Leo XIV & ‘In Unitate Fidei’: The Phantom Mercy of Modernism?

My target in this article and every other like it is the contradiction and confusion all of this causes my loved ones, and the eclipse of Christ’s primacy, not the personal humiliation of individuals. I offer this analysis as a layman of the Church, not as a judge over her, and certainly not as one presuming to weigh souls. My concern here is not intent, but effect; not motives, but reception; not accusations, but clarity. I submit everything that follows to the judgment of the Church, even as I ask whether the Church’s voice is being heard as she intends. The question I return to as I write is, “Will this help a sincere Catholic move toward truth and virtue, or will it mostly inflame?” Where doctrine becomes contradiction and souls become confused, that is where I push.

And yet still, I push gently.

—

When a papal letter urges us to abandon controversies but does not define what the controversies are exactly–should we worry that “controversy” has become code for doctrinal fidelity?

When unity is presented as more important than clarity–what becomes of the deposit of faith the Church guarded for nineteen centuries?

If we accept such a redefinition now, what will we accept tomorrow as “the new faith”?

It may be that Pope Leo XIV is truly seeking evangelistic renewal, or maybe he’s providing cover for those who have long wanted the Church–which cannot be destroyed from without–to walk a different path.

Precisely to destroy it from within.

Either way, the stakes are too high to ignore.

We already know frogs boil to their deaths slowly.

A Letter and the Lens of Modernism

A week or so ago, Leo issued the apostolic letter In Unitate Fidei, commemorating the 1700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea–and calling Christians to renew their enthusiasm for the profession of faith. On the surface, without holy cunning and discernment, it reads like a noble return to fundamentals: the Creed, unity among believers, hope in a troubled world.

It reads like that. And that is the point.

The letter urges Christians to move beyond theological controversies that no longer serve the cause of unity. On the face of it, that seems reasonable–after all, who would oppose unity? But ask yourself this: When “controversy” becomes a catch-all label that includes time-honored Catholic dogma and doctrines over which secular society has always mocked us, does that not also become a tool to silence dissent and push an ever-increasing plunge to the lowest common denominator under a vague “common faith”?

An article from one “Radical Fidelity” on Substack offers worthwhile analysis, even for the most skeptical Catholic. Here is some:

Even when the text makes a theologically correct statement—that the Holy Spirit is the bond of unity in the Trinity—it applies this truth in a modernist direction. In traditional ecclesiology, the Spirit unites the Church through the visible and hierarchical means Christ established: the papacy, the episcopate, the sacraments, and the magisterium. But here, unity appears to be presented as something the Spirit accomplishes directly among disparate Christian groups, bypassing doctrinal agreement and hierarchical structure. This perspective elevates a mystical sense of unity over the visible, doctrinal unity that the Church has always insisted is essential.

The most troubling statement in the entire passage, however, is the exhortation to “leave behind theological controversies that have lost their purpose.” This raises the disturbing question: Which controversies? The filioque? Papal primacy? Apostolic succession? Transubstantiation? Justification? Marian dogmas? Every one of these so-called controversies resulted in infallible teachings defined by the Church under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Dogmatic truth never loses its purpose. To speak as if doctrinal conflicts—many of which separate Catholics from Protestants and Orthodox—have somehow expired is to propose a kind of doctrinal relativism. Here the synodalist modernist pope, or then his ghostwriter, implies that truth evolves or becomes irrelevant over time, a notion explicitly condemned by the pre-conciliar magisterium.

Under the velvet glaze and the feels of all of us “coming together,” there appears to lie an agenda: to reorient the Church’s identity not around dogma or Sacred Tradition, but around consensus, soft language, ecumenical brotherhood, and social-cultural tolerance.

Let’s all just go along to get along.

Is this true unity, or a re-branding of the perennial Faith instituted by Christ precisely to end all pagan traditions and to establish–unity?

The word “Catholic,” first coined in 108AD, actually means “universal.” Unity is the whole point–inside the Church.

Not in conjunction with it.

The letter’s dominant emphasis on journey, encounter, and walking together reflects the broader post-conciliar tendency to shift faith from an act of the intellect and will to an experience of subjective relationship–a sentiment. While such language may sound pastoral and inviting, even Christ-like because of a sprinkling of scenes in Scripture, it subtly reframes the very nature of belief and omits so many other equally important scenes. Classical Catholic teaching–clear in documents such as Vatican I’s Dei Filius–defines faith as “the assent of the will to that which is revealed by God through the Church.” When that definition is displaced by softer categories like “encounter,” and “feelings,” all of which we have illustrated at length going back to late October, the content of revelation becomes secondary to the emotion of the moment, and doctrine yields to the experience of individual persons, individual persons that make up communities, thereby subtly but substantially changing the understanding of “Catholic” in the Catholic mind.

Once the vocabulary becomes fluid, the faith it expresses becomes fluid too. And thus, by logic, what exactly is it faith in?

Ask yourself: Would Christ have wanted things to be so inconsistent, or ordered a certain way so as to maximize our chances of salvation?

The amorphous pattern continues in the letter’s heavy emphasis on humanity’s search, fragility, and shared longing, while references to sin, repentance, and divine justice all but vanish. This is typical of post-conciliar teaching–as we clearly see in the comparing the Ordinary and Extraordinary Forms of the Mass–far more in line with the “speak your truth” and “you do you” sentiments of secular culture. The concept of mercy appears repeatedly, yet in isolation from justice–a theological imbalance at the heart of Modernist instruction.

