steady capital reinvestment that sustain foreign peers.

America’s Obsolescence and the Modernization Gap

The contrast between U.S. public shipyards and those abroad is depressing. While America’s naval yards are steeped in history, their infrastructure remains ancient by modern standards. Studies as far back as 1972 found Navy yard production to be about 30 percent more expensive per hull than comparable private work. How we got into this situation is a long story for another day. Today, modernization is needed for every aspect: modern dry docks for Ford-class carriers, crane upgrades for submarine modules, digitized design integration, and expanded workforce availability and training in the trades.

The SIOP aims to address some of these deficiencies through roughly $20–25 billion in upgrades over two decades. Yet until those investments bear fruit, throughput at the public yards will remain a bottleneck for fleet availability—limiting how many ships can be refueled, overhauled, or modernized or repaired each year. A perfect example of this lack of capacity is the USS Connecticut. The submarine was in the Pacific on patrol in October 2021 and it collided with an undersea mount causing extensive damage. The Navy now estimates that it will not be back in service until late 2026. This is largely due to the lack of repair facilities. Over 5 years out of service for this vital submarine from this accident is a testament to our nation’s failure to be serious about what it takes to support our Navy.

Private yards, meanwhile, face the opposite challenge: limited numbers and narrow specialization. Only one yard builds aircraft carriers; only two build destroyers; only two produce nuclear submarines. With few competitors and minimal surge capacity, the U.S. industrial base lacks elasticity for rapid fleet expansion—a deadly situation for the nation’s needed “Manhattan Project for Ships” concept.

Comparison with Japan and South Korea

Industrial Scale and Modern Facilities

Japan and South Korea are the free world’s most sophisticated and technically savvy nations for shipbuilding. Both nations possess extensive commercial shipbuilding industries that build dozens of vessels annually, ranging from super-tankers to Aegis-equipped destroyers and submarines. Their defense production benefits from dual-use, military, and commercial, industrial base, ensuring continuous investment in infrastructure, automation, and skilled labor. They also have the advantage of much lower labor costs.

South Korea’s HD Hyundai Heavy Industries and Hanwha Ocean (formerly Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering) operate immense, purpose-built shipyards at Ulsan, Geoje, and Okpo. Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI), Japan Marine United (JMU), and Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI) maintain similar complexes at Nagasaki, Yokohama, and Kobe. These yards build both commercial and naval ships using highly modular, automated construction techniques with synchronized digital design.

Because their facilities are continuously refreshed through profitable commercial orders, these nations enjoy a self-sustaining modernization cycle—each generation of commercial hulls funds new cranes, dry docks, and robotics that also serve naval programs. In contrast, U.S. naval shipbuilding depends entirely on government appropriations and often operates in boom-and-bust cycles tied to congressional budgets. To complete the comparison, Japan, and South Korea account for 45% of the global market share of shipbuilding while the U.S. comes in at less than 1%.

Throughput and Efficiency

The throughput differential is dramatic. A U.S. destroyer yard typically delivers about 1.5 ships per year, whereas Korean yards of comparable scale can turn out several large combatants annually alongside commercial production. The Japanese and Korean destroyer programs—the Maya and Sejong the Great classes—are Aegis-equipped and technologically sophisticated yet constructed at a faster cadence in facilities optimized for modular assembly.

Automation, digital integration, and standardized hull modules allow these yards to reduce labor hours and cycle time, achieving consistent quality and lower cost per ton. By contrast, U.S. yards—especially public facilities—still rely heavily on older, slower processes, stagnant configurations, and aging equipment.

Structural Advantages Abroad

Why do Japanese and Korean shipbuilders have such an edge? There are multiple reasons including:

- Commercial Volume: Continuous civilian orders sustain workforce and capital upgrades.

- Modern Layouts: Dry docks, cranes, and assembly facilities are configured for modular blocks, enabling parallel work streams.

- Vertical Integration: Steel mills, component manufacturers, and shipyards operate within closely linked industrial conglomerates.

- Automation and Digital Engineering: Advanced CAD/CAM integration and robotic welding reduce errors and rework.

- Government-Industry Coordination: Both nations treat shipbuilding as a strategic national asset, aligning defense and commercial objectives.

The United States, lacking a major commercial sector and operating within a fragmented acquisition system, cannot replicate these efficiencies without major changes to the way we do business and massive investment necessarily directed by and funded by the government.

Strategic Implications

The nation’s present shipyard capability represents a major strategic vulnerability for the U.S.’s urgent need expand the fleet and the need for robust repair capacity. Public yards suffer from structural obsolescence, private yards from limited numbers and fragile supply chains and limited workforces. Together they represent a feeble industry and industrial base incapable of rapid surge production without radical reforms.

In a prolonged maritime competition—particularly against a nation like China, with enormous shipbuilding throughput—this imbalance puts the US at a distinct disadvantage. Japan and South Korea demonstrate what modern industrial shipbuilding looks like. We should look to them for insight on how to reform our capability.

Programs such as SIOP and incremental investments at private yards are needed for sure but are woefully inadequate and too slow. Closing the gap will require a comprehensive national mobilization of policy, funding, and workforce. Such a plan was outlined in my “Manhattan Project for Ships.” articles. Recommendations included:

- Dramatically accelerating SIOP timelines and fully funding dry-dock reconstruction.

- Urgently establishing new public-private yards configured for modular, high-volume naval construction.

- Dramatically expanding apprenticeship and technical-trade programs to rebuild the shipbuilding workforce.

- Government incentivizing commercial shipbuilding in U.S. yards via subsidies, tax incentives, regulatory relief and other innovative solutions copying Japan and South Korea methods to create steady throughput and capital renewal.

- Leveraging allied cooperation with Japan and South Korea for technology transfer and best practices in digital ship design and modular construction.

Conclusion

America’s shipbuilding infrastructure is in crisis and is at a historical crossroads. The four public yards—vital to sustain the nuclear fleet—are relics of the industrial age, only now entering long-overdue modernization. Private yards, though technologically advanced, are few and stretched way too thin. In stark contrast, allied shipbuilders in Japan and South Korea operate state-of-the-art complexes whose productivity and modernization far outpace the U.S.

Unless we embark on a major national renewal of our maritime industrial base, public and private, it will remain constrained in both building and maintaining the Navy required for our national defense. The U.S. must now urgently rebuild our shipbuilding industry if it hopes to restore true maritime capability in time to defend the nation from our enemies.

CAPT Brent Ramsey, (U.S. Navy, ret.) has written extensively on Defense and policy matters. He is a director with Calvert Task Group whose recent book, Don’t Give Up the Ship, was strongly endorsed by Secretary of War Pete Hegseth, Board of Advisors member for STARRS and the Center for Military Readiness, and member of the Military Advisory Group for Congressman Chuck Edwards (NC-11). He supports many other military advocacy organizations such as Flag Officers 4 America, Veterans for Fairness and Merit, the Heritage Foundation, and the MacArthur Society of West Point Graduates.

This article was originally published by RealClearDefense and made available via RealClearWire.