We explored that at length just last week with Francis and the notion of “weaponized mercy.” When mercy is detached from moral transformation, it becomes a tool of permission to sin rather than conversion out of it; it soothes, but does not set its foundation on more permanent sanctification. And when dialogue is elevated above doctrine, the Church’s mission subtly shifts from proclaiming truth to managing disagreement, navigating discomfort in pursuit of consensus, like an election. The document’s anthropocentric tone reinforces the sense that man’s experience–not God’s revelation–has become the gravitational center of the reflection.

It’s the horizontal beam of the cross without the vertical.

It is the clash of the two sides of the Caesar coin.

And it was entrenched in post-conciliar documents well before Francis. The slide away from law and order, from Christ as King, has been slow and pernicious.

Perhaps most striking is the letter’s insistence on synodality as the Church’s defining mode of existence. The language of shared paths and friendly dialogue is presented not as a supplementary pastoral practice but as the ecclesial core itself. This represents not merely a change in style but a redefinition of the Church’s identity–from a divinely constituted, hierarchical, supernatural society to a horizontal, process-driven community whose unity is achieved by conversation rather than conversion. It makes irrelevant the blood of the martyrs that gave their lives to build the Church.

It is the seemingly virtuous stuff of a certain secret society.

As we’ve noted in our seemingly distinct (but not at all) political analyses time and time again, once the structure is softened and the definitions loosened, the institution becomes increasingly susceptible to the influence of whatever spirit or ideology happens to steer the conversation next. Most of us understand it as the cultural component of Communism. And while it goes much deeper than that, there is no question it is a better starting place than never starting at all.

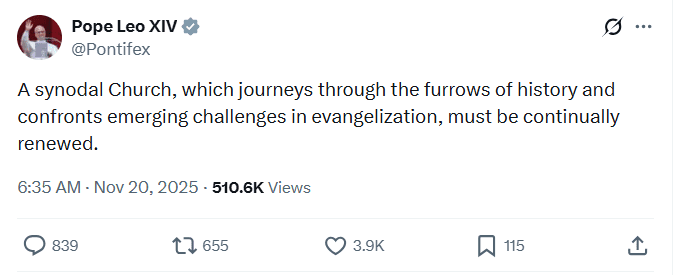

Here is a tweet from Leo just two weeks ago.

Imagine Christ saying that his teachings–his truth–must be consistently changed.

Did Christ preach a synodal Church to his apostles?

Or did he give them very specific commands?

As always, we can spot the Modernist trick very quickly if we simply apply the same language and spiritual radar we apply when we finally recognize the narcissistic lover’s modus operandi.

Another tell is that they sprinkle in some hard and fast Catholic truths for the everyday Catholic not paying attention. Their favorite topic in this vein is abortion. And they even manipulate Catholics with that because they use “pro-life” to support the ongoing invasion of civilized nations.

The devil intends to sound lovely, you know. He was the angel of light. Otherwise we wouldn’t follow him.

What on Earth Do We Do Then?

The narrative and the enmity are the same on both the political and the spiritual front. In our previous work exploring political propaganda, algorithms, and memory-holed history, we noted a recurring method that most everyone is able to recognize now in politics: suppress dissent, elevate consensus, redefine vocabulary, present the result as inevitable–and correct–based on the will of the mob. The same pattern appears here. The Church–or those controlling her public face–seems to signal that doctrine is secondary to unity; that dogma, law, and order are outdated; that any questioning of the new narrative is a relic of “rigid” traditionalism.

Perhaps we should recall St Paul’s words concerning the inevitable development of false teachings, in particular the notion of anathema:

I wonder that you are so soon removed from him that called you into the grace of Christ, unto another gospel. Which is not another, only there are some that trouble you, and would pervert the gospel of Christ. But though we, or an angel from heaven, preach a gospel to you besides that which we have preached to you, let him be anathema. As we said before, so now I say again: If any one preach to you a gospel, besides that which you have received, let him be anathema. 10 For do I now persuade men, or God? Or do I seek to please men? If I yet pleased men, I should not be the servant of Christ (Galatians 1.6-10).

What are we to think if, indeed, this letter, this In Unitate Fidei, like any other papal document in recent years (and decades), is not what it seems?

What if this is not a sincere call to rediscover ancient faith–but a blueprint for redefining Christianity, at least from the public point of view, from the top down?

What if it’s the ecclesial equivalent of a “phantom menace,” the kind of operation we’ve seen in modern politics and culture with such things as the Communist/Zionist dialectic and the Frankfurt School, just to name two, a hidden hand that operates under the cover of plausible deniability, manufactured unity, controlled narrative, and a slow dissolution of God-oriented law and order?

Keep the old words, mutate the meaning, then act as though nothing has changed while you’ve quietly undermined the foundations. Whether through politics or religion, the methodology is the same. If we stay silent, if we don’t test the spirits, the fog of consensus will continue to swallow us whole.

The mob is powerful. The mob once chose Barabbas.

So none of this is easy, I know.

We may or may not be at the point of no return as a society. But there is still time for the individual soul, for the souls of my family and friends, even for the souls of my enemies. May we recognize that a Church re-written is not a Church renewed–it is a Bride and Mother rejected. It is the calculated manifesto of a jilted and jealous enemy eagerly anticipating the number of those who will fall, an enemy anticipating the fulfillment of prophecies that warned this very thing would happen.